In the diagnosis of the almost ubiquitous low back pain, with or without sciatic nerve radiation, there are few reliable physical signs. Restricted straight leg raising (SLR) is one of the most useful signs that indicates a lesion of the sciatic nerve roots by stretching, irritation or entrapment in or adjacent to the intervertebral foramen. Though commonly labelled Lasègue’s sign, Lasègue did not describe it in his published papers.

In 1881 his student Jean Joseph Forst first published the SLR test in his doctoral thesis and indicated that it was founded on Lasègue’’s observation. Lasègue was an accomplished physician who advanced the understanding of syphilitic GPI (General Paralysis of the Insane), delusional states, and other psychological disorders.

Sciatica has been described since Greek and Roman times. Oppenheim and Krause, Goldthwait and Walter Dandy identified a ruptured disc, often previously labelled a chondroma, as a cause of sciatica [1]. Only after the paper of Mixter and Barr [2] in 1934 was a prolapsed lumbar disk generally accepted as its commonest cause [3].

In the diagnosis of the almost ubiquitous low back pain, with or without sciatic nerve radiation, there are few reliable physical signs. Restricted straight leg raising (SLR) is one of the most useful signs that indicates a lesion of the sciatic nerve roots by stretching, irritation or entrapment in or adjacent to the intervertebral foramen. Though commonly labelled Lasègue’s sign, Lasègue did not describe it in his published papers.

His idea of using straight leg raising began when he watched his son in law Cesbron, tuning his violin:

“Is not the string stretched over the bridge like the sciatic nerve which is made taut on the ischium when the lower extremity is elevated?”

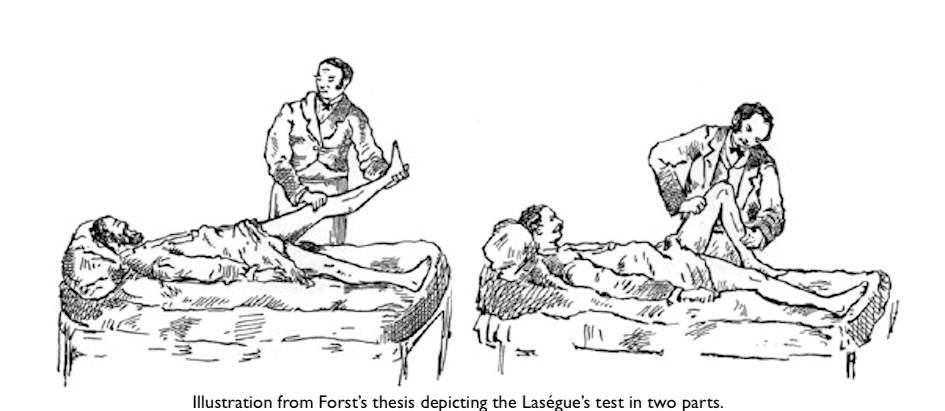

Lasègue’s paper Consideration sur la sciatique in 1864 contains no mention of the sign that bears his name [4]. But in 1881 his student Jean Joseph Forst first published the SLR test in his doctoral thesis [5]: “It was our teacher Professor Lasègue who pointed our attention to this sign.” Forst described his master’s test in two stages:

The patient is placed on the bed in the supine position, and we take the foot of the affected limb in one hand…holding the leg in extension, we flex the thigh on the pelvis. Raising the limb only a few centimetres produces a sharp pain at the level of the sciatic notch…We replace the limb and proceed to another manoeuvre which is only a confirmatory test. If we now flex the leg on the thigh, we can flex the thigh on the pelvis without producing any painful sensation.

Figure 1: Illustration from Forst’s thesis depicting the Laségue’s test in two parts. From: Kshitij Chaudhary.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8046483/

It seems likely that having demonstrated it to Forst and thought about its mechanism Lasègue did use the sign in his clinical work, but probably after his paper in 1864 [4]. It was wrongly attributed to stretching the hamstring muscles until De Beurmann in 1884 showed the stretching was of the sciatic nerve itself [1]. However, shortly before Forst’s paper, Lazar K. Lazarevic, a Yugoslavian physician in 1880 had described the sign in six patients, in the Serbian Archives of Medicine (later reprinted [6]).

Ernest Charles Lasègue (1816-83) as an impecunious student was a friend of Claude Bernard and a favourite pupil of Trousseau in Paris, where he studied medicine (1839-47). In 1848, he was sent by the French government, to Southern Russia to investigate a cholera epidemic. In 1853 he won his agrégation with a thesis on general paralysis. The same year he became co-editor of the Archives générales de médecine. Trousseau appointed him Chef de Clinique in 1852. He was appointed Professor of Clinical Medicine at the Salpêtrière Hospital, and was by repute: “forever after malingerers.”

Lasègue was an accomplished physician who advanced the understanding of syphilitic GPI (General Paralysis of the Insane), and several other psychological disorders. They included delusional states, persecution mania, and hysterical anaesthesia with ataxia. He related the histories of eight patients suffering from anorexia nervosa, De l’Anorexie Hystérique in 1873, a condition not commonly recognised despite Richard Morton’s description in 1689. With Fairet he described folie a deux, a psychological disorder in which they believed delusional symptoms were transferred from one psychotic individual to a closely associated healthy person [7]. He was also an authority on alcoholism, based on patients whom he had examined in police hospitals. In an account of rheumatic fever he shrewdly observed: “Rheumatic fever licks the joints but bites the heart.” He laboriously reviewed “the Pathological Anatomy of Cretinism,” but failed to implicate the thyroid gland.

A diabetic himself, at a clinical lecture at the Hôpital de la Pitié, in 1882 he divided diabetic patients into two classes: fat and lean; and also into small-patients that excrete 20 gm. of sugar a day and great—more than 30 or 40 gm./day in their urine. The glycosuria could be intermittent though he thought this had little consistent effect on prognosis.

He had a famous dispute with Virchow about his cell theory, which stated: Omnis cellula-e-cellula. Lasègue argued that disease of the cells was only a fragment of pathology. Virchow replied that he was incompetent, to which Lasègue scathingly responded that the laboratory could not contribute anything to medicine.

He was a witty, unpretentious man, who was both attentive and assiduous in understanding his patients. He supported the arts, and education based on the humanities. He died from complications of diabetes in 1883 aged sixty-six.

References

- Chaudhary K. The History behind the Discovery of Root Tension Signs and the Invention of the Lumbar Discectomy Surgery. J Orthop Case Rep. 2021;11(1):121-126. https://doi.org/10.13107/jocr.2021.v11.i01.1992

- Mixter WJ, Barr JS. Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. New Engl J Med 1934;211: 210 – 14. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM193408022110506

- Pearce JMS. The lumbar disc syndrome. Postgrad Med J 1969; 45(522): 278-284. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.45.522.278

- Lasègue C. Considérations sur la sciatique. Arch Gen Med 1864;6(4):558-8.

- Forst JJ. Contributions a l’Etude Clinique de la sciatique. Thèse pour le Doctorat en Médecine, Paris : Faculté de Médecine de Paris, 1881. Translated In: Lasègue’s Sign. Wilkins RH, Brody IA. Arch Neurol 1969;21:219-21.

- Lazarevic LK. Ischias postica Contunnii : Ein Beitrag zu deren Differential-Diagnose. Allg Wien Med Ztg 1884;29:425 – 26 et seq

- Arnone D, Patel A, Tan GM. The nosological significance of Folie à Deux: a review of the literature. Annals of General Psychiatry 2006;5:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-5-11