Neurobehavioural disability (NBD) resulting from acquired brain injury (ABI) potentially has significant consequences, including challenging behaviour which is a greater long-term impediment to community reintegration than physical disability.1 Consequently, availability of reliable, valid means of assessing NBD is highly desirable. Standardised measures have known psychometric properties that inform validity and reliability. However, a review of well-known NBD measures revealed that many were lacking these properties, rendering measurement problematic.2

The ‘St Andrews – Swansea Neurobehavioural Outcome Scale’ (SASNOS) was developed to fill this gap.3 Forty nine items capture five major domains of NBD, each of which has 2-3 subdomains. Items comprise a statement regarding a symptom of NBD, rated using a seven-point scale. Assessment follows observation of a person over a two week period.

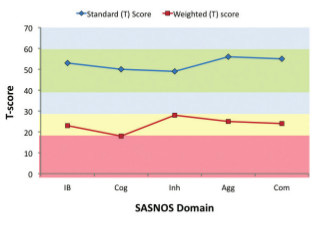

A major strength of SASNOS is availability of data from neurologically healthy people, facilitating identification of NBD symptoms in individuals with ABI more prevalent than amongst the general population. Ratings are transformed to standard scores with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10; higher scores reflect less NBD symptoms. SASNOS has robust psychometric properties, meaning single assessments of NBD produce dependable results.

Since 2011 SASNOS has seen international use, including Australia, Canada, Demark, Spain, The Netherlands, Ireland and New Zealand. Within the UK, it has been endorsed by organisations providing neurorehabilitation and it is routinely used to monitor clinical and cost-effectiveness of services.

Developing the instrument has forged strong partnerships between Swansea University and health providers, most significantly Partnerships in Care, which has a growing network of neurobehavioural rehabilitation services, the most recent of which is Manor Hall near Stirling. Currently, there is little specialist provision of this type in Scotland so the imminent launch of this new service is welcome news.

An early account of SASNOS was described previously in ACNR.4 Collaboration between Swansea University and Partnerships in Care continues to foster research to improve the instrument for the benefit of patients. Three innovative developments will be briefly described.

First, context is critical to the meaningful interpretation and application of SASNOS scores. Ratings made concerning patients in residential rehabilitation programmes will reflect prevalence of behaviours and functional abilities in the context of rehabilitation; it cannot be assumed that results obtained will have universal validity and be generalisable to other settings (e.g., home, community). Sometimes ratings are comparable with neurologically healthy people and can provoke discharge to a less restrictive placement. However, whilst rehabilitation ideally results in long-lasting change, some improvements require ongoing support which standardised assessment scores in the ‘normal’ range do not indicate by themselves. This increases the risk of some people being discharged without the support needed to maintain autonomy.

In response to this, we propose that supplementary dependency ratings are completed for each SASNOS item in preparation a.5 Dependency ratings calibrate standard scores to estimate the effect on ratings without support. If the person is truly autonomous, standard and weighted SASNOS scores are identical. However, where provision of support underpins absence of NBD symptoms, there is clear dissociation between scores (see figure 1). In their paper, the authors articulate reasons for making supplementary dependency ratings, describe profile types emerging from these, present an illustrative case example, and report the results of a user survey testifying to the validity and clinical usefulness of the new development.

The second innovation concerns responsiveness, the ability to measure meaningful change over time in preparation b.6 A major use of SASNOS is in repeated assessment, including tracking response to rehabilitation. However, in practice, determining when a score-difference on a standardised instrument indicates real change is difficult. Indeed, whilst many instruments have evidence confirming validity and reliability, information on responsiveness is less apparent. Some have none, or use aggregate data and tests of statistical significance, which do not translate obviously in interpreting difference scores for individual patients. There is also no agreement on one ‘gold standard’ method for determining responsiveness. The authors examine this issue in relation to the SASNOS, exploring multiple methods to determine responsiveness and present several indices to fit a range of applications. For clinical use they favour thresholds derived from the Standard Error of Measurement, which generates minimum score-difference values for SASNOS. This innovation gives clinicians confidence that higher scores on reassessment exceed variation attributable to error in the instrument and reflects ‘meaningful’ improvement for patients.

The final innovation is a revised SASNOS. All standardised assessments can be improved and should be continually reappraised and modified. Whilst feedback since 2011 has been extremely positive, the scope and number of items in the ‘communication’ domain can nevertheless be improved. Consequently, 30 new ‘communication’ items have been constructed and a study implemented to populate content of SASNOS-Revised (SASNOS-R). Whilst SASNOS was standardised using ratings from a sample of 100 neurologically healthy people, the current study will re-examine all the items by recruiting a much larger sample from the general population as well as collecting multiple ratings over time. Readers wishing to contribute to this important work can participate here: http://bit.ly/SASNOSsurvey. A further study will also collate SASNOS-R ratings from a larger sample of people with acquired and progressive neurological conditions than originally employed to fully determine usefulness of SASNOS-R.

References

- Kelly G, Brown S, Todd J, Kremer P. Challenging behaviour profiles of people with acquired brain injury living in community settings. Brain Injury 2008;22:457-470.

- Wood RLl, Alderman N, Williams C. Assessment of Neurobehavioural Disability: a review of existing measures and recommendations for a comprehensive assessment tool. Brain Injury 2008:22;905-918.

- Alderman N, Wood RLl, Williams C. The development of the St Andrew’s-Swansea Neurobehavioural Outcome Scale: validity and reliability of a new measure of neurobehavioural disability and social handicap. Brain Injury 2011;25:83-100.

- Alderman N. Effectiveness of neurobehavioural rehabilitation for young people and adults with traumatic brain injury and challenging behaviour. Advances in Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation 2011;11:26-27.

- Alderman N, Williams C, Wood RLl. When test scores in the normal range don’t equate to true independence: a method to convey the impact of context on ratings of neurobehavioural disability and social handicap using the ‘St Andrew’s – Swansea Neurobehavioural Outcome Scale’ (SASNOS). In preparation a.

- Alderman N, Williams C, Wood RLl. Measuring change in symptoms of neurobehavioural disability: responsiveness of the St Andrew’s – Swansea Neurobehavioural Outcomes Scale (SASNOS). In preparation b.