The National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines aim to improve the quality of healthcare. They provide evidence based recommendations for the treatment and care of patients with specific disorders. The guidelines can be used to develop standards of care and provide a useful tool for auditing clinical practice. In 2003, NICE first published guidelines for the management of head injured patients (Clinical Guideline 4) [1]. In September, 2007, an extensive update including amendments to existing advice and new recommendations was published (CG 56) [2]. The guidelines and the update were compiled by a large panel of interested parties after an exhaustive review of the available literature. This paper aims to summarise the features of head injury care as recommended by the guidelines.

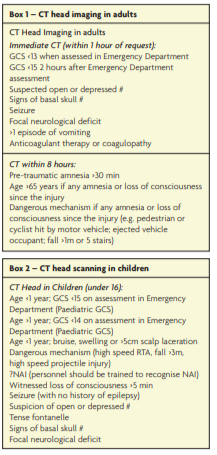

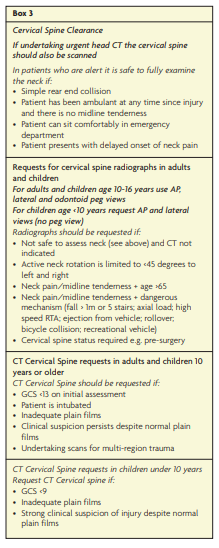

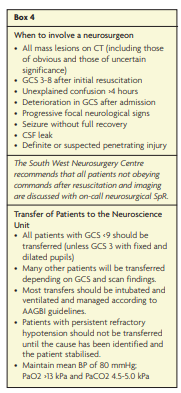

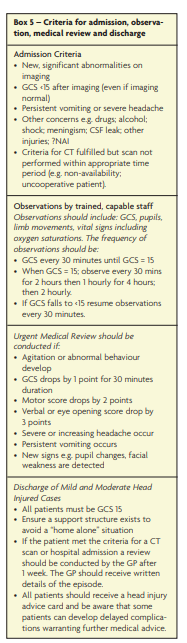

The objective of care for head injured patients is to ensure timely recognition and treatment of significant injuries in an appropriate healthcare setting. The NICE guidelines have led to a shift in management from an “admit and observe” strategy to a “diagnose and decide” approach. The guidelines provide advice on pre-hospital management, assessment in the emergency department, investigation for brain and cervical spine injuries (see Boxes 1, 2 and 3), recommendations for referral and transfer to a neurosurgical unit (see Box 4) and guidelines regarding the admission, care and discharge of brain injured patients (see Box 5). The key features of the guidelines include the following:

- Head injured patients should be transported to a facility with the resources to resuscitate, investigate and provide initial management of multiple injuries. The initial assessment and management should follow the principles of the Advance Trauma Life Support system.

For patients with a GCS 3-8 the paramedic crew should make a stand-by call to ensure that appropriate personnel are available to treat the patient at the receiving hospital.

- The spine should be immobilised for all patients with GCS < 15, any history of neck pain or tenderness, any extremity paraesthesia, any focal neurological deficit or any other suspicion of a cervical spine injury. Immobilisation should remain in place until a full assessment has been conducted (Box 3).

- Immediate clinical assessment should be conducted in the Emergency Department for all patients with a GCS <15. All patients with a GCS of 15 should be assessed by trained staff within 15 minutes of arrival.

- The admitting team should be competent to assess, observe, investigate and transfer patients. If the patient has sustained polytrauma, admission should be under the care of the team who are dealing with the most severe and urgent clinical problem.

- All serious head injuries (GCS 3-8) should be transferred to a neuroscience unit. If logistics prevent transfer, neurosurgeons should assist and advise.

- Patients and carers should be aware of potential long-term symptoms and disabilities and should know how to seek help. GPs should be able to refer patients with long term sequelae to a suitable healthcare professional for specialist advice.

ERNIE database

The Evaluation and Review of NICE Implementation Evidence (ERNIE) database summarises the literature concerning the uptake of NICE guidance. References to external literature and a simple classification system are provided. ERNIE identifies 11 references that have assessed the implementation of the head injury guidelines [3]. Although this information is far from complete, it provides a sound introduction to further investigation and dissemination of knowledge about the impact of the guidelines. Initially an increased use in resources was considered likely [4,5]. However, this prediction has not been evident in studies published to date. The 2 to 5 times increased use of CT scans has been associated with a large decrease in admission rate. This has therefore led to a redistribution of patient management from the observation ward to the radiology department with no net increase in cost of care [6,7].

Areas for future research

The Guideline Development Group made several recommendations for further research to improve the evidence in specific areas of care. These are summarised below.

1. Should patients be transferred directly to a specialist neuroscience centre or to the nearest district general hospital?

2. The new guidelines regarding the use of CT head scans in children need validation in clinical practice.

3. The role of surgery vs. ICP and intensive care monitoring in patients with ‘non-surgical’ mass lesions requires further elucidation. Is there a role for ‘pre-emptive’ surgery?

4. Some evidence supports the transfer of patients with ‘non-surgical’ traumatic brain injury to a specialist neurosciences unit. This practice is not universal and further work is required to evaluate whether the reported improvements in outcome can be achieved across the board.

5. Robust clinical decision tools need to be developed to help predict those patients with mild injury who are likely to develop long term sequelae.

Conclusion

In summary, the NICE Head Injury Guidelines provide the many clinicians involved in the care of brain-injured patients with a sound foundation upon which to build patient care. The challenge for neurosurgeons is to improve the efficacy of management for patients with intracranial mass lesions and to conduct further work to establish the best pathway of care for patients with diffuse brain injury. Neurosurgeons are well placed to aid national guideline implementation.

References

- CG4. Head injury: triage, assessment, investigation and early management of head injury in infants, children and adults. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/headinjury_full_version_completed.pdf

- CG56. Head injury: triage, assessment, investigation and early management of head injury in infants, children and adults. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG56NICEGuideline.pdf

- ERNIE Head injury. http://www.nice.org.uk/usingguidance/evaluationandreviewofniceimplementationevidenceernie/searchernie/resultsummary.jsp?o=10918

- Sultan HY, Boyle A, Pereira M, Antoun N, Maimaris C. Application of the Canadian CT head rules in managing

minor head injuries in a UK emergency department: implications for the implementation of the NICE guidelines. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:420-5. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2003.011353 - Macgregor DM. McKie L. CT or not CT: that is the question. Whether ‘tis better to evaluate clinically and x-ray than to undertake a CT head scan! Emerg Med J. 2005;22:541-3.

- Hassan Z, Smith M, Littlewood S et al. Head injuries: a study evaluation the impact of NICE head injury guidelines. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:845-9. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2004.021717

- Dunning J, Daly JP, Malhotra R et al. The implications of NICE guidelines on the management of children presenting with head injury. Arch Dis Childhood. 2004;89:763-7.