The benefit of 1:1 psychodynamic counselling and couples counselling to people who have suffered from stroke was investigated in this pilot service development project. This work aimed to demonstrate the importance of the provision of stroke psychological services in the community and explore the issues that arose in the course of therapy provided with individuals and couples seen in the course of a year.

Method: seven individuals and four couples were seen. Response to therapy was measured using The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales [1].

Findings: With this small sample of participants, pre-assessment and post-assessment evaluation showed positive changes in the DASS. Assessments revealed high severities of stress, anxiety and depression post-stroke. Important and recurring themes of grief, loss, attachment, dependency, death anxiety and fear are shown.

Discussion: This work adds to the well-known need for increased specialist psychological support for those experiencing moderate-severe mood difficulties following stroke by illustrating the appropriateness of this specific clinical approach. In addition, the value of long-term support groups was shown as a lifeline and focus for a person’s week.

Introduction

Long-term disability is experienced by a third of people living in England who have had a stroke. This disability includes psychological difficulties following a stroke. There are 900,000 people in England who have had a stroke, and 300,000 of these people are living with moderate to severe disabilities. Stroke is the third-largest cause of death [2]. Advances in acute care mean that we are seeing improved survival and reduced morbidity. However, this means that some of the subtler consequences of stroke are now more apparent in the day to day interactions with clinicians. In particular, the cognitive and emotional consequences of stroke are increasingly recognised by clinicians and service users who are seeking help for these problems.

There is a range of long-term difficulties that follow stroke that can impact a person’s mood. It is well recognised that the consequences of a stroke can be experienced as a massive, traumatic event in a person’s life. It can cause feelings of crisis and suicide, and dramatic changes to a person’s physical, emotional and social well-being [3]. Following the shock of a stroke, a person can feel anxious, stressed and depressed. Patients report statements such as “you feel like you want to stay in bed and can’t face things anymore,” “Tasks that were simple take so much effort and concentration,” “It is easy to cry and hard to control,” “You can be snappy and not mean to be,” “You want to avoid people because you don’t want anyone to see you,” “It feels devastating,” “It feels like you’ve lost yourself.”

These are compelling reasons why any therapist would wish to seek to reconsider the services provided alongside existing services. Typically in the UK at present, it is routine for physiotherapy, speech and language therapy, and occupational therapy services to be provided. There has been relatively less attention to the psychological needs of patients in commissioning guidelines despite longstanding recognition of the need to provide such services [4].

Psychodynamic counselling is an approach that enables a person who is struggling to cope with life to have space to explore their feelings and find ways to recover from depression, stress and anxiety. Counselling supports people to move from stages of crisis to develop realistic goals and make adjustments to their self-concepts [5]. This process can be exceptionally challenging and can feel like a fight and a battle to keep going.

Psychodynamic counselling also reflects on past experiences that have relevance to difficult recent life events. For example, a husband is unable to provide for his family triggered feelings about a past relationship that had not been talked about and grieved for.

There are past studies that look at psychotherapeutic interventions for working with stroke. For example, Cunningham’s case study [6] describes the use of personal construct therapy with severe aphasia. Oliveira et al [7] discuss in detail psychodynamic work with physically disabled patients. There is also plenty of literature looking at psychotherapeutic approaches to pain [8]. In addition, Wilson et al’s work on neuropsychological rehabilitation covers various approaches including social and personal identity, systemic family therapy, and narrative therapy [9]. This pilot service has focused on the use of another psychotherapeutic approach called psychodynamic counselling. Many aspects of general psychodynamic theory can be useful when working with those experiencing strokes. In this short introductory review, we will highlight a number of themes including grief, loss, mourning, attachment and fear.

A key theme is grief and mourning. After a stroke, a person can feel lost. Counselling tries to help a person rediscover parts of his or herself that feel lost. Stroke specific psychodynamic counselling helps a person to talk about their sense of loss after their stroke and to encourage a person through their rehabilitation. It also aims to help a person find the resilience to cope with the long-term consequences of a stroke. An added dimension of stroke experienced counselling is the provision of information about expected recovery, the ability to answer some general medical concerns, and to refer on to other professionals such as medicines management.

Understanding unconscious object relations such as the ‘lost object’ is important to psychodynamic counselling. In relation to stroke, the lost object may be a part of the self [10]. Leader proposes ‘Grief is our reaction to loss, but mourning is how we process this grief.’ (p.26). He describes how we anticipate hearing a loved one’s voice on the phone after they have died. This could be compared to someone thinking back to their pre-stroke self and seeing themselves back at work or driving the car. One hypothesis that underpins therapeutic interventions is that the more these memories are processed, feelings begin to improve. Through therapeutic conversations, the sense of discrepancy from ‘pre-stroke’ self may be reduced [9]. For some, this can be a long and difficult process after a stroke. The challenge for counselling following a stroke is to support a person to rediscover parts of themselves and develop an adjusted self-concept. Many people also have losses in their lives where there is mourning still to be done. Counselling helps to look at the unconscious processes of grief and mourning to support people to recover from depression [10].

Following a stroke, a person often feels a lack of confidence and insecurity in their sense of self and especially how they feel about their body. Blando [11] describes the outcomes of Fortner & Neimeyer’s research (1999, p.90) that found higher death anxiety in older people with more psychological problems and a reduced sense of self. Feeling anxious about the prospect of death is known as death anxiety. Awareness of death can be a cause of anxiety, particularly after middle age [11]. Near-death experiences such as suffering a stroke and the memories of the days following a stroke can evoke high anxiety. Death anxiety can restrict how someone engages with life, and this could include restrictions to their recovery and their ability to socialise.

Attachment is also important to any psychotherapeutic approach. The trauma of a stroke can affect attachments, for example, there can be an increased dependency on partners and new strong attachments to health care staff. The stroke may amplify previous attachment patterns such as ‘anxious avoidant’ and ‘anxious resistant’ attachment types (Blando, 2011, p.111-p.112). If someone feels vulnerable, they may feel as insecure as they did as a child. A stroke can cause a person to feel frightened. The support of others helps alleviate these feelings and enables a person to cope better. There may especially be difficulties if a partner has died or a key attachment figure is unavailable. In psychodynamic working, the type of transference and attachment type can be closely associated [11].

In light of these themes, this project was conceived following Speech and Language Therapist Alys Mikolajczyk’s post-qualification training in Psychodynamic Counselling at Cambridge University Continuing Education. Funding from the local Stroke and Heart Network to implement this project was sought and approved because it was recognised that there was a lack of service descriptions and evaluation of work in this field locally, despite the need for psychological support outlined in The National Stroke Strategy for England (2007).

Method

This service was initially advertised to the rehabilitation team to support participants and their families experiencing low moods since a stroke. As a consequence, referrals mainly came from the neurological rehabilitation multidisciplinary teams, though all GP practices in the catchment area were sent a letter and leaflets. People could also self-refer. This service aimed to be flexible by seeing both individuals and couples and aimed to be participant-led and flexible to circumstances. Domiciliary and outpatient sessions were offered.

The number of sessions offered was dependent on the outcome of the initial assessment and the severity of anxiety, stress and depression that was shown. Initially, up to twelve sessions were offered, though as the results will show this changed as the project progressed.

Participants

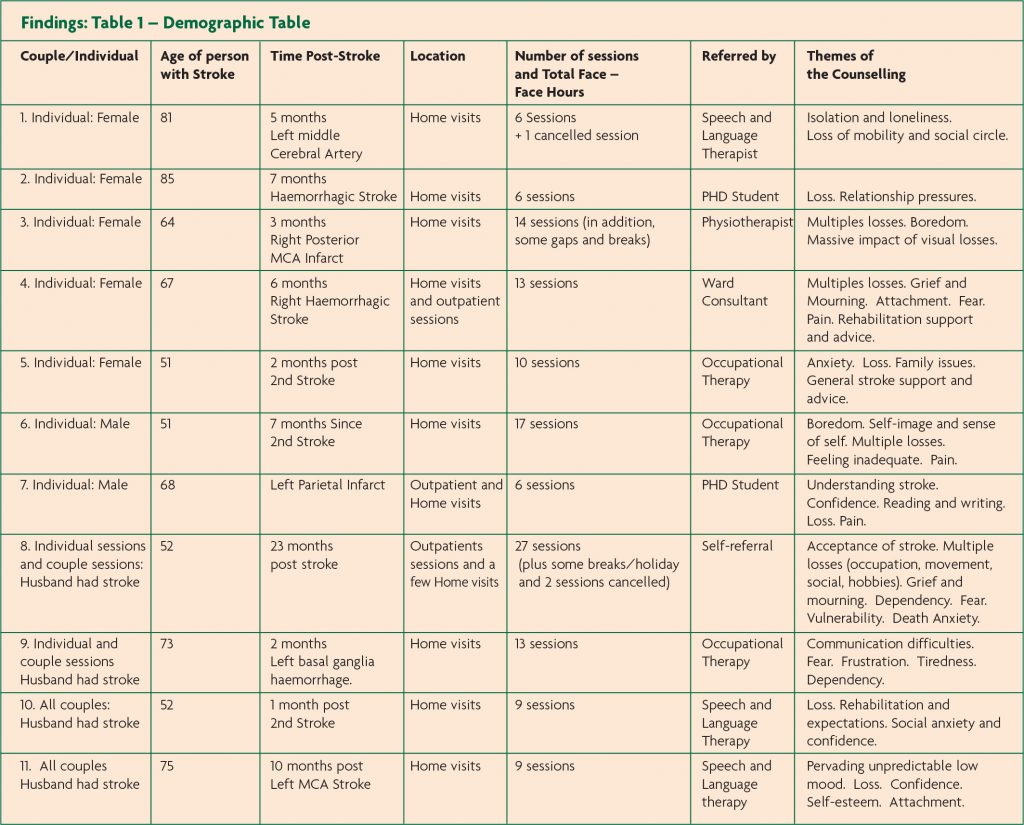

In total, 15 people have been seen over the time period of this project, seven people were seen individually and four couples (see Table 1 for demographics). Due to the high severity of depression, anxiety and stress fewer people were seen than anticipated in the original grant application. At the point of referral [10], participants had experienced a stroke in the last two years, and one man experienced a stroke four years previously. Three participants were referred after a second stroke. All of these three participants reported that they had not received any psychological support after their first strokes and did not know that help existed.

Seven participants were over 65 years and 8 participants were under 65 years. Only one participant had severe speech difficulties, and two other participants had mild-moderate speech and language difficulties.

Outcome measures

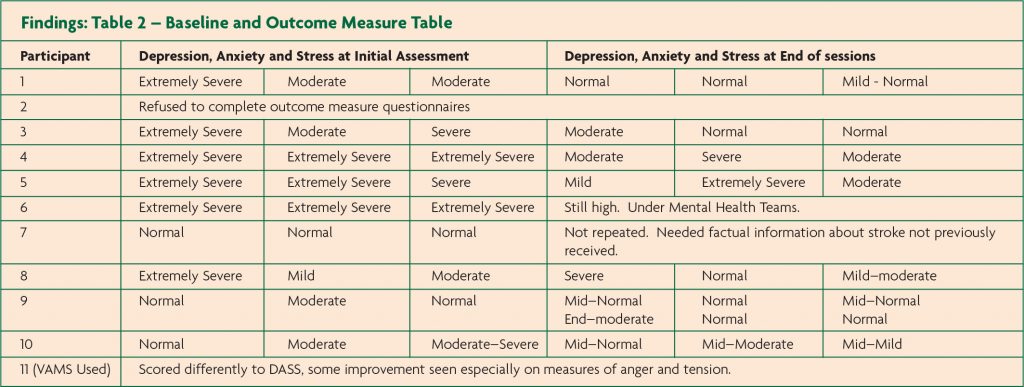

The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales [1] were used with the majority of participants. ‘The Visual Analog Mood Scales’ [12] were used with only one couple. As Table 2 shows, overall outcome measures are very positive and encouraging. Individualised assessment and interview also helped to evaluate outcomes for participants, and for one participant a change questionnaire seemed appropriate.

Results

As this project developed, the level of anxiety and depression in this caseload was found to be moderate to severe. Seven of the people seen were experiencing at least one severe rating on the DASS (The Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales). Four participants needed to be considered for risk issues due to suicidal ideation and one attempted suicide near the start of therapy. With two participants, other services were involved, specifically psychiatry and a community psychiatric nurse in one case and the crisis team and mental health care coordinator in the other. A more detailed cognitive assessment was also completed for two participants by a clinical psychologist specialising in stroke. These complex participants required more time investment and liaisons with other professionals. As a consequence of the overall severity, only three participants were offered the originally-planned six sessions. All other participants were offered more sessions due to need, risk, and multiple life issues. As Table 1 shows, in some cases this was substantially more (range 6-27 sessions), demonstrating the need for long-term treatment for some participants.

One referral was a self-referral from a man and his wife, who were looking for stroke-related counselling due to this man’s severe depression and emotionalism. All other referrals were from the multidisciplinary team and a PhD student. Couples were not always seen together and sometimes only the participant experiencing the stroke was seen. This was flexible to daily circumstances. As Table 1 shows, this service was mainly domiciliary, though three participants were seen both at their homes and as outpatients. Dominant concerns were losses in their lives such as loss of occupation, mobility, income, self-esteem, self-worth and loss of previous overall lifestyle.

It seemed that a psychodynamic approach was appropriate for most of the people seen. With participants 2, 7 & 11 however (See Tables above), the psychodynamic approach was not central. Participant 2 required a supportive client-centred relationship. She required companionship and was introduced to a support group during the duration of our sessions. Participant 7 was one of the later participants in the study and wanted further support to understand his stroke, including the type of stroke he experienced four years previously. He required factual information about his stroke and needed to talk about his difficulties. This participant also required further speech and language therapy guidance for reading and writing, and work on confidence. Participant 11 (a couple) required a mixture of some psychodynamic counselling in the early sessions but also communication advice and support. The couple also benefitted hugely from the long-term support groups they attended (an aphasia support group in their locality). With this couple, their mood deteriorated when a support group was having a break due to staffing problems. In this case, it seemed that long-term conversational support was more valuable than counselling as it provided an opportunity to get out of their home and socialise. For all these three participants (2, 7, 11), the negative mood could be linked to the level of conversational support available to them.

The level of daily activity was a recurring theme for many participants. Reduced ability to participate in daily activities and boredom at home has been a pattern for participants and negatively reinforced low mood. This has shown the crucial need for long-term support groups and health professionals to support the transition back to accessible social and pleasure activities if possible, before discharge from therapy.

Two of the participants experienced severe physical pain during the course of the sessions. It was clear that this influenced their mood and could be associated with suicidal thoughts. Pain management was shown to be crucial for these participants. For client 6, improvements were harder to see on the DASS and were unchanging on objective outcomes. This participant however began to demonstrate positive changes, and though he rated ‘I felt I had nothing to look forward to’ highly (3), he had described looking forward to a trip out and his socialisation was improving. In addition, suicidal comments stopped during the sessions.

Most participants were able to complete the outcome measures, though help was required by one participant to be clear about the meaning of elements of the rating scale. This help was by writing out the choices of 0-3 in a larger font and by giving reminders for each question. With the Visual Analog Mood Scale, the scales were completed together with the couple and differences were discussed as the scales were completed. Sometimes these differences were not anticipated, so this was in itself useful to the counselling work.

Discussion

Importantly, this service development project has identified people experiencing moderate to severe stroke-associated depression, stress and anxiety. Most of these people were already on antidepressants and were in need of psychological support after stroke. It seems to us convincing that there is a need for a service such as this, especially when some risk of suicide has been shown. More specifically for most of these people, support was needed for their feelings of grief, loss, death anxiety and fear.

With the majority of participants, there were multiple issues as well as a stroke. In some cases, a person’s stroke brought out other issues that were repressed and that had not been spoken about before. In other cases, the stroke had coincided with other life issues, such as the loss of parents and businesses, and with the poor health of a family member. Examples of issues for participants covered in this counselling work:

• Recent loss of a mother and similarities in medication and mobility to mother.

• Forced retirement, loss of job, loss of business.

• Loss of mobility and some participants already had losses prior to stroke, such as impaired vision.

• Other medical challenges such as epilepsy, heart attacks, arthritis.

• Difficult family relationships e.g. step-relationships, fostered children.

• Previously undisclosed abuse.

• Losses of siblings at a younger age.

• Previous relationship break-ups and divorce. The trauma of stroke has been central to all the counselling, but exploration of relevant and related issues such as those mentioned above was vital for counselling to be beneficial.

Accessible services that doctors and health professionals know about and know how to refer to are crucial for those experiencing strokes. For three participants that did not have access to psychological support services after their first strokes, we can question whether their assessment outcome measures would have been better at the start of this pilot. A referral pathway for psychological support needs to be clear to all GP services, as some participants’ needs after their first stroke were not recognised and there were limited services to refer to. Some participants said, “I didn’t know services existed; I didn’t get any help after my first stroke.”

We argue that commissioning of Stroke-specialist psychological services is needed for long-term post-stroke. Without this, there will remain poor service provision, such as failing to meet The National Stroke Strategy for England (2007) guidelines [13].

A harder element to articulate in a service development project is the observation that psychodynamic counselling ‘felt’ appropriate to the counsellor for the majority of participants, especially participants, 3, 5, 6, and 8. It was also felt some participants could have continued to benefit from longer-term sessions. One reason was that the dynamic of the sessions seemed appropriate in terms of the application of psychodynamic theory and the rapport, transference, and interpretation of feelings and emotions that evolved.

This service evaluation has shown the value of a stroke experienced counsellor. For example, some of the counselling was aimed at helping the individuals to understand ‘what is normal’ after stroke. The counselling provided included sharing expert knowledge about stroke and giving support and understanding of rehabilitation. Tiredness was a recurring issue with most of the participants seen. In particular, partners understanding issues such as tiredness was important. ‘The Stroke and Aphasia Handbook’ [14] was a much-appreciated resource and reading about these issues was reassuring for some people.

The DASS was shown to be a good accessible outcome measure for these clients as it directed assessment and understanding of the degree of stress, anxiety, and depression. It is interesting to note from the results that the counselling appeared to be more effective at reducing depression than anxiety for participants 4, 5 & 10. With a psychodynamic approach, depression and stress showed greater improvements. It is indicated that further sessions may be needed to reduce anxiety.

At the outset of this project, some group work with participants was anticipated, such as a carers’ group. 1:1 work and couples sessions were however shown to be the most appropriate for this particular group of participants.

This service development project and evaluation has identified that increased psychological support is needed for people following strokes who have moderate-severe depression, stress, and/or anxiety. This small evaluation project demonstrates that increased clinical psychology provision and/or provision of counsellors / psychotherapists specialising in stroke are needed as part of a permanently funded service. This service has shown that 15 participants needed – and benefited from – psychological support that was previously unavailable. This service development project and evaluation was completed one day per week for a year including travel and administration. If services such as this are continued, further people having strokes could benefit. This will have benefits for the health and well-being of those experiencing strokes and their families, and positive benefits to rehabilitation outcomes.

Conclusion

This service development project and evaluation has identified and filled an unmet need for psychological provision after stroke in this locality. All the participants were appreciative of the service and felt that they benefited. The results show that participants’ overall mood improved after receiving this service. The DASS was an appropriate measure to assess mood and enabled changes in stress, anxiety, and depression to be assessed and evaluated.

Psychodynamic counselling was shown to be a potentially effective psychotherapeutic approach and a valuable extension to the community multidisciplinary rehabilitation approach. This evaluation adds further to the literature and evidence base of the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic approaches with stroke. It has also been identified that the commissioning of well-structured psychological support services is needed. Anticipated benefits are likely to include: reduced demand on GPs due to reduced risk, supporting GPs to meet higher ratings on their quality and outcomes framework and therefore making cost savings, and the provision of a high-quality service that meets the quality markers of The National Stroke Strategy (Department of Health, 2007).

Helping to support a person to feel better about life can only be valuable, and therefore this has been a very worthwhile project. One participant’s positive feedback through a change questionnaire made the following comments about the counselling sessions:

“A relief through a difficult time”

“I couldn’t have stayed in hospital if I didn’t have you.”

“Not worried if sitting alone. Not terrified anymore.”

Case Study, illustrating how losses are discussed in therapy

Participant 4 (from Tables 1-2, female, aged 67) was on antidepressants and despite this stress, anxiety and depression were rated as extremely severe initially. There was some risk of self-harm due to low mood and at one point clear suicidal ideation. Losses were multiple, not only severe mobility losses due to her stroke but the loss of occupation and grief for her mother who had recently died.

Sessions were focused on mourning her mother, alongside her own mourning of her previous role. In addition, the counselling was supportive and client-centred and followed her through her rehabilitation when the level of recovery was uncertain.

There was clear reliance on attachment figures with strong dependency in the first year post-stroke. As the sessions progressed, there was less dependency. In our final sessions, she stated, “I’m not worried about sitting alone. Not terrified anymore.”

Outcomes improved from extremely severe to lower levels as shown in Table 2. She was later referred back for a further four sessions due to concern from another health professional that her levels of depression had deteriorated again. She was however maintaining improvement well. Her level of depression had however been extremely severe initially and some level of enduring depression was likely. This is interesting as it shows different perceptions of depression. Participant 4 felt that the counselling was very beneficial to her and described it as, “A relief through a difficult time.” Since these sessions, follow-up appointments have indicated that she has maintained the gains that she made.

References

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. (2004) DASS: The Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales. 2nd ed. School of Psychology, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

- National Audit Office (2005) NHS: Department of Health: Reducing Brain Damage: Faster access to better stroke care.

- Kvigne K, Kirkevold M, Gjengedal E. ‘Fighting back – Struggling to continue life and preserve the self following a stroke.’ In: Health Care for Women International, 2004;25:370-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330490278376

- Royal College of Physicians (2008) National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke. Prepared by the Royal College of Physicians intercollegiate stroke working party. 3rd ed.

- Banks P. Pearson C. ‘Parallel lives: younger stroke survivors and their partners coping with crisis.’ In: Sexual and Relationship Therapy 2004;19(4):413-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990412331298009

- Cunningham R. ‘Counselling someone with severe aphasia: an explo- rative case study’ In: Disability and Rehabilitation 1998;20(9):346-54. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638289809166092

- Oliveira RA, Milliner EK, Page R. ‘Psychotherapy with Physically Disabled Patients.’ In: American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2004;58(4):430-41. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2004.58.4.430

- Hsu MC, Schubiner H. ‘Recovery from Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain with Psychodynamic Consultation and Brief Intervention: A Report of Three Illustrative Cases.’ In: Pain Medicine. 2010;11:977-80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00853.x

- Wilson BA, Gracey F, Evans JJ, Bateman A. (2009) Neuropsychological Rehabilitation: Theory, Models, Therapy and Outcome. Cambridge University Press, UK. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511581083

- Leader D. (2009) The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia and Depression. London, England, Penguin Books.

- Blando, John (2011) Counseling Older Adults, East Sussex, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Stern R. (1997) Visual Analog Mood Scale -VAMS. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. USA.

- National Stroke Strategy for England (2007) NHS: Department of Health

- Parr S. (2004) The Stroke and Aphasia Handbook. London. Connect.