Abstract

A growing body of evidence exists advocating the value of physical activity and exercise for people with Parkinson’s. Such is the importance of being active, participation in exercise is perceived to be of equal importance to medication in the long-term management of Parkinson’s. Despite a substantial body of evidence, the optimal prescription of exercise or mode of delivery remains underdetermined. This article aims to discuss the current evidence and provide guidance of prescription of exercise during each of three commonly-referred to stages of Parkinson’s: newly diagnosed, maintenance and complex.

Parkinson’s is the fastest growing neurological condition, with a 50% predicted rise of people living with the condition by 2030 [1]. In the absence of a cure, interventions that aim to limit the rate of decline and promote quality of life are of paramount importance to researchers and clinicians alike. Interest in the value of physical activity (PA), including exercise, has grown exponentially due to its potential neurorestorative role, as well as its positive impact on slowing the rate of decline. It is therefore essential that all members of the multi-disciplinary team are aware of the benefits of both for people with Parkinson’s and can promote participation in activity by signposting individuals to local PA opportunities. This paper summaries the PA evidence and describes PA prescription of each of three commonly-referred to stages of Parkinson’s: newly diagnosed, maintenance and complex.

Physical activity is an umbrella term which encompasses bodily movements produced by skeletal muscles, including a wide range of behaviours like gardening, housework and leisure-related activities [2]. Exercise is a subcategory of physical activity, defined as activities which are planned, structured, and purposeful, with the intention of improving and/or maintaining one or more components of physical fitness [3]; the terms Exercise and Physical activity however are commonly used interchangeably and inconsistently in activity-based research.

Diagnostic stage

PA should form an integral part of Parkinson’s management from diagnosis, and should be perceived as of equal importance to medication, not as complementary [4]. Owing to the heterogeneous nature of Parkinson’s, a personalised approach to PA is advocated [5]. Key messages at this stage are to promote a physically active focused lifestyle, supported by friends and the Parkinson’s community, to support the development of a long-term activity habit. Exercise should be prescribed in tandem with contextualised education, to support changes in physical activity behaviour, and to provide people with Parkinson’s with the knowledge and skills to self-manage their physical activity.

When prescribing physical activity, frequency, intensity, type of activity and time need to be carefully considered. Within the diagnostic phase exercise prescription should focus on supporting people with Parkinson’s to develop a regular physical activity habit of a minimum of 2.5 hours a week [6], developing confidence to participate in higher intensity exercise is also advocated at the early stages of Parkinson’s. Participation in moderate to high intensity exercise (65-85% of mHR) has been shown to be both safe and feasible for people with Parkinson’s [7] and is associated with potential neurorestorative effects. Animal studies and a small number of human-based studies have demonstrated that high intensity exercise promotes improved vascularisation through angiogenesis, as well as increased concentration of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF or GDNF which are essential for neuronal growth, and integrity [5]. 150 minutes of moderate to high intensity exercise is advocated such as Nordic walking, aerobics, and cycling each week.

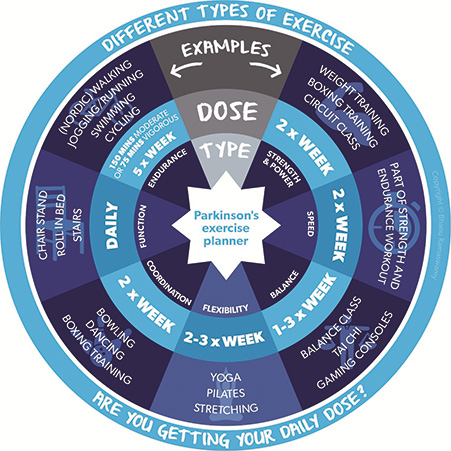

Types of exercise should be varied reflecting the range of motor and non-motor symptoms that people present with, combined with individual preferences. Reflecting current guidelines, strength training should be undertaken two to three times a week targeting spinal, hip and knee extensors and ankle dorsiflexors, prescribed in a progressive manner, where both resistance and task complexity are incrementally increased [8]. Flexibility training should be undertaken twice a week focusing on the spine, upper and lower limbs, ensuring that amplitude of movement is maintained during functional tasks [4]. Similarly, balance training should be conducted twice weekly including turning, and dynamic movements incorporating progressive dual and cognitive tasks [8]. Figure 1, the exercise wheel acts as a guide on the frequency and types of exercise to guide physical activity engagement.

Maintenance stage

Following on from the diagnosis stage, it remains important to continue with general PA and advice in the maintenance stage to keep the person fit and active for as long as possible. Progression of the condition can reduce physical capacity and mobility, which can lead to inactivity; these issues can be improved with exercise [8] but it is also important to recognise that they make exercising more challenging. Increasing severity of motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, compromising joint range of movement and strength, and the combined effects of rigidity and tremor alter the biomechanics of movement and impair balance. Collectively these symptoms reduce PA levels which can lead to muscle atrophy, joint stiffness, and reduced physical capacity.

It is also important to remember the influence of other conditions and non-motor symptoms including apathy, fatigue, pain and fear of falling which may become more problematic in this phase. Recognising these increasing barriers to exercise [4] emphasises the importance of addressing motivation and using a person-centred approach [5,9,10]. Creating a routine is very important when establishing consistent PA behaviour, but as symptoms may become a little more unpredictable it may be important to have options so the individual always has a manageable exercise plan relevant to how they feel.

While the principles of PA introduced in the diagnosis phase remain important, the approach used to achieve this may need to be adapted. Parkinson’s specific programmes which address motor and non-motor symptoms more explicitly may be helpful [11]. Individuals should be supported to maintain or increase their level of activity and to engage with activities which target flexibility and focus on posture and balance. The individual should be supported to maintain the effort with which they are active while also ensuring that body and mind are engaged so as to preserve memory, attention and learning and to aid the management of non-motor symptoms such as sleep and mood. Exercise professionals should be aware that motor symptoms can put individuals at risk of injury so care should be taken to prepare individuals appropriately for PA. Activity should be conducted when medication is optimised and it is important to regularly review and adapt the PA programme.

Later stage

The longer a person has Parkinson’s, interventions should combine exercise, movement strategies and cues so they can function even when in the ‘off’ state [12]. In the later stages of Parkinson’s, co-morbidities increase and people reduce physical activity and exercise performance levels, which have been associated with higher rates of all-cause mortality [13].

Little quantitative research exists to demonstrate the benefits of continuing exercise past Hoehn and Yahr Phase 3 due to the increasing complexity of the condition, however, the lived experience of people with Parkinson’s repeatedly illustrates the importance of maintaining an exercise routine for both physical and mental health, particularly if unable to access their usual programmes [14].

The people with Parkinson’s and those supporting them, who contributed towards the development of the Parkinson’s UK Exercise Framework spoke of the difficulties in maintaining a sufficient dosage of exercise to manage physical challenges as their condition progressed, but some exercise was viewed as essential in preserving fitness and functional daily activities where possible and managing the discomfort from likely postural changes [15]. Alterations to physical and mental ability necessitate an emphasis on increased support from others to assist the person with Parkinson’s with exercise, particularly for transfers and gait related activities [16]. As mobility impairments compromise safety, exercise should become more chair based using free weights and stationery equipment e.g. pedallers, plus be supervised to a greater extent [17].

Whilst still adhering to the Parkinson’s-specific principles of exercising at maximal effort, amplitude and power, attention should be paid to the following:

- Ensuring that functional movement is a key component of exercise routines e.g. sit to stand, turning in bed, overcoming episodes of freezing – all of which may need additional training of movement strategies or cuing techniques.

- Respiratory complications are the highest cause of mortality in people with Parkinson’s. As bradykinesia and rigidity affect lung function [18], respiratory exercises should be added to any exercise routine [19].

Conclusion

Physical activity should form an integral part of the management of people with Parkinson’s from diagnosis. Like medication, physical activity prescription needs to reflect individual needs, and should encompass strength, flexibility, balance, aerobic, and functional based exercise. Physical activity should be prescribed in parallel with contextualised education to provide the person with adequate knowledge and skills to develop a sustained physical activity habit.

References

- Dorsey R, Sherer T, Okun M, Bloem B. The emerging evidence of the Parkinson pandemic. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. 2018;8(Suppl 1):10.3233/JPD-181474 https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-181474

- World Health Organisation. (2020). Physical activity Guidleines. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 (Accessed March, 2022)

- Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public health reports. 100;(2):126-131.

- Keus S, Munnke, M, Graziano M, Paltama J, Pelosin E, Domingos J, Bruhlmann S, Ramaswamy B, Priris J, Struicksma C, Rochester L, Nieuwboer A, Bloem B. On behalf of the guideline development group. (2014). European Physiotherapy Guideline for Parkinson’s Disease. KNGP/ParkinsonsNet, The Netherlands.

- Ellis T, Rochester L. Mobilising Parkinson’s disease: the future of exercise. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. 2018;8(s1):S95-S100. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-181489

- Rafferty MR, Schmidt PN, Luo ST, Li K, Marras C, Davis TL, Guttman M, Cubillos F, Simuni T; and all NPF-QII Investigators. Regular Exercise, Quality of Life, and Mobility in Parkinson’s Disease: A Longitudinal Analysis of National Parkinson Foundation Quality Improvement Initiative Data. Journal of Parkinsons Disease. 2017;7(1):193-202. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-160912

- Schenkman M, Moore C, Kohrt W, Hall D, Delitto A, Comella C, Josbeno D, Christiansen C, Berman B, Kluger B, Melanson E, Jain S, Robichaud J, Poon C, Corcos D. Effect of High-Intensity Treadmill Exercise on Motor Symptoms in Patients With De Novo Parkinson Disease: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurology. 2018; 75(2):219-226. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3517

- Radder DLM, Nonnekes J, van Nimwegen M, Eggers C, Abbruzzese G, Alves G, Browner N, Chaudhuri KR, Ebersbach G, Ferreira JJ, Fleisher JE, Fletcher P, Frazzitta G, Giladi, Guttman M Iansek R, Khandhar S, Klucken J, Lafontaine AL, Marras C, Nutt J, Okun MS, Parashos SA, Munneke M, Bloem, BR. Recommendations for the Organization of Multidisciplinary Clinical Care Teams in Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. 2020;10(3):1087-1098. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-202078

- Ramaswamy B, Jones J, Carroll, C. Exercise for people with Parkinson’s: a practical approach. Practical Neurology. 2018;18:399-406.https://doi.org/10.1136/practneurol-2018-001930

- Hunter H, Lovegrove C, Haas B, Freeman J, Gun, H. Experiences of people with Parkinson’s disease and their views on physical activity interventions: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 2019. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003901

- McDonnell M, Rischbieth B, Schammer T, Seaforth C, Shaw A, Philips A. Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT-BIG) to improve motor function in people with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2017;32(5):607-618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215517734385

- Okada Y, Ohtsuka H, Kamata N, Yamamoto S, Sawada M, Nakamura J, Okamoto M, Narita M, Nikaido Y, Urakami H, Kawasaki T, Morioka S, Shomoto K, Hattori, N. Effectiveness of Long-term physiotherapy in Parkinson’s disease: A Systematic review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. 2021;11:1619-1630. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-212782

- Yoon SY, Suh JH, Yang SY, Han K, Kim YW. Association of physical activity, including amount and maintenance, with all-cause mortality in Parkinson’s disease. JAMA Neurology. 2021;78(12):1446-1453. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3926

- Simpson J, Eccles F, Doyle, C. The impact of Coronavirus restrictions on people affected by Parkinson’s: The findings from a survey by Parkinson’s UK. Lancaster University and Parkinson’s UK. 2020. Accessed on 9th Dec 2021. https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-07/Parkinson%27s%20UK%20Covid-19%20full%20report%20final.pdf

- Parkinson’s UK Exercise Framework (2017): https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/professionals/exercise-framework-professionals (last accessed Jan 2022)

- Rukavina K, Batzu L, Boogers A, Abundes-Corona A, Bruno V, Chaudhuri RK. Non-motor complications in late stage Parkinson’s disease: recognition, management and unmet needs. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2021;21(3):335-352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2021.1883428

- Borchers EE, McIsaac TL, Bazan-Wigle J, Elkins AJ, Bay RC, Farley BG. A physical therapy decision-making tool for stratifying persons with Parkinson disease into community exercise classes. Neurodegenerative Disease Management. 2019;9(6):331-346. https://doi.org/10.2217/nmt-2019-0019

- Dos Santos RB, Fraga AS, de Sales Corioilano MDGW, Tiburtino BF, Linsm OG, Esteves ACF, Asano, NMJ. Respiratory muscle strength and lung function in the stages of Parkinson’s disease: Journal Brasilerio de Pneumonologia. 2019;45(6) https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-3713/e20180148

- van de Wetering-van Dongen VA, Kalf JG, van der Wees PJ, Bloem BR, Nijkrake MJ. The Effects of Respiratory Training in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. 2020;10(4):1315-133. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-202223