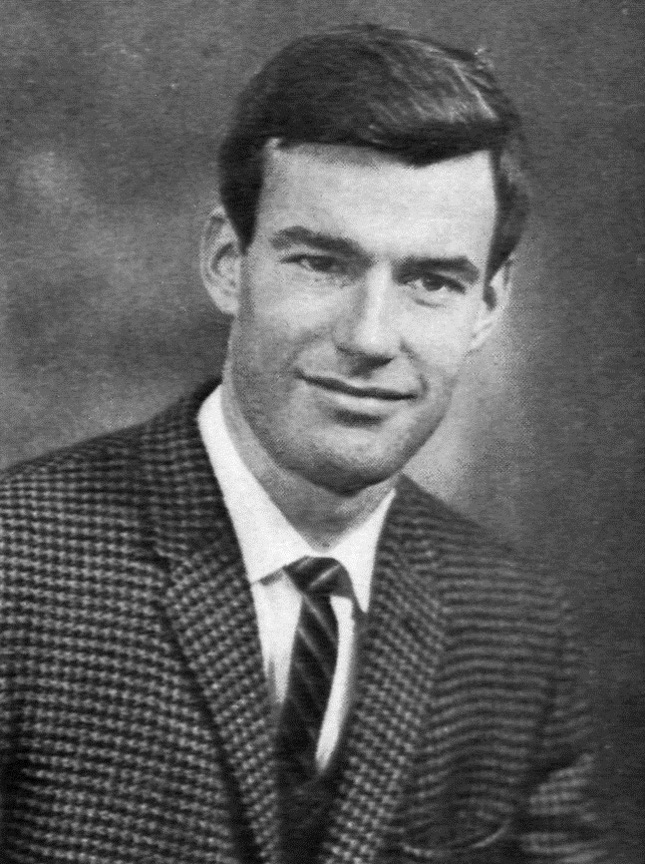

With a career in medicine and academia spanning over five decades, Professor John Pollard has devoted much of his life to the development of Australian neurology. His fascinating career has been punctuated with numerous achievements, particularly in the field of inflammatory neuropathies. Now at the age of 79, he continues to work as an active Consultant Neurologist and Co-Director at Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre, seeing and treating patients.

In May 2019 we caught up with Professor Pollard after a busy afternoon list of clinics, in his seemingly ordinary consulting room set in the middle of the leafy Sydney suburb of Camperdown. As two medical students from London universities, we were visiting Sydney to learn about the way that clinical neurology is practised in a different environment from home. Part of this experience afforded us the opportunity to interview Professor Pollard. He recounted stories from his illustrious life, from his time as a young medical student and junior Doctor, to his career as a practising clinician and academic. A story that spans over half a century, Professor Pollard’s experience reflects the changing practice of neurology in Australia, and holds many inspiring elements for future generations of aspiring researchers and clinicians.

Beginning of a passion

Since an early age Professor Pollard harboured an interest in the natural sciences. This eventually led him to the University of Sydney, where he started his studies as a medical student. He had his first memorable encounter with neuroscience that was to influence the rest of his career.

‘After fourth year of medical school I decided to take a year off and do a science degree. In those days the chemical neurotransmission in the CNS was largely unknown. At that point Feldberg and Gaddum1 had produced evidence for acetylcholine as a neurotransmitter in the autonomic nervous system, and Eccles et al.2 had shown its involvement in the synapses between the anterior horn cell and Renshaw cells of the spinal cord. However the neurotransmitter for the lateral geniculate bodies and optic nerves was not known.’

The project I took on was to take lateral geniculate bodies in optic nerves of sheep, and see if we could extract them to find pharmacologically active materials. This involved going out into the countryside, to the abattoirs, and I’d spent the most horrendous day in that rather unpleasant situation – dissecting the optic nerve and lateral geniculate from sheep that had been recently slaughtered. We had to get the nerves out within forty seconds and have them in liquid nitrogen to stop the autolytic processes from destroying what we were looking for. We had to dissect out around fifty nerves, and it was very hard work.

‘What this experience taught me was great reverence for every line of a textbook. I realised how much hard work went into every line, so in my medical studies it gave me a great respect for the knowledge within those books. It was also wonderful, I think, to take some time off from the rigours of clinical slog and book learning. It gave me time to read poetry and novels, and it gave me time to go to courses on the philosophy of science.’

Broadening horizons

After graduating from the University of Sydney Medical School in 1966 and completing his houseman years, Professor Pollard embarked on specialty training to become a Neurologist. His training as a Neurology Registrar eventually led him to travel abroad to the United Kingdom, where he worked and trained at the Royal Free Hospital and the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, commonly known as Queen Square.

‘Now, at Queen Square, there were many wonderful teachers, and some leading world figures, like PK Thomas in peripheral nerve disease, and John Newsom-Davies in diseases of the neuromuscular junction, and Ian McDonald who was the world leader in the field of multiple sclerosis. Apart from these wonderful teachers and outstanding clinical scientists there were many interesting and delightfully eccentric people.’

‘I first met John Newsom-Davies who was a visiting Neurologist at the Royal Free and at Queen Square. John in those days was studying the neurophysiology of the neuromuscular junction. Now they were the days when the underlying cause of myasthenia was uncertain – understanding that mechanism was John’s major interest.’

‘But in 1973, DM Fambrough et al published a paper3 showing that the fundamental abnormality in myasthenia gravis was a lack of bungarotoxin binding sites – in other words acetylcholine receptors in the post synaptic membrane. In 1976, Lindstrom et al,4 from the United States, demonstrated that in fact in 95-100% of patients with myasthenia there were raised levels of antibodies to the acetyl choline receptor, suggesting this was an antibody mediated disease. John Newsom-Davies, in 1977, the year after I returned from London, treated three severely weak myasthenic patients with plasmapheresis and demonstrated this miraculous recovery of strength, and that was the study which convinced Neurologists of my generation that this really was an antibody mediated autoimmune disease’

Pioneering therapies

His encounters with these eminent and eccentric figures in the UK inspired Professor Pollard’s own clinical and academic work. On the back of these breakthroughs, he would go on to develop therapies for the many patients suffering from these debilitating diseases.

Plasmapheresis

‘When I came back to Australia I began to look after patients with multiple sclerosis, autoimmune neuropathies, and myasthenia gravis. I was aghast at the number of myasthenic patients disabled with chronic disease. The treatments then available were anticholinesterases, thymectomy, and corticosteroids, and many suffered the ravages of long-term steroids. After multiple admissions to intensive care units requiring tracheostomies, many of them were institutionalised.’

‘I rang John Newsom-Davies about this, and he told me about these results from the plasmapheresis, and I applied that to some of these patients. I found, as he did, that in the short term it was miraculous in its effect.‘

Then I introduced an immunotherapy in the form of azathioprine and decremental doses of steroids. Patients who had been institutionalised did so well that they were able to go out and live a free and normal life. That was a most gratifying experience.

Professor Pollard was impressed by the degree to which his patients responded to these therapies, and his thoughts turned to their potential use in other neuroinflammatory diseases.

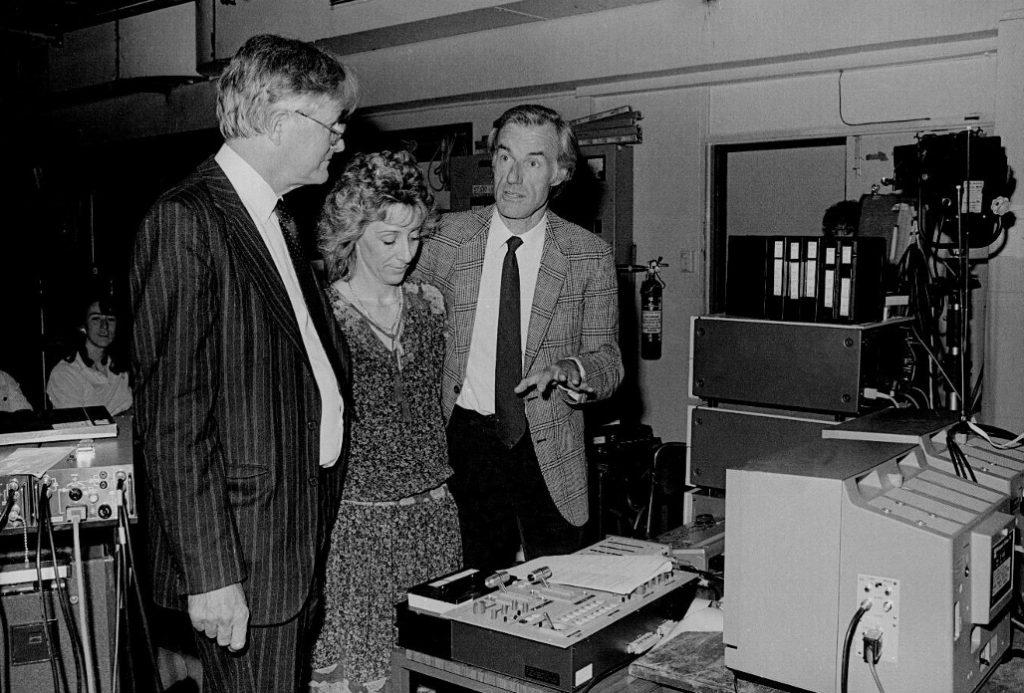

‘I thought about applying plasmapheresis [as John Newsom-Davies had for myasthenic patients] to the immune neuropathy situation. I set up an animal model of plasmapheresis in a rabbit model of chronic immune neuropathy. We were able to demonstrate that in rabbits with severe paralysis and high levels of anti-myelin IgG, their disease stabilised and improved with plasma exchange.’

‘I then introduced plasma exchange as treatment to patients with Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (CIDP) in Australia, and some patients who hadn’t responded to any other treatment, in those days which was steroid, did remarkably well. One of the most satisfying experiences in my life was seeing people who had been confined to a wheelchair with severe paralysis, recover their mobility and return to a normal life.’

Intravenous immunoglobulin

It became apparent that these new immunotherapies could provide much more effective treatment for a number of debilitating diseases that clearly had an autoimmune basis. But with these new opportunities came new challenges.

‘Later on, after 1985, the Dutch published the fact that CIDP, and later Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), would respond to intravenous immunoglobulin(IVIg); a much safer treatment than steroid and immune suppression and simpler to administer than plasmapheresis. When I attempted to obtain intravenous immunoglobulin for my patients, I discovered that this precious resource was strictly controlled; for the haematologists for use in the patients with Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP), and the immunology patients with immunoglobulin subclass deficiency. It was impossible to get for neurological use.’

‘I travelled around Australia attending meetings of Haematology and Immunology, describing how effective this therapy was for people with chronic neuropathies who were severely paralysed, showing videos I had taken of severely weak people recovering their strength and mobility.’

I used to go and visit sporting clubs – if I had a patient in an area surrounded by a sporting club, I would go out and ask those fit young people to donate blood to the blood banks so that we could extract immunoglobulin for the patient from their area.

‘Eventually a National Body was established to control the use of IVIg for therapeutic purposes. This body decided that IVIg should be given only to those conditions for which class 1 evidence for efficacy from controlled clinical trials was available and fortunately there was plentiful such evidence in the neurological literature. IVIg then became available in Australia for the treatment of autoimmune neuropathies. A contemporary of mine from Queen Square in the 1970s, now Professor Richard Hughes from Guys Hospital, made a major contribution to this literature, particularly in the form of influential Cochrane reviews.’

Today, immunotherapy, plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin have become mainstays in the treatment of immune-mediated neurological conditions. Professor Pollard’s contribution in this field improved the lives of many patients who suffered from these debilitating conditions, both in Australia and around the world.

The Neurologist

After working as a Neurologist over the span of five decades, Professor Pollard continues to be inspired and humbled by his patient’s experiences, reminding him of why he chose to become a Neurologist all those years ago.

‘I think of a young lady that I saw in clinic down in South Sydney, who was only nineteen. She came to me complaining that she had no memory.’

‘I said to her “really, what do you forget, where you lose your keys? Or do you forget what you’ve come down the shops to buy?’

‘But she replied “no, Doctor, a year ago I had a baby, and I can’t remember giving birth to that baby’, and I thought “goodness – this is significant memory loss.’

‘Her neurological examination was normal, and she was bright and lively. But I thought of the things that might affect memory in a young woman, and as I talked to her it was obvious that she was having mild, but multiple absences. She obviously had mild partial complex seizures, and she was wiping the memory circuits in her temporal lobe.’

‘When we put her on sodium valproate, these eventually ceased, and her memory returned over months – it was life changing for her.’

In these days when computers are playing such a role in medicine, we still need the importance of history and examination because the computers do not give us the whole answer. There are often clues in the history and examination.

The future

‘I think that people planning to come into medicine should recognise it is a wonderful, interesting, and exciting field. You should enjoy it. It is a great privilege helping people, and contributing in small measures to their wellbeing.’

‘I think contributing to medicine means keeping up to date, at least in your field with scientific advances. I would suggest that every medical practitioner should do their best to contribute in some small measure to science and science advancement at least in their field. Every small addition to knowledge can give satisfaction.’

‘Participating in the international research community and attending national and international conferences facilitates meeting colleagues who share your ideas and interests. Many of these colleagues will become collaborators and wonderful friends and this is one of the great privileges of working in the sciences and clinical sciences.’

References

- Feldberg W, Gaddum JH. The chemical transmitter at synapses in a sympathetic ganglion. J Physiol. 1934;81(3):305-319. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1934.sp003137

- Eccles JC. Excitatory and inhibitory synaptic action. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1959;81(2):247-264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1959.tb49312.x

- Fambrough DM, Drachman DB, Satyamurti S. Neuromuscular junction in myasthenia gravis: Decreased acetylcholine receptors. Science (80- ). 1973;182(4109):293-295. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.182.4109.293

- Lindstrom JM, Seybold ME, Lennon VA, Whittingham S, Duane DD. Antibody to acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis: Prevalence, clinical correlates, and diagnostic value. Neurology. 1976;26(11):1054-1059. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.26.11.1054