Despite a considerable number of reviews, from high level political statements to local initiatives, the pace of service development for people with neurologic conditions remains slow. The Neurological Alliance recent 2017 review1 of patient experience makes a disheartening read, showing a worsening of many metrics, including an increased proportion of patients needing to see their GP five times or more before a specialised referral was made and a decreasing number who feel involved in making choices, or that their health care professionals work together well “at least some of the time”. Unfortunately, the system does not seem to learn from its mistakes. In 2012, The House of Commons Public Accounts Committee2 released an important report on services for patients with neurological conditions. It concluded that the implementation of the National Service Framework3 for Long Term Conditions had failed, causation including a lack of leadership at a national and local level, poor data, huge postcode variation in expertise, poor integration of health and care and a paucity of quality standards.

Part of the NHS response to this was to appoint a National Clinical Director (NCD) for neurological conditions and establish Strategic Clinical Networks (SCNs) in 2013 to drive local developments. The NCD catalysed many important developments, including the development of the much-needed Neurology Intelligence Network whose “fingertips” publications have been considerably illuminating. However, was it all just a sop to the politicians? In a further 2016 review NHS England reported to the same committee that the NCD would not be reap- pointed, but instead neurology would be led in a collaborative way “based around strategic clinical networks”. So, it’s noteworthy that the strategic clinical networks were dissolved shortly after this statement.

However, were the SCNs cutting the mustard? In some areas yes, but unlike all the other priority area SCNs such as mental health, cancer, dementia*, stroke* (neurological conditions largely managed by other specialists*), there has been no alignment with clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) operational frameworks. Hence it is not incumbent on CCGs to improve services for patients with neurological conditions, whereas they have to report on specific actions, for example in patients with dementia. It is important to realise that the rate limiting step is usually business capacity rather than financial restriction. So, running a programme of change in a sustainable way is incredibly hard when the only driver is local enthusiasm.

So, what is the problem? After all there are 2 million people in the UK with a neurological condition (excluding migraine) and we are spending over £2 billion in un-coordinated health services and the same amount again in care. Neurological conditions account for 10% of all hospital admissions, 17% of all emergency admissions and 10% of consultations in primary care. A snapshot of information from four local authorities suggests that 50% of people aged 18–65 receiving social services support have a neurological condition. If this were extrapolated for England, it would equate to about 63,000 people aged 18–65 with a neurological condition needing such help.4

Why neurology has not been able to articulate a national message and remained invisible is only speculative. If I was a cynic I would suggest it’s rooted in a cultural indifference to people with neurologic disabilities. One of my patients recently asked me why if you have cancer and are trying to get back to work everyone is bending over backwards to help, but his experience (following a stroke leaving him only with mild dysarthria) was to be shown the way to the car park.

Credible proposals to modernise the way neurology is delivered are simple including that:

- The management of common neurologic conditions in primary care could be stronger (in many areas).

- Systematic ownership could be taken at a secondary care level by Neurologists for emergency and urgent care.

- Variation in access and services offered by neuroscience centres and local hospitals could be reduced.

- Outpatient neurological services models need rethinking as they are often unresponsive to need, clogged with unnecessary referrals, and operate on a top heavy one in one out model.

- Management of neurological crises in the community could be strengthened – lack of knowledge/confidence, unresponsiveness all result in waiting for an outpatient appointment or reliance on A&E with subsequent unplanned admission.

This involves people working in a different way, such that more of the precious resource is shifted from outpatients to acute and community settings, interfacing with integrated care systems in the community and building important relationships.

Acute neurology

In London, we undertook an audit examining the delivery of neurology at a secondary care level,5 finding no hospital offering first line assessment and admission of patients with neurologic conditions by Neurologists. Considering the mass of Neurologists at some regional centres this is notable. UCL Partners undertook an evaluation for us of “hyperacute neurology services” based on the concept of hyperacute stroke units but evaluating different models whose commonality was a reorganised front end with earlier senior input. This was trialled in four teaching hospitals, though DGH models exist.

We found that:

- A&E admissions of patients managed by the service were reduced.

- Early diagnosis improved with more appropriate use of diagnostics.

- Readmissions of patients managed by the service was reduced, partly through appropriate signposting. (e.g. patients with epilepsy were organised to attend seizure clinics)

- Inpatient transfers to tertiary neuroscience centres were reduced.

The increase in breadth of diagnosis was considerable (30 fold), but perhaps not surprising if the generalists’ differential diagnosis for severe headache is subarachnoid haemorrhage or subarachnoid haemorrhage. It turned out there was no need for a hyper-acute neurology unit as the actual numbers requiring admission were very small, and the concept of the next day acute medical unit round became redundant (there were few neurology patients on it).

Integrating care

Outpatient referral rates for adult neurology published by Public Health England reveal staggering variation. In Camden CCG, the rate is 2470 per 100 000 per annum and in Doncaster CCG its 147.6 Despite this 17-fold variation the rates for unplanned admission are much the same, so you could argue that having considerable outpatient access does not prevent unplanned admission.

This is a key issue for patients with long term conditions where services have traditionally been organised around the secondary and tertiary sector. Other services e.g. therapists, social services often require a separate referral and delayed access to expert advice, particularly at times of crisis.

Explicit coordination and integration improves movement through care pathways by reducing duplication, avoiding suboptimal pathways, and minimising risk. It can also enhance prevention activity and rehabilitation. Better co-ordination reduces emergency admissions to hospital or unsafe discharge, and improves the provision of information for self-management.

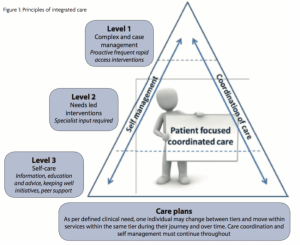

The principles of integration are simple and include:

- Case ascertainment

- Care planning

- Promotion of self-management

- Risk stratification for crisis avoidance

- Community MDT working (Figure 1).

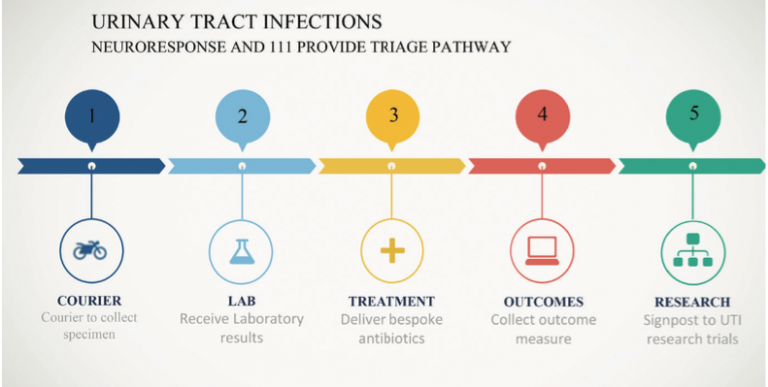

Most of this is generic and more than deliverable for patients with neurological conditions, requiring minimal, highly specialised support. Usually the most important person in the MDT is the psychologist. An exemplar has been developed by the Thames Valley SCN who have launched a new commissioning brief7 to support local commissioners to improve the services provided in community settings to people diagnosed with a long-term neurological condition. Ground breaking work has also come from Bernadette Porter, a Nurse Consultant who has developed a unique telephone based system “Neuroresponse” to guide patients in crisis into appropriate care settings from the outset and avoid the pinball effect where no one in multiple agencies can / will take responsibility. She has also identified urinary tract infection as a major cause of unplanned admission for patients with LTCs and is trialling community intervention (man on a bike) for early diagnosis and prevention of systemic complications (Figure 2).

Common conditions

It’s easy to say that more common conditions could be managed in primary care but being a GP at present must be a great challenge with a huge raft of conditions being pushed out of the secondary care sector. Education is laudable and we and others have produced a series of video casts to guide management of common conditions. These have had thousands of views but I doubt they impact on referral rates in isolation. Referral management alone certainly delivers restriction but is a blunt tool compared to improving communication between primary and secondary care. Talking to GPs never imbues me with confidence that we (Neurologists) as a generalisation are great at this. London has a high rate of neurology referrals to hospital outpatient departments (OPD) compared to England; 30 of 32 London CCGs have referral rates greater than the England average. We estimated that 50 to 60 percent of referrals are for common conditions, and 30 percent of these could have been managed in the community. However more appropriate models could be within the multispecialty community provider model which could:

- Improve response time and diagnosis averting the development of chronic problems.

- Reduce outpatient appointments for common conditions by 17 percent.

- Encourage rational prescribing, as specialist reviews are likely to standardise drug usage, cost effective use of available drugs (generics over branded), counsel on lifestyle impacts on the condition (e.g. migraine, manage medication overuse headache).

- Reduce ambulance callouts.

- Provide active referral management both into the integrated system and onward to secondary care.

- Allow dissemination of skills across the primary/secondary care interface.

- Co-ordinated care between primary and secondary care; improved collaboration and communication.

The near future

There remain several ongoing mechanisms for improvement. NHS England have established a National Advisory Group on Neurologic Conditions. With its leadership aligned with the neuroscience CRG this looks exciting. The “Right Care” concept is providing a significant window into local conversations with commissioners, though its output poses another round of questions. As its core principle is variability it will not produce a sting where provision is universally poor. The “Getting it Right First Time” concept also is seeking to establish a neurological conditions programme, principally working at a secondary care level. However, the key requirements for commissioners at a local level to deliver for neuroscience remain absent. We previously lobbied NHS England to get some development of this but it wasn’t going to happen. The issue was prioritisation, which is a fair enough principle though still makes little sense to me on a public health basis.

References

- “Falling Short – How has neurology patient experience changed since 2014?”, Neurological Alliance, 2017: http://neural.org.uk/updates/278-New-Neurological-Alliance-patient-experience-report-2017

- House of Commons. Committee of Public Accounts. Services for people with neurological conditions. Seventy-second Report of Session. 2010–12. https://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/ cmpubacc/…/1759.pdf

- National service framework for long term conditions. 2005. Department of Health.

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/quality-standards-for-supporting- people-with-long-term-conditions

- Neuro numbers. 2014. Neurological Alliance and MHP Health Mandate http://www.neural.org.uk/store/assets/ les/…/Final_-_Neuro_Numbers_30_ April_2014_.pdf

- London organisational audit of secondary and tertiary neurological care provider.s

- http://www.londonscn.nhs.uk/networks/mental-health-dementia neuroscience/ neuroscience/quality-and-safety/

- https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile-group/mental-health/profile/neurology

- http://www.londonscn.nhs.uk/networks/mental-health-dementia-neuroscience/ neuroscience/integration-and-coordination/