Abstract

Piriformis* syndrome is a subgroup of the deep gluteal syndrome, an important differential diagnosis of sciatica. Piriformis is a short external rotator muscle of the hip joint passing close to the sciatic nerve as it passes through the great sciatic foramen. The compression causes numbness, ache, or tingling in the buttocks, posterolateral aspect of the leg, and foot. The causes of sciatic nerve entrapment in the deep gluteal syndrome are best shown by endoscopic exploration. The frequency of anatomical variants in normal subjects, however, should caution that such anomalies are not necessarily the cause of symptoms.

Most people have experienced a transient dead numb leg after sitting awkwardly or for too long on a toilet seat or hard chair. This is perhaps a benign variant of the deep gluteal syndrome [1]. It is caused by compression or irritation of the sciatic nerve located within or adjacent to the greater sciatic notch [2]. Piriformis syndrome is a subgroup of the deep gluteal syndrome, first described by Yeoman in 1928 as sciatica caused by arthritis of the sacroiliac joint, the piriformis muscle and the adjacent branches of the sciatic nerve [3]. Other causes of entrapments within the subgluteal space are fibrous and vascular (inferior gluteal artery) bands, obturator internus/gemellus syndrome, and ischio-femoral pathology [4]. Before endoscopic exploration, the validity of this diagnostic label was uncertain since there were then no definite criteria and no specific tests, though many had been proposed (qv). In a paper of 18 studies and 6,062 cadavers the prevalence of piriformis and sciatic nerve anomalies in cadavers was 16.9%; almost identical to 16.2% in the ‘surgical cases’ [5].

Anatomy

The piriformis muscle is a short external rotator muscle of the hip joint that is stretched with internal rotation of the leg. H. Crooke described it in 1615 as:

The fourth extender called Iliacus externus piriformis, the outward hanch peare muscle …because it filleth the outward and lower cavity of the hanch bone with his oblique position, and is like a round peare.

(Oxford English Dictionary)

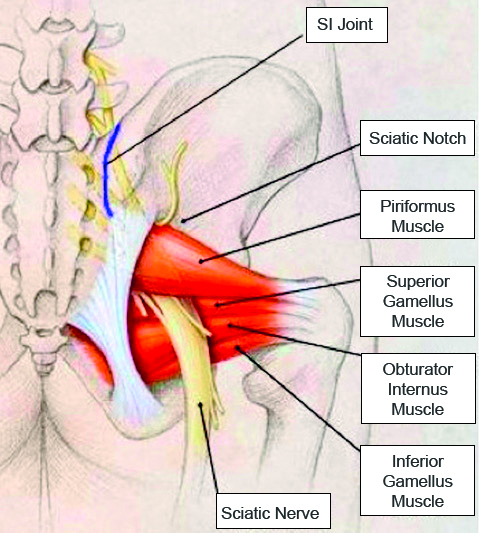

Its origin is from the anterior surface of the sacrum; it inserts into the greater trochanter via a tendon that is merged with tendons of the obturator internus and gemelli muscles. The sciatic nerve passes out of the pelvis through the great sciatic foramen, usually below the piriformis. (Figure 1) There are several anatomical variations of the relationship between the piriformis muscle and sciatic nerve, which may conduce to irritation, or entrapment of the nerve [6]. The undivided nerve may pass below or through the piriformis or, it may divide above piriformis into the tibial and lateral popliteal nerves with one portion exiting through piriformis, the other inferior to it.

Clinical features

As a differential diagnosis of sciatica caused by the much more common disk lesions the piriformis syndrome is characterised by buttock numbness or pain that occurs after prolonged sitting [6,7] on a wallet, cycling, or by excessive or repeated exercise [9]. Back pain is not a feature. Most often a mild numbness, ache or tingling in the buttocks, posterolateral aspect of the leg and foot subside after a few minutes in the erect posture or walking.

In less frequent but more severe cases symptoms are persistent. Typical but not diagnostic physical signs are:

- an antalgic posture – sitting on the other ‘cheek’ with the affected thigh adducted and internally rotated.

- hip flexion, adduction and internal rotation (FAIR) narrow the space between the inferior border of the piriformis, superior gemellus and sacrotuberous ligament which may induce pain.

- pain experienced during forceful internal rotation of the extended thigh (Freiberg sign).

- pain on resisted abduction and external rotation of the hip in a flexed/sitting position (Pace sign). Local tenderness on palpation is variable and pain on straight leg raising is commonly absent.

Investigations

In an MRI study of 783 cases, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of piriformis syndrome, buttock pain, or sciatica between normal and variant sciatic nerve anatomy [10]. The piriformis syndrome is probably overdiagnosed [5,11]. Only if symptoms are persistent or disabling should investigations be used to exclude discogenic lumbosacral root compression, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, spinal, paraspinal, and pelvic masses.

In such instances investigations are useful but none are diagnostic. The causes of sciatic nerve entrapment in the deep gluteal region are best shown by endoscopic exploration. The main use of MRI is to exclude lumbosacral spinal aetiologies. MRI may be normal or show hypertrophy/atrophy, fibrosis, or anomalous insertion of the piriformis. MR neurography can show piriformis muscle asymmetry and sciatic nerve hyperintensity at the sciatic notch [12]. Increased H-reflex latency in nerve conduction studies and electromyographic denervation in muscles innervated by the sciatic nerve are variably recorded but unreliable.

The study of Han et al [13] after exclusion of other spinal or pelvic pathology proposed diagnostic criteria. (Table 1). The frequency of anatomical variants in normal subjects, however, should caution that such anomalies are not necessarily the cause of symptoms.

| Table 1. Proposed diagnostic features [13] |

| Deep-seated buttock pain with radiating pain, especially intolerable sitting pain Tenderness of the piriformis muscle Positive provocative test: Freiberg’s test, Pace test Positive findings on CT or MRI: asymmetry or enhancement around the sciatic nerve Pain relief with a local anaesthetic or steroid injection |

| Piriformis syndrome is diagnosed if 4 or more criteria are present |

Treatment

Most instances are benign and self-limiting if provocative factors are avoided. A bewildering variety of treatments have been used, many with imperfectly controlled studies, most claiming high success rates. They include: anti-inflammatory drugs, physiotherapy, piriformis stretching [14], injection of local anaesthetics or corticosteroids, and botulinum toxin injections [15]. Periarticular endoscopic decompression of the sciatic nerve [4,16], is less invasive than exploratory surgery and in intractable cases is useful in clarifying the varied causes of the deep gluteal syndrome and in affording means for correcting causal lesions. Thirty-nine of 52 patients had good to excellent outcomes in a review in 2016 [4]. Muscle resection with or without neurolysis of the sciatic nerve should be the last resort but was deemed “satisfactory in 10 of 12 patients who had failed to respond to more conservative treatments.” [13]

*Sometimes spelt pyriformis

References

- Hernando MF, Cerezal L, Pérez-Carro L. et al. Deep gluteal syndrome: anatomy, imaging, and management of sciatic nerve entrapments in the subgluteal space. Skeletal Radiol 2015;44:919-934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-015-2124-6

- Robinson D R. Piriformis Syndrome in Relation to Sciatic Pain. Am J Surg 1947;73(3):355-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(47)90345-0

- Yeoman W. The relation of arthritis of the sacro-iliac joint to sciatica, with an analysis of 100 cases. Lancet. 1928;2:1119-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)84887-4

- Carro LP, Hernando MF, Cerezal L, Navarro IS, Fernandez AA, Castillo AO. Deep gluteal space problems: piriformis syndrome, ischiofemoral impingement and sciatic nerve release. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2016;6(3):384-396. https://doi.org/10.32098/mltj.03.2016.16

- Smoll NR. Variations of the piriformis and sciatic nerve with clinical consequence: a review. Clin Anat. 2010;23(1):8-17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.20893

- Beaton LE, Anson BJ. The relation of the sciatic nerve and its subdivisions to the piriformis muscle. Anat Record 1937;70:1-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.1090700102

- Rodrigue T, Hardy RW. Diagnosis and treatment of piriformis syndrome. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2001;12(2):311-319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1042-3680(18)30056-1

- Byrd JW. Piriformis syndrome. Oper Tech in Sports Med 2005;13:71-79. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.otsm.2004.09.008

- Lutz E.G. Credit-card-wallet sciatica. JAMA 1978;240(8):738. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1978.03290080028012

- Bartret AL, Beaulieu CF, Lutz AM. Is it painful to be different? Sciatic nerve anatomical variants on MRI and their relationship to piriformis syndrome. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(11):4681-4686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5447-6

- Stewart JD. The piriformis syndrome is overdiagnosed. Muscle Nerve 2003;28(5):644-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.10483

- Filler AG, Haynes J, Jordan SE, et al. Sciatica of nondisc origin and piriformis syndrome: diagnosis by magnetic resonance neurography and interventional magnetic resonance imaging with outcome study of resulting treatment. J Neurosurg Spine 2005;2(2):99-115. https://doi.org/10.3171/spi.2005.2.2.0099

- Han SK, Kim YS, Kim TH, Kang SH. Surgical Treatment of Piriformis Syndrome. Clin Orthop Surg 2017;9(2):136-144. https://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2017.9.2.136

- Fishman LM, Dombi GW, Michaelsen C, Ringel S, Rozbruch J, Rosner B, Weber C. Piriformis syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome-a 10-year study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002;83:295-301.https://doi.org/10.1053/apmr.2002.30622

- Fishman LM, Wilkins AN, Rosner B. Electrophysiologically identified piriformis syndrome is successfully treated with incobotulinum toxin a and physical therapy. Muscle Nerve 2017;56(2):258-263. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25504

- Park M, Yoon S, Jung S. et al. Clinical results of endoscopic sciatic nerve decompression for deep gluteal syndrome: mean 2-year follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:218. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1062-3.