Abstract

People with aphasia are often unable to access healthcare due to difficulties understanding and using spoken and written language, which impacts every step of their healthcare journey and outcomes. This article argues that it is important to apply the principles of the NHS England Accessible Information Standards (2017) to people with aphasia so they can meet their health information needs and rights. The processes to enable people with aphasia to access and participate in spoken and written communication in healthcare and the methods for training and supporting healthcare staff need to be considered at an individual, service, and organisational level.

The accessible information standards (2017) state the need for organisations to ensure that individuals receive information in an accessible format and any communication support they need [1]. Whilst the accessible information standards relate primarily to people with sensory impairments and learning disabilities, this paper will outline the rationale, methods, and strategies for applying similar principles for people with aphasia.

Successful communication between healthcare professionals and patients is essential for engaging patients in their healthcare and improving outcomes [2]. Spoken communication is the medium through which information is exchanged and decisions made between healthcare professionals and their patients [2]. Written information is used to supplement education and support informed decision making [3]. People with aphasia have the same health information needs and rights as everyone else, however due to their language impairments, they are likely to struggle to understand spoken and written information [2,3]. Ineffective communication with people with aphasia can lead to frustration, exclusion from healthcare services and decision making, higher rates of medical errors and patient dissatisfaction [2,3,4]. This is further impacted by the limited knowledge, skills, and attitude of the healthcare professional [2,5].

Healthcare professionals acknowledge the challenges in communicating with people with aphasia. Communication impairments impede all healthcare activities including assessment, diagnosis, care, education, and therapy [6]. However, healthcare professionals often do not receive formal training in how to communicate with people with aphasia [2].

Consequently, written information needs to be adapted to enable people with aphasia to read with understanding [7]. Healthcare professionals should receive communication partner training interventions to enable participation of people with aphasia in their healthcare [2,8].

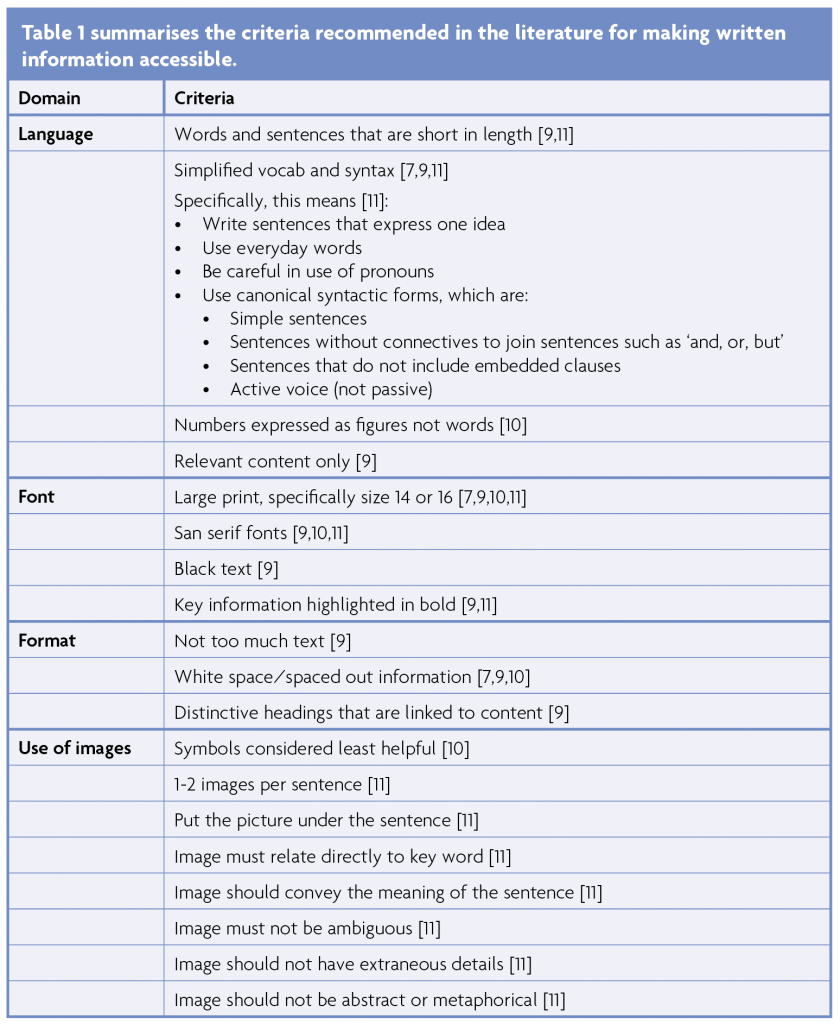

Making written information accessible

The aphasia literature highlights the benefits of making written information ‘aphasia friendly’. It improves the ability to read and understand written information [3,7]. It increases knowledge and improves confidence [3]. Perhaps most importantly, it is preferred by people with aphasia [9]. However, it is acknowledged that there is no definition of ‘aphasia friendly’.

A number of studies have set out to determine the criteria for aphasia friendly written material. There appears to be good consensus on the most beneficial adaptations of language, font, and formatting. Most studies agree on the need for ‘simple language’, large and sans serif fonts, highlighting key words in bold, minimising volume of text, and spacing out information [7,9,10,11]. However, the use of images and the length of adapted written material have proved more controversial. Some studies report no significant benefit of supporting written information with pictures [7]. The preference of people with aphasia varies. [3] However, the potential advantages of images are multiple and include: helping reading comprehension, adding interest, adding enjoyment, and aiding memory [9]. Consequently, most studies recommend the use of pictures unless considered unhelpful by the person with aphasia [9,10]. Length is similarly contentious. Making written information aphasia friendly tends to increase the length of the material. This is a source of complaint for some people with aphasia [3] and is considered by some to place increased demand on working memory [7]. However, it is preferred by others provided the information is formatted appropriately [10].

Communication partner training

Communication partner training is an environmental intervention that trains individuals to use strategies and communication resources in their interactions with people with aphasia [12,13,14], and possibly the person with aphasia themselves [13]. The main aim is to increase the knowledge and communication skills of those trained and to improve the participation of people with aphasia in social or healthcare conversations [13]. It has been shown to yield positive outcomes for a range of aphasia severity levels and a range of communication partners, including healthcare staff [12,13].

Communication partner training can be person-specific or generic [12]. Generic communication partner training can be used to teach healthcare staff to use supportive techniques and materials that are applicable across people with aphasia in healthcare contexts [12]. Clinicians who receive communication partner training report increased knowledge, confidence, and skills in communicating with people with aphasia [2,5,13]. Furthermore, training can lead to service-level change for the benefit of people with aphasia [5]. However, there is some suggestion that training alone is not sufficient [5,6]. Opportunity for follow-up support or coaching sessions, practice in clinically relevant situations, and making relevant resources accessible appear to drive greater implementation success in combination with favourable organisational conditions [5,14]. Organisational change and support are key given that lack of leadership, time, workplace culture, and workload pressures pose the greatest barriers to implementation of communication partner training [5,6,14].

Consequently, when healthcare professionals are asked to describe their needs for communicating with people with aphasia, they ask for [8]:

- Increased knowledge of aphasia

- Increased skills in engaging with people with aphasia and training to use communication techniques and tools

- Organisational change such as provision of more time and adapting resources so they are aphasia friendly

- Changing the role of Speech & Language Therapists to provide training, act as role models, provide in-situ coaching, and make communication tools that are accessible to all healthcare professionals.

The role of SLTs in providing training, advocating for people with aphasia, and providing ongoing support is highlighted elsewhere in the literature [2,15].

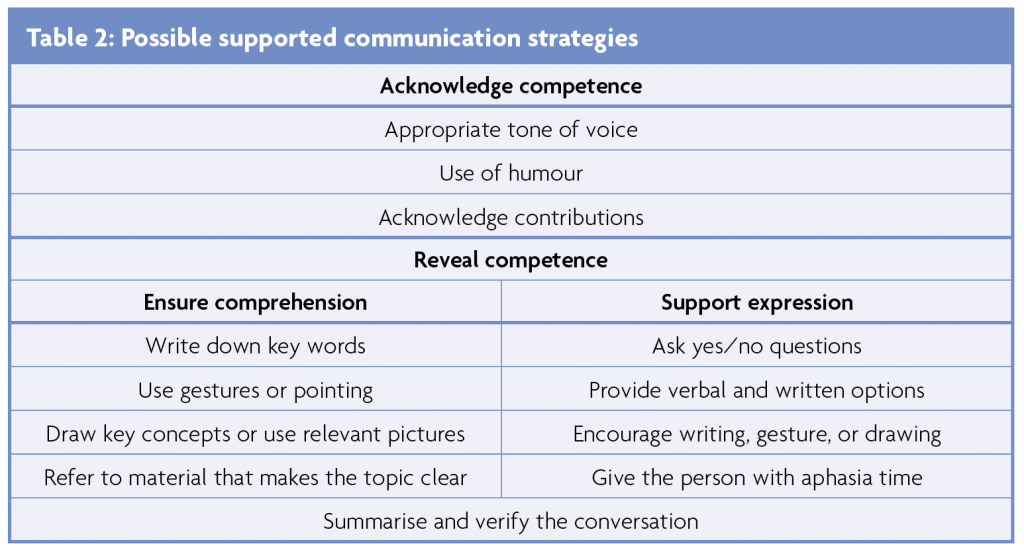

Many communication partner training programmes have their origin in ‘Supported Conversations for Adults with Aphasia’ (SCA), which provides the communication partners with the methods and materials needed to support conversations with people with aphasia [15]. SCA advocates for communication partners acting as a resource for people with aphasia and to actively share responsibility for communication success [15]. Table 2 outlines some possible supported communication strategies from SCA [15].

Conclusion

In conclusion, making information accessible for people with aphasia in healthcare needs to be a key priority at an organisational level. The above overview of the literature has identified that due to inaccessibility of information, people with aphasia are not having their healthcare needs and rights met; this is impacting all their healthcare activities and outcomes. The literature also acknowledges the challenges faced by healthcare workers when giving spoken and written information to people with aphasia. To address this, the role of Speech and Language Therapists should evolve to encompass provision of training and support to healthcare workers to meet these needs. This will ensure that people with aphasia are able to access healthcare information equitably alongside everyone else.

References

- NHS England. Accessible Information: Specification v.1.1. 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/accessible-information-standardspecification/

- Burns MI, Baylor CR, Morris MA, McNalley, Yorkston KM. Training healthcare providers in patient–provider communication: What speech-language pathology and medical education can learn from one another. Aphasiology. 2012:26(5);673-688. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2012.676864

- Rose T, Worrall, L, McKenna, K. The effectiveness of aphasia‐friendly principles for printed health education materials for people with aphasia following stroke. Aphasiology. 2003:17(10);947-963. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030344000319

- Bartlett G, Blais R, Tamblyn R, Clermont RJ, MacGibbon B. Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. CMAJ. 2008;178(12):1555-62. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.070690

- Simmons‐Mackie NN, Kagan A, O’Neill Christie C, Huijbregts M, McEwenm S, Willems, J. Communicative access and decision making for people with aphasia: Implementing sustainable healthcare systems change. Aphasiology 2007:21(1);39-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030600798287

- Van Rijssen MN, Veldkamp M, Bryon E, Remijn L, Visser-Meily JMA, Gerrits, E, van Ewijk L. How do healthcare professionals experience communication with people with aphasia and what content should communication partner training entail? Disability and Rehabilitation 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1878561

- Brennan A, Worrall L, McKenna. The relationship between specific features of aphasia-friendly written material and comprehension of written material for people with aphasia: An exploratory study. Aphasiology. 2005:19(8);693-711. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030444000958

- Van Rijssen M, Veldkamp M, Meilof L, van Ewijk L. Feasibility of a communication program: improving communication between nurses and persons with aphasia in a peripheral hospital. Aphasiology. 2019:33(11);1393-1409. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2018.1546823

- Rose TA, Worrall LE, Hickson LM, Hoffmann, TC. Aphasia friendly written health information: Content and design characteristics, International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2011:13(4);335-347. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.560396

- Rose TA, Worrall LE, Hickson LM, Hoffmann, TC. Guiding principles for printed education materials: Design preferences of people with aphasia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2012:14(1):11-23. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.631583

- Herbert R, Gregory E, Haw C. Collaborative design of accessible information with people with aphasia. Aphasiology. 2019:33(12);1504-1530. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2018.1546822

- Simmons-Mackie N, Raymer A, Cherney LR. Communication Partner Training in Aphasia: An Updated Systematic Review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2016;97:2202-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.03.023

- Cruice M, Blom Johansson M, Isaksen J, Horton S. Reporting interventions in communication partner training: a critical review and narrative synthesis of the literature. Aphasiology. 2018:32(10);1135-1166. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2018.1482406

- Shrubsole, K, Lin TJ, Burton C, Scott J, Finch E. Delivering an iterative Communication Partner Training programme to multidisciplinary healthcare professionals: A pilot implementation study and process evaluation. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2021:56;620-636. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12618

- Kagan A. Supported conversation for adults with aphasia: methods and resources for training conversation partners. Aphasiology. 1998:12(9);816-830. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687039808249575