Abbreviations

CNS – central nervous system; CSF – cerebrospinal fluid; DMT – disease-modifying therapy; GA – glatiramer acetate; IFNb – interferon beta; MS – multiple sclerosis; MSer* – someone with MS; MSers* – a group of people with MS; RR – relapsing remitting; SP – secondary progressive; PP – primary progressive

What term do you use to refer to someone with MS?

MSer (noun) – someone with MS, MSers (plural) – group of people with MS.

To the best of my knowledge the term MSer was first used on the social network site shift.ms (www.shift.ms), for young people with MS. A subsequent survey conducted on our multiple sclerosis research blog (www.ms-res.org) amongst people with MS revealed that MSer is the preferred term that people with MS would like to be referred to when addressed either as individuals (MSer) or as a collective group (MSers). MSer was preferred to the terms MS’er, which is the abbreviation for MS sufferer, patient, client or person with MS.

Introduction

MS is the commonest non-traumatic disabling disease to affect young adults in the UK. Although current dogma states that it is an organ-specific autoimmune disease of the central nervous system the antigenic targets of the autoimmune attack have yet to be identified. Despite the cause of MS remaining undefined there is an increasing understanding of the causal pathways that underlie the disease. MS is considered by most to be a complex disease due to an interaction between genetic and environmental factors [1].

Clinical course

The clinical phenotype of MS is heterogeneous and determines the clinical classification of the disease [2]. Approximately 85% of MSers in the UK present with attack onset disease that follows a relapsing-remitting (RRMS) course that in the pre-DMT era became secondary progressive (SPMS) in the majority of MSers (65-80%) [3]. Whether this latter figure remains as high as this in the post-DMT era is unknown at present; it is unclear whether or not DMTs delay or in some cases prevent the onset of the secondary progressive phase of MS. A minority of patients (15%) have a progressive course from outset and are referred to as having primary progressive MS (PPMS) [5]. The average age of onset of relapsing MS is between 28 and 31 years of age with a median time to the onset of SPMS of approximately 10 years. Interestingly the average age of onset of PPMS coincides with the age of onset of the secondary progressive phase of ~38-40 years of age. Importantly, the clinical courses of MS in the SP and PP phases are indistinguishable [5]. When followed longitudinally anything from 5-25% of PPMSers go on to have superimposed relapses and are referred to as having progressive-relapsing MS (PRMS) [2]. Often MSers presenting with a PPMS-type course are found on detailed enquiry to have had a prior sentinel event compatible with a demyelinating attack; this typically occurs decades before the onset of disease progression. These MSers have been referred to in the past as having transitional MS [6], however, the current Lublin and Reingold classification categorises these MSers as having SPMS [2]. Why bother with a detailed clinical classification? It turns out that relapses, and the presence of gadolinium(Gd)-enhancing lesions on MRI, predict a therapeutic response to currently licensed disease-modifying therapies, or more broadly anti-inflammatory drugs. MSers with relapses and/or focal Gd-enhancing MRI activity indicative of focal inflammation respond to DMTs and this probably applies to PPMSers [7].

Differential diagnosis

The majority of PPMSers present with a progressive spastic paraparesis. However, several other well-defined primary progressive phenotypes have been described including a progressive cerebellar syndrome, progressive optic atrophy and progressive hemispheric or subcortical pseudotumoral presentation. Important conditions that can mimic PPMS that need to be considered in the differential diagnosis are neurosarcoidosis, HTLV1-associated myelopathy, adrenomyeloneuropathy and Sjögren’s myelopathy. Sjögren’s myelopathy is not a well-defined clinicopathological entity and may simply represent an association between Sjögren’s syndrome and PPMS [9].

Pathogenesis

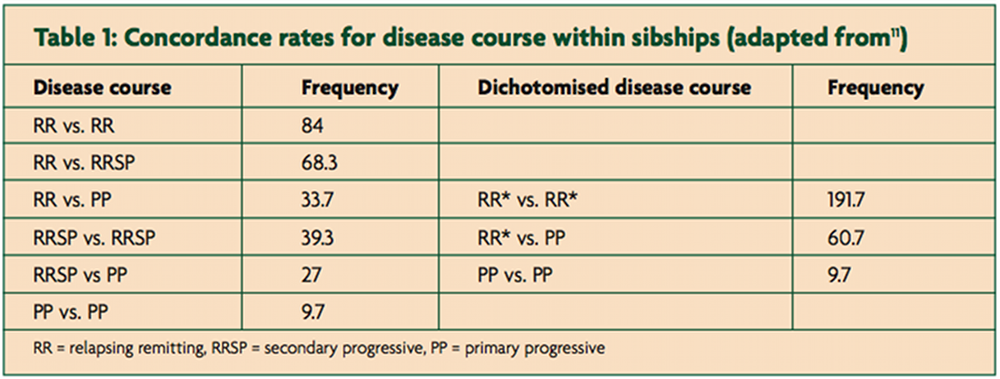

Is PPMS a different disease to relapse onset disease? This is unlikely for several reasons. Firstly, PPMSers are as likely to be positive for major at risk HLA-DRB1*15.01 as MSers with relapse-onset disease [10]. Secondly, in sibling pairs concordant for MS only 50% are concordant for clinical course (see Table 1) [11].

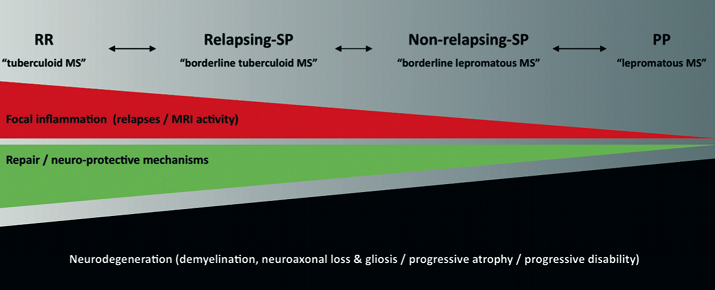

If RR and PPMS were different diseases you would expect the disease course to be concordant between siblings. Finally, pathological studies have not been able to differentiate relapse-onset from a primary progressive MS [12,13]. Although there are a smattering of publications suggesting quantitative immunological differences between PPMS and relapse-onset MS; however, none of the findings are robust enough to make definitive claims. I therefore believe that PPMS and relapse-onset disease are part of the same spectrum and what determines whether or not someone has relapses depends on qualitative differences in the type of inflammatory response that occurs within the central nervous system in response to whatever is causing or triggering the disease. I have previously proposed that the MS spectrum is not dissimilar to what is seen with regard to the clinical course or phenotype in leprosy [14]; with relapsing MS, characterised by well circumscribed areas of focal inflammation, being referred to as tuberculoid MS and PPMS, with more low grade chronic inflammation, being referred to as lepromatous MS and a spectrum between them (Figure 1). To test this hypothesis the inciting antigens, be they autoimmune or not, need to be defined.

Epidemiology of PPMS

The epidemiology of PPMS is not dissimilar to that of relapse-onset disease with the exception that PPMS is very rare in children, occurs more frequently in males and its incidence seems to be relatively static. The female to male ratio is generally 1:1 with regard to PPMS and 2 or even 3:1 for relapse onset disease. The increasing female preponderance of MS, as seen by changes in the sex ratio, seems to be driven by relapse-onset disease, with the incidence of PPMS remaining relatively constant [15].

Diagnostic criteria

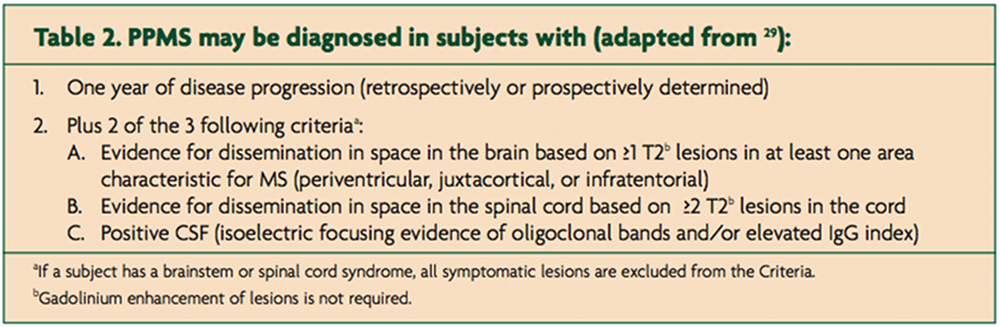

PPMS is diagnosed using the same principles as relapse-onset disease; you have to demonstrate dissemination in time and space and exclude other potential causes [16]. The original McDonald diagnostic criteria required an abnormal or positive CSF examination, as an absolute requirement, to make a diagnosis of PPMS [17]; a positive CSF was defined as intrathecal oligoclonal IgG bands and/or a raised IgG index. These criteria were subsequently changed so that a diagnosis of PPMS could be made with a normal CSF examination (Table 2).

These changes were prompted by finding that 189/938 (20%) subjects in the glatiramer acetate in PPMS study (PROMiSe study) had a normal CSF study [18]. The PROMiSe Study was subsequently terminated early due to a lack of efficacy; interestingly in this study the CSF negative group had a more benign course that the CSF positive cohort (Jerry Wolinsky, personal communication). This would imply that CSF negative PPMS is not the same disease as CSF positive PPMS and is a strong argument for reinstating the original McDonald criteria for PPMS. In fact, two contemporary clinical trials in PPMS require an abnormal CSF as an inclusion criteria [19,20] which is a vote of no confidence for the current criteria.

Treatment

Unfortunately, no clinical trials of licensed MS DMTs have shown an impact on the course of PPMS; both interferon beta [21,22] and glatiramer acetate [23] trials have been negative. Recently, however, during the five-year period without treatment after termination of the two-year clinical trial of interferon beta-1b for the treatment of PPMS [22], the interferon beta-1b group had better 9-hole-peg-test, word list generation test scores and magnetisation transfer ratios in the normal-appearing white matter than subjects treated with placebo [24].The placebo group also showed a greater decrease in brain volume over the seven years of observation than the actively treated subjects [24]. These observations led the investigators to suggest that immunomodulation should not be abandoned as a possible treatment for PPMS and augurs well for two large phase 3 studies of fingolimod [19] and ocrelizumab (anti-CD20) [20] in PPMS. Fingolimod is an oral, small molecule, sphingosine phosphate-1 (SP1) receptor modulator that traps lymphocytes in lymph nodes and may have direct neuroprotective effects with the CNS. Fingolimod has recently been licensed for the treatment of RRMS [25]. Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody and ocrelizumab a humanised monoclonal antibody, that both deplete B-cells by targeting CD20 on the surface of B cells. The ocrelizumab (anti-CD20) PPMS study [20] is a follow-on of the phase 2 rituximab in PPMS study [26]; this was a 96 week study that randomised 439 PPMSers, in a 2:1 ratio, to receive either two 1,000 mg intravenous doses of rituximab or placebo infusions every 24 weeks. Although there were no differences in time to confirmed disability progression on the EDSS between rituximab and placebo, a subgroup analysis showed that the time to confirmed disability progression was delayed in rituximab-treated PPMSers less than 51 years of age, in those with Gd-enhancing lesions on MRI and in those aged less than 51 years with Gd-enhancing lesions compared with placebo.

PPMSers are subject to a similar array of symptoms that relapse-onset MSers suffer from. However, PPMSers are particularly prone to spinal cord disease, typically progressive spastic paraparesis with increasing walking difficulties due to weakness and spasticity, sphincter involvement and myelopathic pain. There are recent developments regarding symptomatic treatments you should be aware of including the licensing of an oromucosal mouth spray containing a fixed ratio of the cannabinoids, tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol, for treating MS-related spasticity [27] and fampridine, a slow-release formulation of 4-aminopyridine, to improve walking speed in MSers [27]. Both these drugs have yet to be reviewed by NICE, therefore their availability for PPMSers under the NHS is limited at present.

Conclusion

Although PPMS is relatively uncommon it remains a significant clinical problem both diagnostically and therapeutically. PPMS is almost certainly part of the MS spectrum and there is no clinicopathological evidence to support PPMS as being a separate disease. Unfortunately, there are no licensed DMTs that have been shown to modify the course of PPMS. Despite this there is some emerging evidence that PPMS may respond to immunomodulatory therapies. Two large phase 3 trials are currently underway to test this hypothesis.

References

- Ramagopalan SV, Dobson R, Meier UC, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis: risk factors, prodromes, and potential causal pathways. The Lancet Neurology [Internet] 2010;9(7):727-39. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70094-6

- Lublin FD, Reingold SC. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology [Internet] 1996;46(4):907-11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8780061

- Weinshenker BG, Bass B, Rice GP, et al. The Natural History of Multiple Sclerosis: a Geographically Based Study. Brain [Internet] 1989;112(1):133-46. Available from: http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.1093/brain/112.1.133

- Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, et al. A geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. 2010;1914-29.

5, Cottrell D, Kremenchutzky M, Rice GP, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. 5. The clinical features and natural history of primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain?: a journal of neurology [Internet] 1999;122 ( Pt 4:625-39. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10219776 - Stevenson VL, Miller DH, Rovaris M, et al. Primary and transitional progressive MS: a clinical and MRI cross-sectional study. Neurology [Internet] 1999 [cited 2012 Jun 5];52(4):839-45. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10078736

- Hawker K, O’Connor P, Freedman MS, et al. Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Annals of neurology [Internet] 2009 [cited 2012 Mar 13];66(4):460-71. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19847908

- Seze JD, Devos D, Castelnovo G, Labauge P, Dubucquoi S. The prevalence of Sjogren syndrome in patients with primary progressive. 2001;1359-63.

Giovannoni G, Thorpe J. Is it multiple sclerosis or not? Neurology [Internet] 2001;57(8):1357-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11673570 - Martinelli-Boneschi F, Esposito F, Brambilla P, et al. A genome-wide association study in progressive multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) [Internet] 2012 [cited 2012 Mar 30];Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22457343

- Chataway J. Multiple sclerosis in sibling pairs: an analysis of 250 families. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry [Internet] 2001 [cited 2012 May 2];71(6):757-61. Available from: http://jnnp.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/jnnp.71.6.757

- Lucchinetti C, Brack W, Parisi J, Scheithauer B, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Annals of neurology [Internet] 2000;47(6):707-17. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10852536

- Revesz T, Kidd D, Thompson a J, Barnard RO, McDonald WI. A comparison of the pathology of primary and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain: a journal of neurology [Internet] 1994;117 Pt 4:759-65. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7922463

- Giovannoni G. The Yin and Yang of Inflammation in Multiple Sclerosis. In: Hommes OR, editor. Early Indicators Early Treatments Neuroprotection in Multiple Sclerosis. Milan: Springer Milan; 2004. p. 181-9.

- Koch-Henriksen N, Sorensen PS. Why does the north-south gradient of incidence of multiple sclerosis seem to have disappeared on the northern hemisphere? Journal of the neurological sciences [Internet] 2011 [cited 2012 Jun 5];311(1-2):58-63. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21982346

- Gafson A, Giovannoni G, Hawkes CH. The diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: From Charcot to McDonald. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders [Internet] 2012 [cited 2012 May 2];1(1):9-14. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/ pii/S2211034811000058

- McDonald WI, Compston a, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Annals of neurology [Internet] 2001;50(1):121-7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11456302

- Wolinsky JS. The diagnosis of primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Journal of the neurological sciences [Internet] 2003;206(2):145-52. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18431323

- Novartis. FTY720 in Patients With Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials [Internet]. 2008;:NCT00731692. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00731692?term=NCT00731692&rank=1

- Roche H-L. A Study of Ocrelizumab in Patients With Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials [Internet]. 2010; Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01194570?term=NCT01194570&rank=1

- Leary SM, Miller DH, Stevenson VL, Brex P a, Chard DT, Thompson a J. Interferon beta-1a in primary progressive MS: an exploratory, randomized, controlled trial. Neurology [Internet] 2003;60(1):44-51. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12525716

- Montalban X, Sastre-Garriga J, Tintore M, et al. A single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1b on primary progressive and transitional multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) [Internet] 2009 [cited 2012 Jun 5];15(10):1195-205. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19797261

- Wolinsky JS, Narayana P a, O’Connor P, et al. Glatiramer acetate in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a multinational, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Annals of neurology [Internet] 2007 [cited 2012 Apr 1];61(1):14-24. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17262850

- Tur C, Montalban X, Tintore M, et al. Interferon ?-1b for the treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis: five-year clinical trial follow-up. Archives of neurology [Internet] 2011 [cited 2012 Jun 5];68(11):1421-7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22084124

- Kappos L, Antel J, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod (FTY720) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. The New England journal of medicine [Internet] 2006;355(11):1124-40. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21727148

- Hawker K, Connor PO, Freedman MS, et al. Rituximab in Patients with Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Results of a Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled. 2009;460-71.

- Lakhan SE, Rowland M. Whole plant cannabis extracts in the treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. BMC neurology [Internet] 2009 [cited 2012 Mar 23];9:59. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi? artid=2793241&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

- Goodman AD, Brown TR, Krupp LB, et al. Sustained-release oral fampridine in multiple sclerosis?: a randomised , double-blind , controlled trial. The Lancet [Internet] 2009;373(9665):732-8. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60442-6

- Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Annals of neurology [Internet] 2011 [cited 2012 Feb 29];69(2):292-302. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3084507&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract