Key take home messages

- Facial rehabilitation is a clinical specialism that aims to improve outcomes for people with facial weakness.

- Optimal treatment requires an individualised package of care from a multidisciplinary team.

- Clinically meaningful improvements are possible in persons with acute and chronic facial weakness.

- Clinicians develop skills and knowledge of facial movement dysfunction after insult to the facial neuromotor system resulting in advanced competencies and skill sets.

Facial weakness resulting from damage to the corticobulbar tract, the facial nucleus or the facial nerve and its branches, causes resting and dynamic facial asymmetry. This can impact on eating, drinking, speech sound production and eye health, as well as psychosocial well-being and participation. Facial weakness is commonly associated with conditions such as Bell’s palsy, Ramsay-Hunt Syndrome, Guillain-Barré Syndrome and its variant, Miller-Fisher Syndrome. Other causes include traumatic brain injury, skull base trauma, and cortical and subcortical strokes. Damage to the facial nerve may also result from direct injury or tumour resection. The resulting facial weakness can be unilateral or bilateral and can vary from a transient presentation to a more persistent and devastating weakness. There is emerging evidence for the effectiveness of facial rehabilitation; a process that involves facilitating intended facial movement patterns as well as eliminating unwanted movements to advance recovery of the facial nerve [1-6] and the facial motor system.

A number of studies have shown statistically significant and long lasting improvements after facial rehabilitation in persons with Bell’s palsy [2,3,6]. A Cochrane review [5] also reported evidence for tailored facial exercises to improve facial function for people with chronic and moderate facial weakness. The reviewers suggested that facial exercise could also reduce secondary sequelae in acute cases.

Facial rehabilitation aims to provide education on the cause of facial weakness, enhance the recovery of facial expression and function and improve social participation and well-being [1]. This is done through optimisation of facial symmetry and alignment as well as increased movement in facial expressions and function.

Frequent individualised goals include:

- Improved eye closure;

- Increased ability to smile/produce a more symmetrical smile;

- Increased self-confidence;

- Improved eating and drinking competence;

- Improved ease and clarity of speech sounds;

- Improved size of eye aperture;

- Ease of applying makeup;

- Return to playing wind instruments;

- Jaw/mouth opening.

In published studies, improvements in facial function are demonstrated using the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System (SFGS). The SFGS is a clinician-graded performance based measure of facial impairment which reflects improvement in both resting and dynamic symmetry and a reduction of mass movements. The SFGS assesses resting posture of the eye, nasolabial fold and corner of mouth; voluntary movement for five standard facial expressions in five regions of the face (forehead wrinkle, eye closure, open mouth smile, snarl and pucker) and synkinesis, associated with voluntary movement. Its psychometric properties have been defined including construct validity and responsiveness for clinically meaningful change and inter-rater and intra-rater reliability [7]. Measurement of synkinesis however has been found to be less reliable [8].

Therapeutic management for people with facial weakness includes detailed assessment, incorporating observational analysis of both sides of the face, backed up by reliable, valid and sensitive evaluation measures, including patient-graded instruments such as the Facial Disability Index (FDI) which considers the impact of facial weakness on both physical and social/well-being function, the FaCE Scale which is a measure of facial impairment and disability and the EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L) which can identify low mood and/or pain associated with health conditions.

In addition to observational analysis, assessment employs palpation to identify specific areas of stiffness as well as significant areas of weakness. This allows for the generation of an individually tailored neuromuscular facial programme, as indicated by the individual’s clinical presentation. This is an important shift away from historically prescribing non-specific exercises, which often promote exaggerated facial movements and secondary complications. Treatment intervention focuses on centring the face by using specific self-stretches to improve muscle length and three to five facial exercises, with emphasis on the muscles being in appropriate alignment, with inhibition of contralateral over-activity and/or synkinesis.

Mirror feedback, due to a lack of facial muscle proprioceptors [9] and perfect practice are key elements in neuromuscular rehabilitation. Taping, either facilitatory or inhibitory, may also be used as an adjunct to an individual’s facial programme. Additionally therapeutic mobilisation of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) may facilitate improved mouth opening in both acute and chronic cases [10].

When there has been damage to the facial nerve and/or its branches, recovery may be complicated by synkinesis. Synkinesis describes abnormal involuntary movement of one set of facial muscles that accompanies purposeful movement of a different muscle group [11] and may be part of the natural recovery. Common presentations include oculo-oral, involuntary mouth movement on eye closure and oral-oculo, involuntary eye closure on mouth movement, as well as synkinetic activation of the platysma muscle. Clinically, synkinesis is presumed to be due to aberrant axonal regeneration [12] but it has also been hypothesised to result from ineffective myelination leading to cross-talk between terminal facial nerve branches, or a centralised, post injury hypersensitisation of the facial nucleus [13]. The adjunctive use of low dose botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) injections in an individual’s facial programme can selectively weaken synkinetic muscles and improve resting and dynamic symmetry [6,11,14,15], especially when over-activity of the contralateral side of the face is also taken into account. BoNT-A is a potent neurotoxin produced by clostridium botulinum which inhibits the release of presynaptic acetylcholine from the neuromuscular junction when injected locally, causing temporary muscle weakness. The BoNT-A molecule is synthesised as a single inactive chain (150 kDa) and then cleaved to form the active di-chain molecule, made up of a heavy chain of ~100 kDa and a light chain of ~50 kDa, held together by a disulphide bridge. The light chain acts as a (zinc-dependent) metalloprotease with proteolytic activity located at the N-terminal end. After the heavy chain is injected, toxin binds to presynaptic receptors on the terminal ends of neurones, and the peptide enters the cytoplasm through endocytosis. Once in the cytoplasm, the light chain cleaves components of the SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimidesensitive factor attachment protein receptor), a complex of proteins necessary for the exocytosis of acetylcholine. In the case of BoNT-A, this specific site is known as SNAP-25 (synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kD). As a result of this cleavage, acetylcholine remains in the neurone, and is unable to bind to receptors on muscle fibres and stimulate muscle contraction (chemodenervation). The effect is short-lasting (three to four months) and weakened muscle recovers over time. The duration of action and turnover of the metalloprotease within the nerve terminal cytoplasm appears to be the predominant, but not the only factor that contributes to the duration of paralysis. Other factors may include transient neural sprouting and re-innervation, although the role of this phenomenon is unclear in humans [16-21.

The use of BoNT-A is well established for the treatment of hemifacial spasm and blepharospasm. There is accumulating evidence from prospective clinical studies for the use of low dose BoNT-A injections in conjunction with facial rehabilitation [6,11,14]. Lower doses of BoNT-A injections are used to treat synkinesis, compared to other facial dyskinesias, to avoid adverse reactions such as excessive weakness, ptosis and diplopia. Lower doses have been reported to be as effective as higher doses [22].

Contralateral lower quadrant facial sensorimotor impairment is common after a stroke and there is an abundance of evidence for neuromuscular plasticity [23]. Facial rehabilitation in the stroke population aims to exploit this phenomenon to enhance recovery of the facial neuromotor system. Intervention frequently incorporates the emotional motor system to produce spontaneous facial expressions [9] with the face centred (reducing contralateral over-activity) as well selective strengthening in function (talking, eating and drinking). Low dose BoNT-A injections may also have a role in managing contralateral over-activity in conjunction with facial rehabilitation.

The adjunctive use of electrical stimulation (ES) remains controversial following damage to the facial nerve and its branches. It has been suggested that ES may disrupt re-innervation and is thus contraindicated for individuals with facial nerve disorders [24]. However, some authors advocate that although ES used during the acute phase of Bell’s palsy is safe, it may not have added value over spontaneous recovery and multimodal physiotherapy [25]. An RCT involving 60 patients with acute Bell’s Palsy showed that an additional three weeks of daily ES sessions improved functional facial movements and electrophysiological outcome measures at three-month follow-up. The authors recommend further research on dosage and length of intervention [26].

With respect to ES and post stroke facial weakness, there is limited evidence for its use. However, two small studies found ES improved facial muscle strength and oral competence in people with dysphagia [27,28].

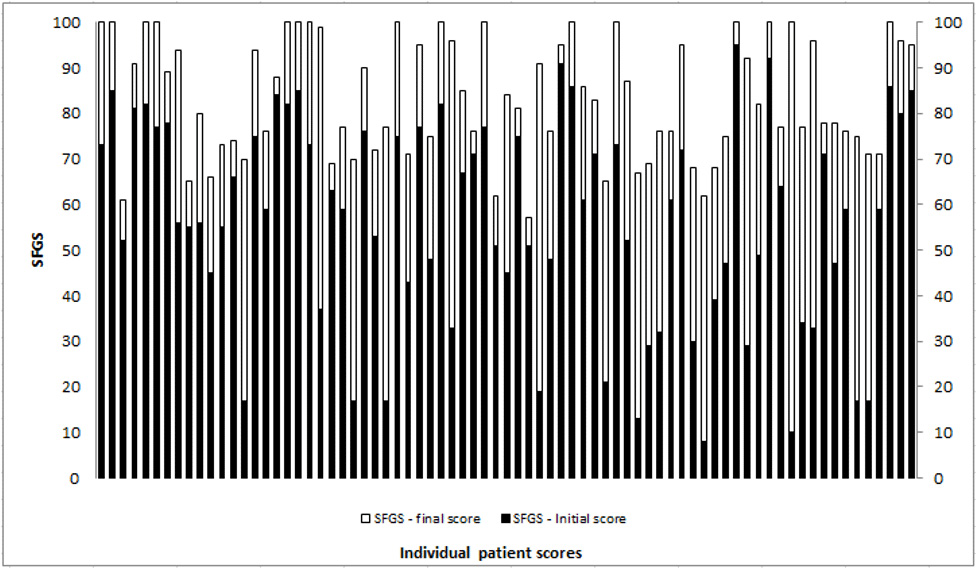

The Complex Facial Clinic at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, a clinical service that provides facial rehabilitation, was set up in 2011. The clinic is run jointly by a Clinical Specialist Physiotherapist and Highly Specialist Speech and Language Therapist and provides assessment and neuromuscular rehabilitation as well as offering the adjunctive use of low dose BoNT-A injections. The injection arm of the service is overseen by a Consultant Neurologist. Data collected using the SFGS shows the effectiveness of individualised facial rehabilitation with positive impact on resting and dynamic facial symmetry (Figure 1).

(worst) to 100 (best). The light grey/white demonstrates amount of change with facial rehabilitation intervention.

Table 1 illustrates examples of therapeutic interventions in relation to an individualised goal as part of the facial programme.

Table 1. | |||

Goal(s) | Target Muscle(s) | Examples of Therapeutic Input | Rationale |

Improved eye closure | Orbicularis oculi [orbital, pre-septal, and pre-tarsal muscle sections] | Selective stretch to the lower pre-septal fibres of orbicularis oculi and levator palpebrae; practice of gentle eye closure with the levator labi superioris muscle stabilised | Stiffness will impact on movement; need to isolate and selectively strengthen orbicularis oculi |

Increased ability to smile/improve smile symmetry | Zygomaticus major and minor; levator anguli oris | Selective stretches [contralateral external and internal cheek muscles; ipsilateral platysma]; practice of small range smile activity [with mental imagery] with slowing down of contralateral smile activity | To centre face and reduce any stiffness that will impact on excursion of movement prior to re-education of smile activity |

In summary, facial rehabilitation is a clinical specialism that can improve the quality of care and outcomes for people with facial weakness. Successful outcomes can be achieved using individually tailored programmes with clearly identified goals. Adjunctive treatment in selected individuals with BoNT-A injection can help optimise management. Clinicians need to develop in depth knowledge of the facial motor system and advanced competencies and skill sets in order to manage facial movement dysfunction. There is also a need for a description of optimal facial rehabilitation interventions using a format such as the template for intervention description and replication (TIDIER) guidelines.29 This could inform future clinical trials and help gain consensus amongst facial rehabilitation therapists across this specialism.

References

- VanSwearingen JM. Facial rehabilitation: a neuromuscular re-education, patient-centered approach. Facial Plastic Surgery 2008; 24(2): 250-59. 10.1055/s-2008-1075841

- Lindsay RW, Robinson M, Hadlock TA. Comprehensive facial rehabilitation improves function in people with facial paralysis: a 5-year experience at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. Physical Therapy 2010; 90: 391-97. 10.2522/ptj.20090176

- Pereira LM, Obara K, Dias JM, Menacho MO, Lavado EL, Cardoso JR. Facial exercise therapy for facial palsy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation 2011; 25(7): 649–58. 10.1177/0269215510395634

- Ferreira M, Santos PC, Duarte J. Idiopathic facial palsy and physical therapy: an intervention proposal following a review of practice. Physical Therapy Reviews 2011; 16(4): 237-43. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/maney/ptr/2011/00000016/00000004/art00002

- Teixeira LJ, Valbuza,JS, Prado GF. Physical therapy for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011; 7(12): CD006283. 10.1002/14651858.cd006283.pub3

- Watson GJ, Glover S, Allen S, Irving RM. Outcome of facial physiotherapy in patients with prolonged idiopathic facial palsy. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 2015; 129(4): 348-52. 10.1017/s0022215115000675

- Neely JG, Cherian NG, Dickerson CB, Nedzelski JM. Sunnybrook facial grading system: reliability and criteria for grading. Laryngoscope 2010; 120(5):1038-45. 10.1002/lary.20868

- Coulson SE, Croxson GR, Adams RD, O’Dwyer NJ. Reliability of the ‘Sydney’, ‘Sunnybrook’ and ‘House Brackmann’ facial grading systems to assess voluntary movement and synkinesis after facial nerve paralysis. Otolaryngeal Head Neck Surgery 2005; 132(4):543-49. 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.01.027

- Cattaneo L, Paves G. The facial motor system. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2014; 38:135–59. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.11.002

- Shaffer SM, Brismee JM, Sizer PS, Courtney CA. Temporomandibular disorders. Part 1: anatomy and examination/diagnosis. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy 2014; 22(1):2-12. 10.1179/2042618613y.0000000060

- Toffola ED, Furini F, Redaelli C, Prestifilippo E, Bejor M. Evaluation and treatment of synkinesis with botulinum toxin following facial nerve palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation 2010; 32(17):1414-18. 10.3109/09638280903514697

- Husseman J, Mehta RP. Management of synkinesis. Facial Plastic Surgery 2008; 24(2): 242-49. 10.1055/s-2008-1075840

- Cabin JA, Massry GG, Azizzadeh B. Botulinum toxin in the management of facial paralysis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery 2015; 23(4):272-80. 10.1097/moo.0000000000000176

- Lee JM, Choi KH, Lim BW, Kim MW, Kim J. Half-mirror biofeedback exercise in combination with three botulinum toxin A injections for long-lasting treatment of facial sequelae after facial paralysis. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 2015; 68:71-78. 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.08.067

- Sadiq SA, Khwaja S, Saeed SR. Botulinum toxin to improve lower facial symmetry in facial nerve palsy. Eye 2012; 26:1431–36. 10.1038%2Feye.2012.189

- Punga AR, Eriksson,A, Alimohammadi M. Regional diffusion of botulinum toxin in facial muscles: A randomised doubleblind study and a consideration for clinical studies with splitface design. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 2015; 95:948–51. 10.2340/00015555-2093

- Shoemaker CB, Oyler GA. Persistence of botulinum neurotoxin inactivation of nerve function. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013; 364:179–196. 10.1007%2F978-3-642-33570-9_9

- Pantano S, Montecucco C. The blockade of the neurotransmitter release apparatus by botulinum neurotoxins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014; 71, 793–811. 10.1007/s00018-013-1380-7

- Whitemarsh RC, Tepp WH, Johnson EA & Pellett S. Persistence of botulinum neurotoxin A subtypes 1–5 in primary rat spinal cord cells. PLoS ONE. 2014; 9, e90252. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090252

- Rossetto O, Pirazzini M, Montecucco C. Botulinum neurotoxins: genetic, structural and mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014; 12, 535–549. doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3295

- Eleopra R, Rinaldo S, Montecucco C, Rossetto O, Devigili, G. Toxicon 179. 2020; 84–91. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2020.02.020

- Laskawi R. The use of botulinum toxin in head and face medicine: an interdisciplinary field. Head & Face Medicine 2008; 4(1):5. https://head-face-med.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1746-160X-4-5

- Nudo RJ. Neural bases of recovery after brain injury. Journal of Communication Disorders 2011; 44:515–20. 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.04.004

- Manikandan N. Effect of facial neuromuscular re-education on facial symmetry in patients with Bell’s palsy: A randomized control trial. Clinical Rehabilitation 2007;21:338-343. 10.1177%2F0269215507070790

- Alakram P, Puckree T. Effects of electrical stimulation on House-Brackmann scores in early Bell’s palsy. Physiotherapy Theory & Practice 2010;26(3):160-6. 10.3109/09593980902886339

- Tuncay F, Borman P, Taser B, Unlu I, Samim E. Role of electrical stimulation added to conventional therapy in patients with idiopathic facial (Bell) palsy. American Journal Physical Medical Rehabilitation 2015;94(3):222-228. 10.1097/phm.0000000000000171

- Choi JB. Effect of neuromuscular electrical stimulation on facial muscle strength and oral function in stroke patients with facial palsy. Journal Physical Therapy Science 2016;28(9):2541- 2543. 10.1589/jpts.28.2541

- Oh DH, Park JS, Kim WJ. Effect of neuromuscular electrical stimulation on lip strength and closure function in patients with dysphagia after stroke. Journal Physical Therapy Science 2017;29(11):1974-1975. 10.1589/jpts.29.1974

- Hoffman TC, Glasziou PP, Boultron I, Milne R and others. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014; 348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687