Headache Series – Introduction

Anish Bahra MB, ChB, FRCP, MD, is the Editor of ACNR’s Headache Series and Consultant Neurologist at Barts Health and the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (NHNN), UK. Her specialist interest is in primary and secondary headache disorders having completed her original research in Cluster headache. She runs a tertiary Headache service at the NHNN and a neurostimulation MDT at Barts Health.

The Headache series aims to address topical issues in headache. Despite being the most common neurological disorder, management remains challenging. This series was introduced by the topic of vestibular migraine, in which it is often not the headache but the neurological symptoms which confer the brunt of the disability. Forthcoming editions include the association with sex hormones, well known but less well understood and the advent of the new anti-CGRP monoclonal antibody treatments.

Migraine in perimenopausal women

Abstract

There is an unmet need for effective diagnosis and management of migraine in perimenopausal women. Menstrual cycle hormone disruption during perimenopause is associated with an increase in migraine and menstrual migraine prevalence, together with other more commonly recognised menopause symptoms. Women of perimenopause age, i.e., early 40s to mid 50s, should routinely be asked about migraine and menopause symptoms, and provided with effective tools for management as appropriate. Simple diaries can be used to identify the frequency and duration of attacks, as well as the relationship to menstruation at outset, and to monitor response to treatment. While there is no evidence to support prescription of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) solely for management of migraine, it is the most commonly used treatment for menopause symptoms. As some types and regimens of HRT can negatively affect migraine, the general recommendation is to use transdermal oestrogen and continuous progestogen regimens where possible. In contrast to contraceptive synthetic oestrogens, physiological doses of natural oestrogen can be used by women with migraine aura. Most women, particularly those with a history of menstrual migraine, can be reassured that the natural history of migraine is to improve with increasing years post menopause.

Introduction

Perimenopause typically begins when a woman is in her early to mid-40s. It is the stage of hormonal transition from previously regular, predictable menstrual cycles that encompasses dynamic changes with the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, culminating in menopause. Menopause transition is marked by disrupted menstrual cycles as hormone production from the ovarian follicles becomes erratic, with high estradiol levels and low luteal phase progesterone [1]. This results in symptoms of irregular bleeding, hot flushes, night sweats, mood changes and sleep disturbance that are characteristic of this stage of life. Natural menopause is defined as having occurred after 12 months of amenorrhoea following the last menstrual period. In the UK, average age at natural menopause is 51 years but ranges between 45 and 55 years. Although ovulation ceases at menopause, ovarian hormonal activity persists for several years post menopause, as reflected by a gradual decline in symptoms.

The prevalence of migraine, and menstrual migraine in particular, increases during the menopause transition and improves with increasing time following physiological menopause, mirroring changes in the hormone environment [2].

This paper discusses the clinical management of migraine during perimenopause and the role of HRT.

Epidemiology

Migraine is an underreported complaint in perimenopausal women and is both underdiagnosed and undertreated in this population. In a recent study of women attending a London menopause clinic, 41% were diagnosed with migraine, of whom 27% experienced attacks of migraine with aura [3]. Using the validated Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), migraine associated disability was very severe (HIT-6 60+) or substantial (HIT-6 ≥56≤59) in 48% of migraineurs. Despite this high level of disability, most women were treating attacks with paracetamol alone, or had been prescribed medication containing codeine, which is inappropriate for migraine management [4].

In contrast to the benefits of physiological menopause, hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy is associated with a higher prevalence of migraine compared to women who have not had surgery [5].

Menstrual migraine

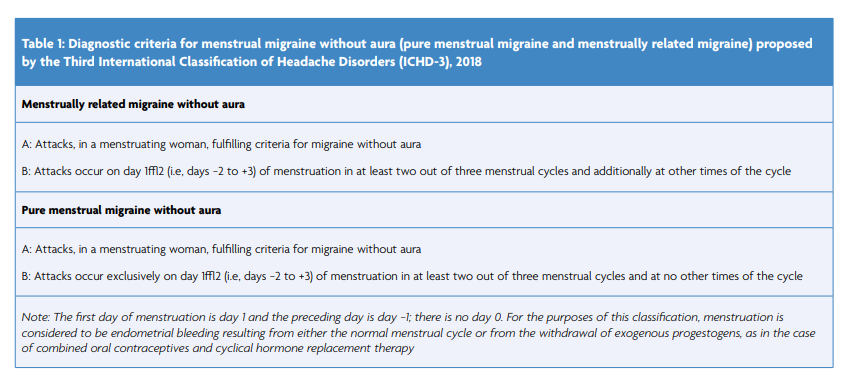

During perimenopause some women report regular perimenstrual attacks of migraine. As shown in Table 1, the International Headache Society defines menstrual migraine as migraine attacks that occur within a 5-day window starting two days before the first day of menstruation, through to the third day of bleeding [6]. Solely perimenstrual attacks (pure menstrual migraine) are uncommon and most women also experience attacks at other times of the cycle (menstrually related migraine).

In women diagnosed with menstrually related migraine, perimenstrual attacks are more severe, more disabling, last longer and are less responsive to symptomatic medication compared with attacks at other times of the cycle [7]. These perimenstrual attacks are typically without aura, even in women who have attacks with aura at other times of the cycle. To confirm a genuine hormonal relationship, a diagnosis of ‘menstrual migraine’ should only be made if the association between perimenstrual attacks and menstruation is greater than chance [7].

A diagnosis of menstrual migraine is aided by use of simple diaries with pictorial representation of migraine attacks and menstruation on each day of the month, as show in Figure 1. This diary confirms the diagnosis of menstrually related migraine, in which menstruation is irregular but associated with regular perimenstrual attacks, that are of longer duration compared to attacks at other time of the cycle.

Pathophysiology

Studies have not identified any consistent biochemical or hormonal abnormalities in women with perimenopausal migraine, compared with control groups. It is likely that a number of independent mechanisms act perimenstrually, which can occur discretely or in combination. One established mechanism for menstrual attacks of migraine is the natural fall in oestrogen during the late luteal phase of the normal menstrual cycle [7]. A likely reason why this is a relevant factor during perimenopause is the significantly higher perimenstrual estrogen levels in perimenopausal compared to premenopausal women [8].

High estrogen levels during perimenopause also increase the risk of menorrhagia, [9] which is accompanied by an increase in prostaglandins and prostaglandin metabolites in the systemic circulation [10]. Infusion of prostaglandins has been shown to induce migraine like attacks, so increased prostaglandin release during perimenopause is a likely additional risk factor for migraine [11].

Progesterone is metabolised to allopregnanolone, a potent positive allosteric modulator of GABA-A receptors, inhibiting cortical excitability [12]. Thus, the increase in anovulatory cycles and consequent low luteal phase progesterone levels that characterise perimenopause may further increase the risk of migraine at this time.

Management

Migraine must first be diagnosed before it can be optimally managed. Given the association between migraine and perimenopausal vasomotor symptoms, women seeking help for menopause should be asked about migraine symptoms and vice versa [13].

Lifestyle

Lifestyle changes, including sleep hygiene, regular exercise, regular meals, and maintaining a healthy weight benefit both migraine and menopause symptoms.

Management of acute attacks

Symptomatic treatment should be provided in accordance with local or national guidelines [4, 14]. Diaries can be used to assess the frequency of medication as regular use more than 2-3 days a week risks medication overuse headache.

Prophylaxis

Migraine prophylaxis should be considered if migraine attacks are frequent and/or symptomatic treatment does not provide effective attack control. Unless a diagnosis of menstrual migraine is made, standard migraine prophylaxis is indicated, in accordance with local or national guidelines [4, 14].

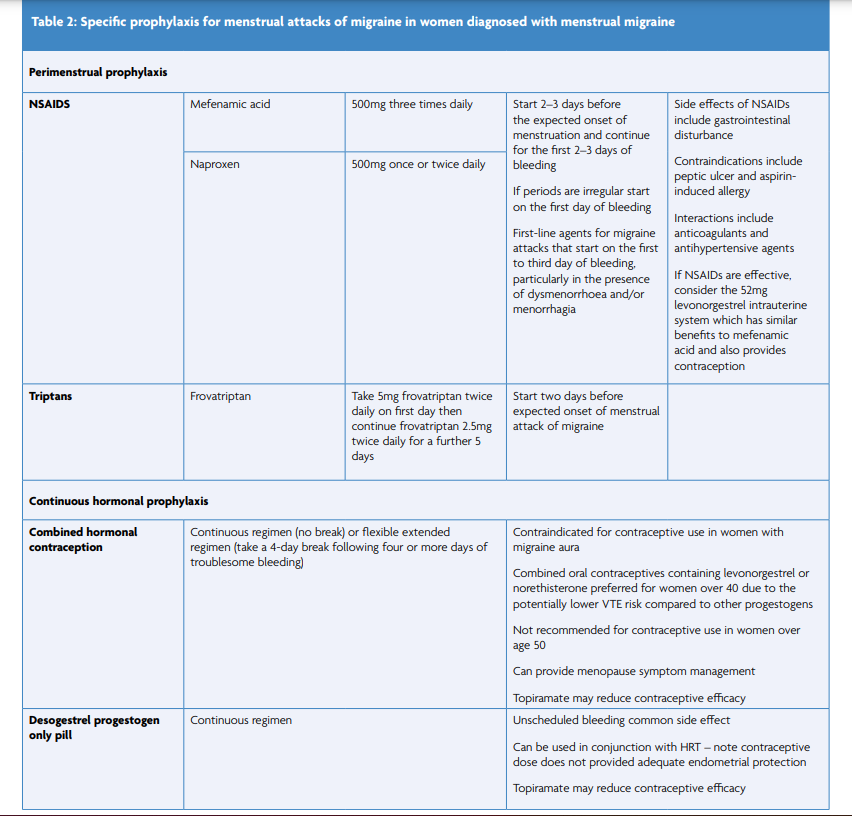

Women diagnosed with menstrual migraine have the option to try specific targeted evidence-based perimenstrual or continuous prophylaxis, including contraceptive hormonal regimens, as shown in Table 2. Data regarding the effects of other contraceptive methods on migraine are limited. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate inhibits ovulation and the menstrual cycle and so should be effective on potential mechanisms for perimenstrual exacerbation of headache [15]. The progestogen-only implant inhibits ovulation but does not reliably inhibit ovarian activity. Although some women using the implant experience fewer migraine attacks, particularly those who become amenorrhoeic, this method more often results in fluctuating estrogen levels, unscheduled bleeding, and exacerbation of migraine. To date, there are no data regarding the effect of the drospirenone progestogen-only pill on migraine.

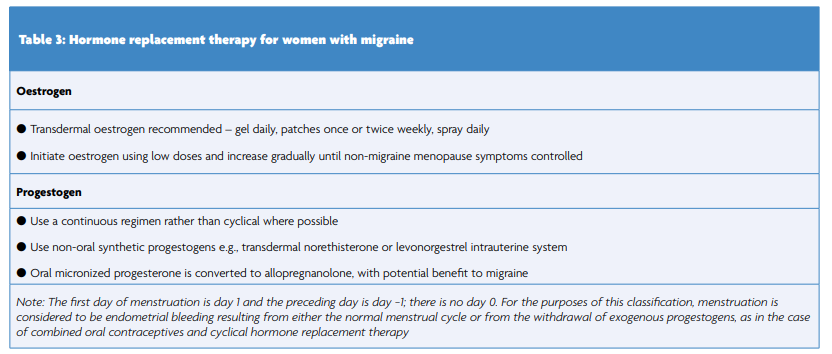

Hormone replacement therapy

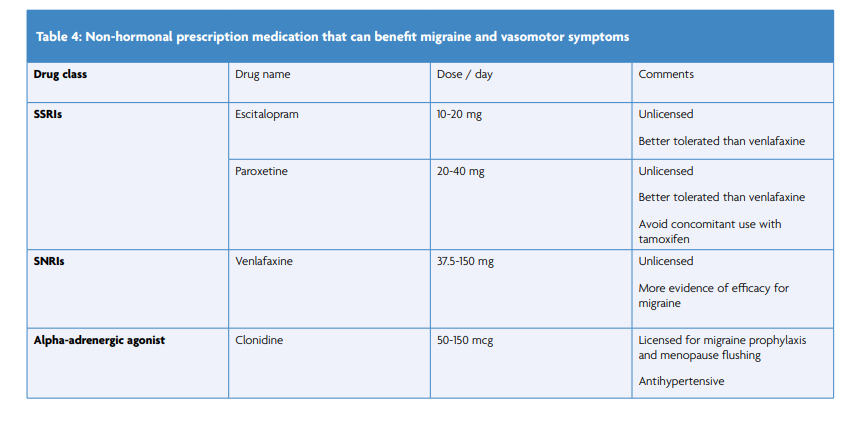

Hormone replacement is indicated for management of typical perimenopausal symptoms and not specifically for migraine management. It should be prescribed in accordance with local or national guidelines [16, 17]. However, some types and regimen of HRT can negatively affect migraine and inappropriate use of HRT during early perimenopause can augment hormone fluctuations, further exacerbating migraine. To maximise benefit to migraine, the aim is to maintain stable hormone levels where possible (Table 3). If migraine persists once other menopause symptoms are controlled, review non-hormonal triggers and consider non-hormonal management strategies (Table 4).

In contrast to use of contraceptive synthetic oestrogens women with migraine aura can use HRT. Transdermal oestrogen should be prescribed where possible as it does not adversely affect risk of ischaemic stroke [18]. If a woman develops new onset confirmed migraine aura when starting HRT, switch to transdermal if not already prescribed, reduce the oestrogen dose, or consider non-hormonal options.

Conclusion

Migraine is adversely affected by hormone changes during the menopause transition. Healthcare providers treating perimenopausal women should specifically ask about migraine symptoms, diagnosing and treating accordingly. Where HRT is indicated, continuous regimens with transdermal oestrogen are least likely to adversely affect migraine and, by stabilising hormone levels, may benefit migraine.

References

- Hale GE, Hughes CL, Burger HG, Robertson DM, Fraser IS. Atypical estradiol secretion and ovulation patterns caused by luteal out-of-phase (LOOP) events underlying irregular ovulatory menstrual cycles in the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2009;16:50-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31817ee0c2

- Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR, Juang KD, Wang PH. Migraine prevalence during menopausal transition. Headache. 2003;43:470-8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03092.x

- MacGregor A, Pundir J. Headache in women attending a menopause clinic: an unmet need? Cephalalgia. 2021;4:105. https://doi.org/10.1177/03331024211034005

- BASH. National Headache Management System for Adults. British Association for the Study of Headache; 2019. Available at: https://www.bash.org.uk/downloads/guidelines2019/01_BASHNationalHeadache_Management_SystemforAdults_2019_guideline_versi.pdf (Accessed 9th July 2022)

- MacGregor EA. Perimenopausal migraine in women with vasomotor symptoms. Maturitas. 2012;71:79-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.11.001

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417738202

- Vetvik K, MacGregor EA. Menstrual migraine: a distinct disorder needing greater recognition. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:304-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30482-8

- Santoro N, Brown JR, Adel T, Skurnick JH. Characterization of reproductive hormonal dynamics in the perimenopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1495-501. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.81.4.1495

- Moen MH, Kahn H, Bjerve KS, Halvorsen TB. Menometrorrhagia in the perimenopause is associated with increased serum estradiol. Maturitas. 2004;47:151-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-5122(03)00250-0

- Tsang BK, Domingo MT, Spence JE, Garner PR, Dudley DK, Oxorn H. Endometrial prostaglandins and menorrhagia: influence of a prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor in vivo. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1987;65:2081-4. https://doi.org/10.1139/y87-326

- Antonova M, Wienecke T, Olesen J, Ashina M. Prostaglandin E(2) induces immediate migraine-like attack in migraine patients without aura. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:822-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102412451360

- Gonzalez SL, Meyer L, Raggio MC, Taleb O, Coronel MF, Patte-Mensah C, et al. Allopregnanolone and Progesterone in Experimental Neuropathic Pain: Former and New Insights with a Translational Perspective. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2019;39:523-37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-018-0618-1

- Maleki N, Cheng YC, Tu Y, Locascio JJ. Longitudinal course of vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal migraineurs. Ann Neurol. 2019;85:865-74. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25476

- The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guideline. Headaches in over 12s: diagnosis and management. 2012 Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg150 (Accessed 9th July 2022)

- MacGregor EA. Contraception and headache. Headache. 2013;53:247-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12035

- Hamoda H, Panay N, Pedder H, Arya R, Savvas M, on behalf of the British Menopause Society and Women’s Health Concern. The British Menopause Society and Women’s Health Concern 2020recommendations on hormone replacement therapy in menopausal women. Post Reprod Health. 2020;26:181-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053369120957514

- The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guideline. Menopause: Diagnosis and Management. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23 (Accessed 9th July 2022)

- Canonico M, Carcaillon L, Plu-Bureau G, Oger E, Singh-Manoux A, Tubert-Bitter P, et al. Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Stroke: Impact of the Route of Estrogen Administration and Type of Progestogen. Stroke. 2016;47:1734-41 https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013052