Headaches make up 30% of all Neurology outpatient consultations [1]. There is distinct variability in the management of headaches by Neurologists, leading to unnecessary disparities in the standard of care and likelihood of response between patients. A significant proportion of patients with headache diagnoses do not receive the evidence-based treatments recommended in national or international guidelines [2], and substantial numbers of patients are not receiving preventive therapies [3]. Ziegeler et al. found that a third of patients reporting to a tertiary headache centre had not received preventive therapy in line with guidelines, and half had never been prescribed a preventive treatment [2]. Considering that 46% of the global adult population are estimated to have a headache disorder [4], this lack of a consistent, evidence-based approach is somewhat incongruent with the patient socio-economic impact.

It is probable that lack of adherence to current headache guidelines is a multi-faceted issue. This variation in treatment (and therefore patient outcome), although unexplored [2], is not likely to be a simple educational issue. To add to this, an educational approach, in the form of seminars and workshops, does not have entirely positive evidence to support its use in implementing changes to patient care [5]. It seems more probable that there are also structural issues within the health service that in some way preclude patients with headache disorders from gaining appropriate care. For example, using only doctors to care for patients with such a common condition may cause bottle-necking in access, and may not be an appropriate use of clinical resource. The current context of a global pandemic has shown us the importance of using the skillsets of all NHS staff working together for patient care. For headache care this could involve greater use of nursing colleagues or allied health professionals such as Pharmacists.

To facilitate such an aim, an easily used and standardised approach is essential. We believe that the guidelines from the British Association for the Study of Headache (BASH) [6], could facilitate such an approach.

BASH Guidelines and the New Headache Management System

BASH published their latest guideline on the management of headache in 2019. The intent is to assist the clinician when seeing a patient in real time, and help allied health professionals in managing patients using a simple and standardised menu of care. The guideline is user friendly and logically structured, initially discussing the diagnostic process and how any clinician may recognise features of different primary headache disorders on initial presentation, as well as red flags and the role of imaging in a succinct fashion that can be easily communicated with patients. It then provides brief summaries of the principles and treatment options in migraine, medication-overuse headache, tension-type headache, and the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias.

All treatments recommended in the guideline have been consistently shown to be effective by good quality randomised placebo controlled trials, and are not included unless they have been considered to consistently have class A evidence and have been recommended in two or more of the NICE, SIGN, AHS, or EFNS guidelines. It has received accreditation from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, and national patient charities such as The Migraine Trust.

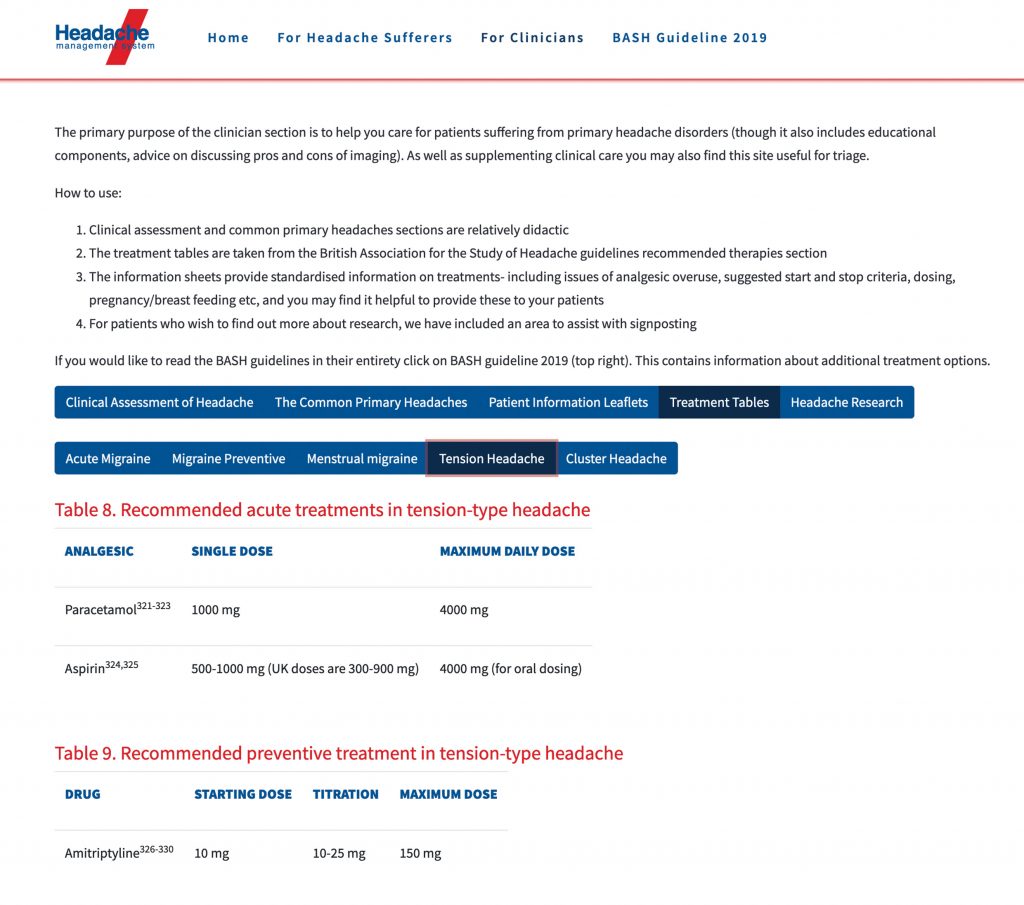

To further facilitate use of the 2019 guidelines, a national headache management system has also been developed (headache.org.uk).

The system can support allied health professionals in managing primary headache disorders in line with the latest BASH guidance. The tool can be simply accessed via headache.org.uk and will allow more effective facilitation of patient self-management.

After accessing the website, the tool is easy to navigate as both a patient and healthcare professional, with a flow chart type process to take both parties directly to their required information (Figures 1 and 2).

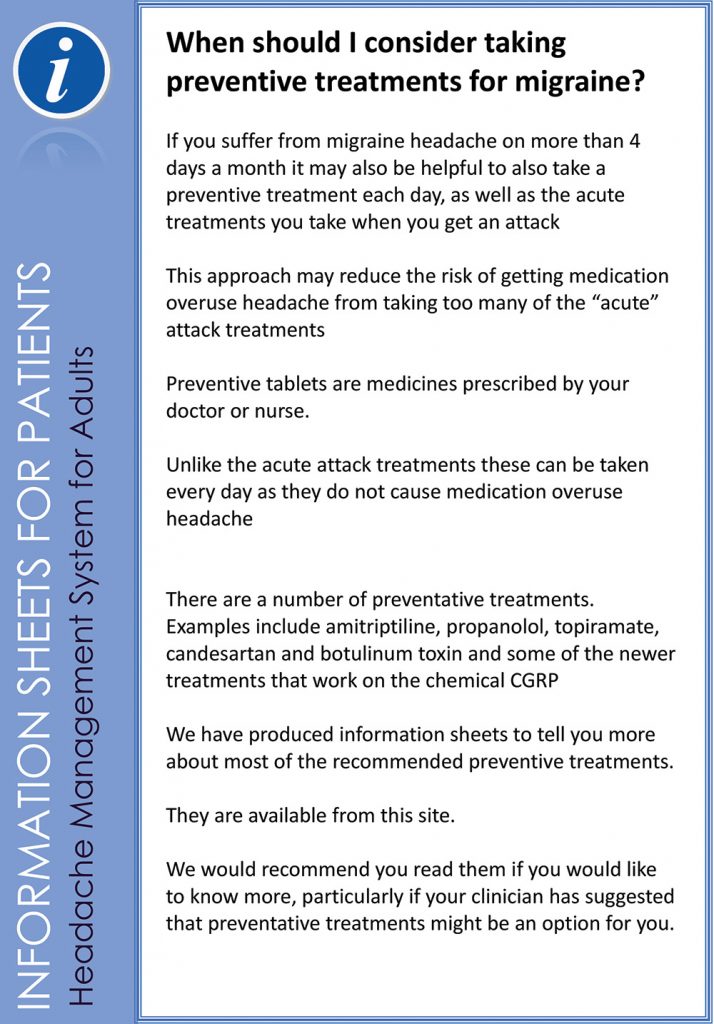

This avoids having to navigate a large amount of preamble beforehand, as is so often the case with guidelines. The included patient information area contains a number of downloadable patient information sheets that contain information consistent with the guidance in the section provided for healthcare professionals, as well as additional information on self-care strategies. An example of one such information sheet is shown in Figure 3.

Utilising this system will allow more consistent messaging between healthcare professionals. The use of patient information sheets and educational videos further allows a multimodal approach to patient information such that this can be tailored to individual communication need. Its readability means it could also be used as a learning tool for healthcare students to ensure people are trained to practice in line with the evidence base.

We envisage this having multiple benefits. Consistent messaging will improve adherence by reducing confusion for patients provided by conflicting information, and patients will have confidence that their ongoing self-care is being conducted in an evidence-based fashion. Adoption of a more systematic approach on a national level by a range of healthcare professionals across primary and secondary care settings will hopefully allow greater parity of care for patients, improving the statistics on inequitable treatment previously mentioned.

As the shape of training changes are introduced, with diversion of Neurology Trainees towards dual training in General Medicine and Neurology, it is inevitable that the result will be reduced experience in neurological conditions compared to their counterparts in the training model currently extant. It is possible that a more systematic approach to headache care will also be of assistance in this regard.

This system could also assist busy Neurology departments from a service provision perspective by making triage for patients with primary headache conditions more easily standardised and efficient.

Therefore, we are advocating for the integration of a headache management system into current services as a supplement to the usual process of care. This could help provide evidence-based care in a more efficient fashion, and also provide a more adaptable approach to service provision made requisite by the ongoing pandemic and incoming shape of training changes.

References

- NICE. SCOPE, NICE Clinical Guideline – Headaches: diagnosis and management of headaches in young people and adults. 2010.

- Ziegeler C, Brauns G, Jürgens TP, May A. Shortcomings and missed potentials in the management of migraine patients – experiences from a specialized tertiary care center. The Journal of Headache and Pain. 2019;20(1):86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1034-8

- Zebenholzer K, Andree C, Lechner A, Broessner G, Lampl C, Luthringshausen G, et al. Prevalence, management and burden of episodic and chronic headaches–a cross-sectional multicentre study in eight Austrian headache centres. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:531. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-015-0531-7

- Stovner L, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):193-210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x

- Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1

- British Association for the Study of Headache. BASH Guidelines 2019 http://www.bash.org.uk/guidelines/: British Association for the Study of Headache (BASH); 2019.