Introduction

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Academic Training (IAT) programme was introduced following recommendations within a 2005 report made by the Academic Careers Sub-Committee of Modernising Medical Careers and the UK Clinical Research Collaboration.1 This report highlighted the need for a more transparent academic career trajectory for trainees, with clear entry and exit points, and need for flexibility to be built into medical training to allow for research time. Now, more than fifteen years later, the NIHR IAT programme is well established, and arguably the best-recognised route for combining clinical and academic training in a given specialty. The protected research time provided by these posts is invaluable for pursuing scientific projects, acquiring any relevant technical or statistical skills, and for planning next steps, including applications for research funding.

In this article, our aim is to demystify the application and interview process for NIHR Academic Clinical Fellowships (ACFs) and Clinical Lectureships (CLs); we will also discuss how these positions fit within the clinical academic pathway. This article is an amalgamation of theoretical facts and our practical experience written in the context of Neurology training, but might also be of relevance and interest for other medical specialties. Whilst we have chosen to focus on NIHR posts in this article, as these are most commonly encountered and advertised, some academic centres also offer locally funded ACF and CL posts; details can often be found on the relevant university website.

Integrated Academic Training

The aim of IAT is to allow doctors to develop academic skills whilst pursuing clinical training in their respective specialty. This is available at all stages of clinical training (i.e., up until Consultant level), and includes the Academic Foundation Programme (AFP) for foundation year trainees, Academic Clinical Fellowships (ACF) for more junior specialty trainees (usually at the level of ST1 to ST3) and Clinical Lectureships (CL) for more senior specialty trainees after obtaining a PhD or equivalent qualification (usually at or above ST4 level).

Purpose, advantages, and disadvantages

Academic training provides trainees an opportunity to undertake their own research during supervised, dedicated, and protected time that may lead on to doctoral fellowships and eventually to senior clinical academic posts. During an ACF, the training is divided into 75% clinical and 25% research, while for the CL, the research component is increased, with time split such that 50% is clinical and 50% research.

For those interested in research at specialty training level, the ACF is the opportunity to look for. In our opinion, there are four main advantages. Firstly, without dedicated time, it becomes difficult to carry out substantial research, and the IAT therefore provides trainees with uninterrupted research time that is more likely to result in meaningful outputs (such as publications or presentations). Secondly, trainees can maintain their clinical skills in practice while doing research; this also provides a practical taster period for understanding clinical-academic responsibilities. Thirdly, the ACF research blocks can be an opportunity to rotate through different research groups; this immersive experience is really helpful when deciding where to be based for a future research degree. Finally, during the ACF period, trainees can prepare competitive applications for PhD fellowships.

Disadvantages are losing dedicated clinical training time and needing to attain competencies in a shorter period compared to non-academic peers. Although it depends on the deanery you are working in, this might also result in the loss of on-call benefits during academic block leading to reduction in overall take home pay. IAT is not for everyone, but it is a no brainer to take this opportunity if you are interested in exploring independent research.

General Principles

The commonest question is when to apply for the scheme. The best time for an ACF depends on individual career planning; posts are currently available at ST1 and ST3 grades, although this might change as Shape of Training is implemented. Earlier is perhaps better for those who are yet to decide about their preferences for becoming a clinical academic. However, it is possible to apply after the start of Specialty training. Both ACF and CL posts are competitive, often the interviews are cross specialty and often one post for Neurology and Obstetrics), so understandably, candidates require ample preparation to secure the post.

The ACF Process

Portfolio:

To outline preparation – the first task is to work on the portfolio. It will take time and is most effort-worthy. We would advise applicants to read through the up-to-date articles published by NIHR to understand person specification before applying.

Pre-interview:

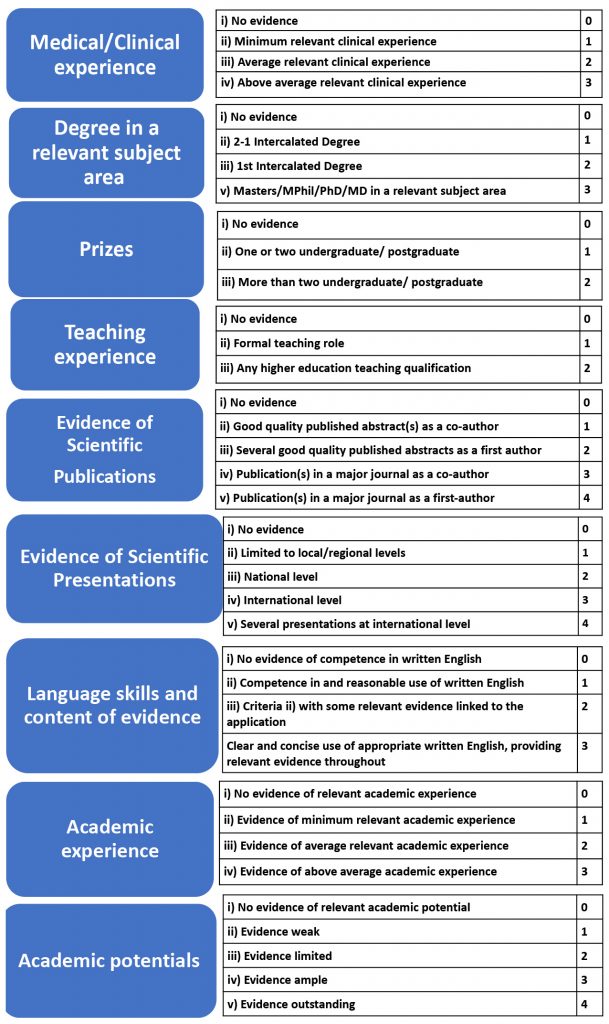

Candidates are shortlisted on their scores in 9 domains on a total score of 28. The table 1 shows the list of domains being assessed, and the maximum points that can be awarded. It is essential to work on these areas carefully once an ACF application is planned. For example – writing up a scientific paper is an important denominator, but it requires a good few months from planning to publication. Another way of gathering points is oral or poster presentation; this could be relatively easy but carries importance when scored. You do not need to score points in every domain, but your portfolio should reflect your academic potential and that’s why it requires accurate and timely planning.

The next point to consider in this process is finding a supervisor. Having an academic supervisor who can supervise your application and project is essential; this needs to be someone who can also can provide a reference. When you plan for your ACF application, you can contact experts in your field of interest. ACF interviews are regional; therefore, contacting potential supervisors from different regions is advisable to improve your chances of getting the job. Another point to consider is the centre/ institution offering the job. Different centres have reputations for different neurological subspecialties, so choosing the region wisely prior to training can be useful for the future.

Project

In the interview, the panellists are interested in your plans for your project. Although you do not need to know all the details, a neatly sketched out plan about the project is expected. Remember, if you are successful in your ACF, you have flexibility in what you can do during your research blocks; you do not necessarily have to commit all of your research time to the project or research group that you had in mind when you applied.

Finally, speaking to those who have been or are currently in the posts is always useful. Everyone has different perspectives to add to your planning. You can seek help for reviewing your portfolio or application and preparing for the interviews.

Table 1: The Shortlisting assessments for NIHR ACF post

Application

The application for round 1 starts from early October and it closes after 4 weeks. It requires a good few hours to write up the application, therefore, starting the application well ahead of the closing date is recommended. The Oriel application system has been used for the application to date. Along with declarations, personal, educational and employment related information in the first few pages, there are questions about publications and presentations, teaching and clinical experience, achievements outside medicine, suitability and commitment to the speciality, management and leadership skills and research related questions. There are free text boxes allowing 100 -300 words, which varies depending on the importance of the question.

Table 2: Top Tips for ACF Application

Interview preparation

The long-listing and shortlisting process usually takes at least a couple of weeks before candidates are invited for interview. There is detailed guidance about the interview questions and marking scheme on the NIHR website and reviewing the website information is recommended.

Pre-COVID, interviews were face-to-face, and a single panel interview used to be conducted for 40-45 minutes. In 2020, a 30-minute interview was conducted virtually in MS teams. The fundamental interview preparation is similar i.e., formal attire, reach/ log in on time, keeping passport and portfolio at hand). The panel member includes the lead of the ACF training programme (or representative), additional representatives from the relevant clinical academic community, a lay representative and a recruitment officer.

Dataset interpretation

The 1st part of the interview assesses candidate’s ability to interpret a generic dataset, scientific and lay audience. For the face-to-face interviews, the dataset is released 10 minutes before the interview and for virtual interviews, the scientific paper/dataset is sent to the candidate’s email 72 hours prior to the interview. For basic data interpretation, the Cochrane handbook or Cochrane online interactive courses are useful. The positive indicators as advised by NIHR interview guidelines include clear communication; ability to summarise succinctly; discussion of relevant controls and confounders; discussion of statistical analysis.2 For the lay summary, communication in plain English is expected. You are strongly advised to avoid complex sentences and jargon, and the significance of the data should be conveyed in simple language.

The next part of the interview encompasses questions related to academic achievements, knowledge about the planned project, institution and lab facilities available, experience of previous research, discussing a scientific article outside of immediate area of expertise and tactics for balancing both clinical and academic responsibilities.

Table 3: Top Tips for ACF Interview

Clinical benchmarking

As previously mentioned, applications and interviews are regional, therefore, candidates can apply for Neurology ACF posts in different regions and interviews are conducted on different dates. If a candidate is successful at the ACF interview and if they do not hold an NTN or DRN in that respective specialty at the ST level advertised, they will need to attend clinical benchmarking. This refers to the process of ACF applicants obtaining the threshold of appointability at the national clinical interviews for the specialty and level of ACF post.2 If a candidate is successful in ACF interview but fails to reach the ‘threshold of appointability’ they will not be eligible to be appointed as ACF in that recruitment round.

Successful or not?

If you secured the post and sailed through the clinical benchmarking, that’s a great achievement. If not, there is always a next time. Interview experience itself is a learning process. All you need is to plan, prepare and practice for the next session.

The CL process

Before you apply

The NIHR CL usually lasts for 4 years (it can be less, if you are closer to completing your training), and allows 50% of that time to be protected for research. More recently, CL posts have aligned with NIHR “research priority themes”; the relevant calls for Neurology are usually in Platform Science and Bioinformatics, and Dementia, but theoretically could include Therapeutics or Clinical Pharmacology, and Older People and Complex Health Needs.

As explained below in the “What happens next?” section, this is an excellent opportunity to start preparing for intermediate fellowship (and equivalent) applications. Whilst many people choose to stay in the research group where they completed their PhD, this can be a chance to explore a different aspect of your research field; remember, when you make your intermediate fellowship application, you will need to demonstrate that you are working on something novel and unique, and that sets your research trajectory for at least the next five years.

In completing a PhD, you will be aware of the limitations within your research field, and a CL could provide time for you to start carving out a new niche for yourself, perhaps in an area that has been understudied previously. For this reason, it is essential to learn more about the institution hosting the CL and the training opportunities it can provide. As well as technical expertise, the presence of more senior clinician scientists who can provide mentorship and other career-related advice can be really important. Of course, it is also important to think carefully about the research group you will join during your CL, and if you are looking beyond your PhD group, reach out to potential supervisors. Most senior academics are happy to speak to motivated clinicians interested in research – and if you don’t get a reply, you have lost nothing.

In terms of eligibility, you will be expected to have at least submitted your PhD at the time of your application (you might be asked to provide evidence of this) and you can only take up a CL post once your PhD has been fully awarded, so bear this in mind when making your application. It is also worth reviewing the person specification which accompanies the application (a generic version can be found on the NIHR website); this sometimes includes subspecialty requirements (e.g. expertise in a particular disease), as well as skills in more general areas (such as teaching, leadership and management).

Application form

The application form is similar to the ACF form, but slightly longer. At the time of writing, CL applications were managed via the Oriel system. As with all Oriel applications, it is a good idea to save a PDF of the blank form, and then draft your answers in MS Word (or equivalent) before copying and pasting the final version into Oriel once you are ready to submit.

Previous questions have included those about experience in and commitment to your specialty; experience of teaching, clinical governance (including audit and quality improvement), leadership and management; your PhD research; your academic achievements to date (including relevant outputs such as presentations and publications) and evidence of your commitment to an academic career. Example questions that frequently appear on the application form can be found on the NIHR CL webpages (although the word limits are not included).

Interview

As with any interview, there are questions that are easily anticipated. Be prepared to summarise your career to date, and what you worked on during your PhD. You should be able to explain why you have chosen your specialty and sub-specialty, your area of research, and why you want to be an academic clinician. You will be expected to be well versed in the academic career trajectory from CL to Senior Clinician Scientist (Professor and Consultant Neurologist). As well as questions about your PhD research and the work you propose to do during a CL, should you be successful, you might be asked questions about the personal qualities you have that lend yourself to an academic career, including those relating to resilience in the face of failure, work-life balance, and juggling your clinical and research commitments. You might additionally be asked about teaching, leadership and management experience.

Table 4: Top Tips for CL Application and Interview

What happens next?

Both ACF and CL positions can be stepping-stones to future positions, and particularly those that require independent grant funding. In the case of the ACF, which is traditionally (but not always) a pre-doctoral position, the next step is a PhD. In most cases, potential PhD applicants will need to apply for fellowship funding, in the form of Clinical Research Fellowships and equivalent awards. In most cases, these awards cover the applicant’s salary in full, and also provide some funds for research consumables. These awards are provided by national bodies such as the Medical Research Council (MRC), Wellcome Trust, the NIHR and Association of British Neurologists (ABN), as well as some disease-specific charities, and the application process can be very competitive. The research time embedded within an ACF can be used to generate pilot data for these PhD funding applications, as well as time to write and submit the application(s). For those unsure about the type of research to pursue, the ACF can be an opportunity to try different groups and work with different potential supervisors. Whilst it is possible to apply for PhD funding without an ACF and whilst working full time clinically, the time provided by ACF allows you to make a more competitive fellowship application, and this can make all the difference.

In a similar way to the ACF, the CL, as a post-doctoral equivalent to the ACF, can be seen as a stepping-stone towards intermediate fellowships and equivalent applications. Intermediate fellowships are a real bottleneck in the academic career pathway; they are the final stage in the transition to research independence, and the application process is both lengthy and extremely competitive. Having time to generate pilot data, define your research area and trajectory (which might be in a different direction to your PhD supervisor or group) and acquire any additional technical skills (if relevant) is crucial for these applications; unlike PhD funding, it is very difficult (and some would say impossible) to do all this whilst working clinically full time. Stand-alone grants that provide consumable costs during CLs (for example, the Academy of Medical Sciences Starter Grants for Clinical Lecturers), allow you to put together a small funding application as the lead applicant, which can be an informative experience (particularly if you are unfamiliar with the administrative processes of the university relevant to grant applications). The CLs also allows you to keep generating research outputs, in the form of presentations and publications, including those that were generated but not finished during your PhD. The CL therefore provides a unique opportunity to fully prepare for what is arguably the most competitive funding application for an early career researcher.

Conclusion

We hope that this article has achieved its aim of demystifying the IAT programme for trainees, and highlighted its many advantages, particularly for those interested in research. It may feel daunting in the beginning, therefore we emphasise understanding the whole process first and then preparing adequately for the programme. Remember, sometimes initiating a new step may feel equivalent to moving a mountain, but eventually, with adequate planning and calculative thinking, we reach the doorstep of success. It is important to say that ACFs and CLs are not the only path to becoming a successful clinical academic, and they are not the best option for everyone – so if you are not successful in obtaining one of these posts, do not despair. Explore all the options including university sponsored fellowships and prepare for the interview adopting a structured approach.

Good luck!