Introduction

The concept of patient and public involvement (PPI) in healthcare has been around since 1974, however it has been a struggle for it to be effectively implemented and supported,1 as evident by several organisations set up and abolished over time (table 1 below).2 Specific to health research, PPI has recently become a popular notion and as such is the standard expectation by most government funded health research. The need to increasingly hold researchers to account, recognise barriers in knowledge and research, and occasionally, the unrealistic expectations, have dominated research regulations.3,4 Therefore, there has been a growing requirement to give patients and the public the ability to contribute and shape research.5,6 This increase in PPI allows for greater quality reassurance and provides the certainty that the research being conducted will be beneficial for making the concept of bench-to-bedside a reality.7,8

Table 1: Brief summary of PPI set up in NHS (England)

| 1974 | Community Health Councils (CHCs) set up |

| 2000 | Overview and Scrutiny Committee set up |

| 2002 | CHCs abolished |

| 2003 | Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health (CPPIH) |

| 2003 | Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS), Independent Complaints Advocacy Service (ICAS), and Patient and Public Involvement Forums (PPIfs) set up |

| 2004 | CPPIH abolished |

| 2006 | PPIfs abolished |

| 2006 | Local Involvement Networks (LINks) set up |

| 2013 | LINks abolished |

| 2013 | Healthwatch England set up |

The Health Research Authority (HRA) in the UK conducted a survey on public attitude towards medical research in which they found patient’s would have greater confidence in research if they had counselled the design and implementation of the research study.9 Many patients are well equipped with understanding their own condition through experience, sometimes, better than the clinicians and researchers. Therefore, their ambitions and viewpoints may not have been considered by those conceptualizing research for their condition. By having PPI in active partnership with the researchers and clinicians, a unified research design is achieved which is likely to have beneficial effects to patients and the National Health Service (NHS). This is echoed by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) who are often concerned by the patient specific aspects such as consent, recruitment and information quality, much of which can be addressed by a PPI group.10 A few core fundamental aspects of having a PPI in research are that it will help:11,12

- Corroborate the relevance of the project to the patients;

- Improve the basic research question;

- Identify appropriate research methodologies;

- Understand the potential outcomes for patients;

- Achieve greater understanding of how to enable the research to deliver to time and target (i.e. recruiting patients in research period).

NIHR Initiatives

The National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) work to provide support and guidance to researchers in various ways to deliver practical research, which work to make patients and the NHS better.13 One of the aims of NIHR is to empower patients and the public to participate and shape research,14 hence, they fund an advisory group, INVOLVE. This group is one-of-a-kind in the world, and works to collate expertise and experiences in research through increasing public involvement.15 INVOLVE are defined as a group aiming for research to be carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ the public rather than research ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ the public.16 The NIHR has set out various PPI guidelines with the aim to ensure researchers involve the public in their studies as much as possible, hence safeguarding the practicality of the research outcome. As a result, INVOLVE sets out detailed guidelines for researchers to follow ensuring the successful achievement of PPI.16

…attending these meetings allows me to hear a patients prospective and experience of my clinics which is very helpful as I can then go back and make appropriate changes to further help my patients…Miriam Parry (Specialist PD nurse, CRISP)

The importance of PPI in research is evident in all stages of submitting project proposals and up to the final report. This is echoed by the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Center (NETSCC), which manage the NIHR, Evaluation, Trials and Studies (NETS) programs, who expect there to be active PPI in any research they fund and support.17

What is the impact of PPI?

A review into the impact of PPI has been undertaken by Staley (2009) who reported to find there being a significant effect on the identification of the research question to the designing and delivering of the project.18 Staley also finds early involvement to be beneficial for cost and ethical difficulties which may later arise. Their review highlights that the impact of PPI has no robust method of evaluation. Nonetheless, the general opinion is that PPI has a positive impact on research in almost all aspects. Brett and colleagues (2014) conducted a review of the impact PPI have on research whereby they found PPI helped identify researcher’s limitation in knowledge, which equipped them to then develop to resolve these problems. Alongside these practical benefits of having PPI, they have also been shown to have financial benefits by helping to prevent potential losses through helping refine and identifying pitfalls in projects during the design stage.6,19,20 Several studies have shown successful design and implementation of research, following PPI group advice, which provided vital information to conduct successful research.21-27 INVOLVE, along with the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN) and the School for Primary Care Research, commissioned case studies looking at research and PPI,28-32 and found a significant positive impact of PPI.

Whilst PPI is certainly not a new model, as evident by mental health research utilizing PPI involvement for decades now, it is not as well-established in all specialties. Neurodegenerative conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), are set to rise 28% by 202033 creating a substantial need to perpetuate research in this field. Hence, the need for robust PD PPI has been an unmet need for some time, however, this is now changing.

Local Initiative at King’s translating to a national project

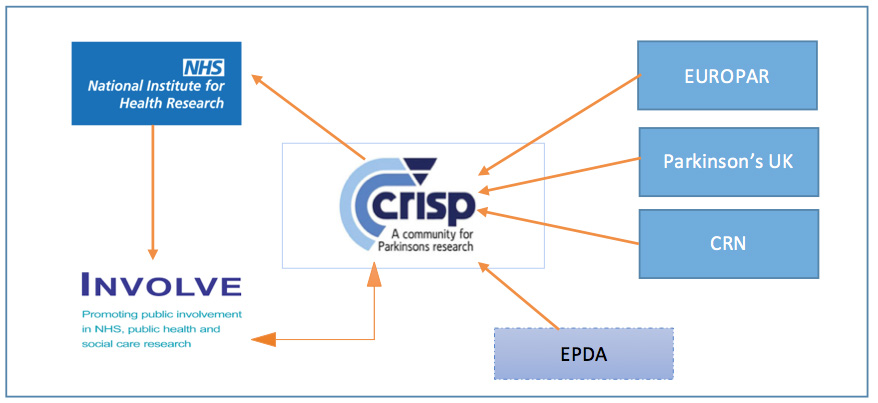

King’s College Hospital (King’s) Parkinson’s center led the development of the ‘King’s PPI group’, which consisted of a range of public representatives (patients, carers) and NHS trust staff (researchers, health professionals) as well as representation from key PD patient charities (see picture 1). The original members of King’s PPI, where approached following a movement disorder multidisciplinary team meeting at the trust. Potential patients where asked if they would like to be involved, subsequently, on accepting, they were sent a formal letter of invitation. Since this initial recruitment, leaflets and informative posters have been created and placed in clinics to help encourage patients and the public to participate in research.

This group later renamed itself as CRISP (Community for Research Involvement and Support for people with Parkinson’s). Furthermore, the logo for CRISP itself was designed by one of the Patients with Parkinson’s (PwP) representatives. CRISP was created to incorporate the requirements and guidance from the NIHR regarding conducting successful and meaningful research for PD patients and carers. It therefore runs in line with INVOLVE guidelines and is supported by several other research organizations including EUROPAR (European network for Parkinson’s), Parkinson’s UK and London South CRN (Clinical Research Network).34 The concept behind this group is underpinned by the fact that they work to contribute towards the design and development of research projects in accordance with patient and caregiver opinions and needs.34

What are the aims of CRISP?

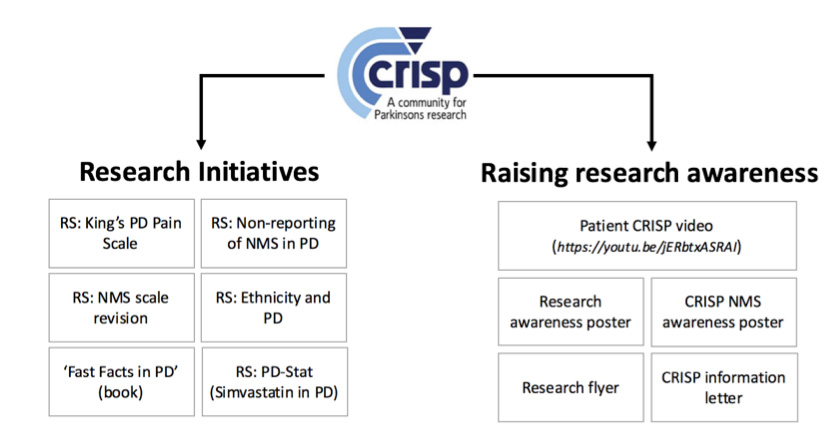

CRISP is based at King’s College Hospital in South London and predominately deals with Parkinson’s based research. They meet with representatives from each group working to discuss (a) the design, development and practicality of research projects, (b) discussing and reviewing current research, (c) gathering patient and public opinions on proposed projects and (d) generating novel concepts for research the group feels needs to be undertaken.34 The primary aims of CRISP can be summarized into two categories; research initiatives and raising research awareness. See figure 2 for a diagrammatic representation of CRISP aims, with a few examples.

CRISP & Research

The members of CRISP typically meet on a quarterly basis with each meeting lasting around 2 hours. During a meeting, researchers provide a printed list of all ongoing and proposed projects at the Trust sites. Each project synopsis is provided and discussed with the CRISP members, enabling an atmosphere whereby both researchers and members can ask questions. This form of discussion has proven to be very useful in the past. For example, one project requiring patients to attend clinic in ‘off’ state would need to consider how difficult it would be for a patient to arrive to the clinic in that state, hence suggestions of staying overnight at the hospital or local hotel would be more practical and achievable. With some urgent progress on new and upcoming projects arising throughout the year, the members are all reachable via email or post if their involvement is particularly useful and required prior to an upcoming meeting.

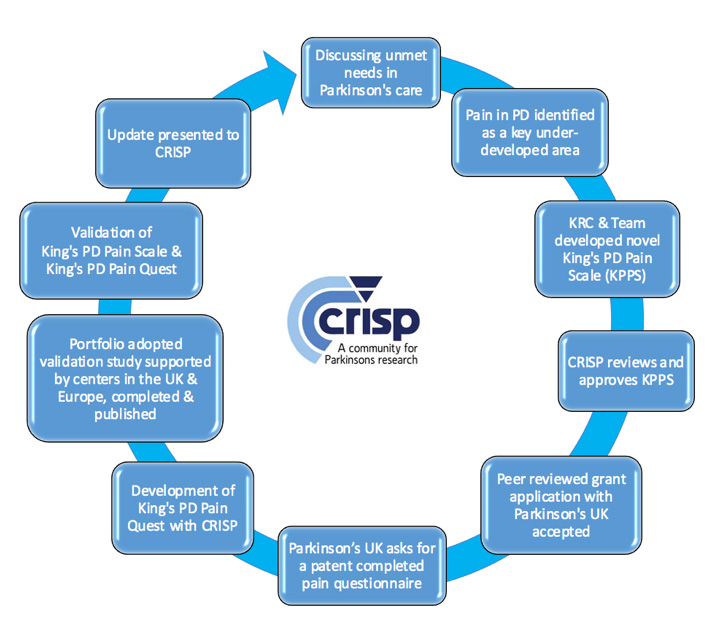

Research groups in Parkinson’s, such as EUROPAR, have utilized CRISP by involving the members to participate and review new editions of patient-friendly books (i.e. the ‘Fast Facts in PD: 4th edition’) and helped the fine-tuning of inclusion criteria for some research projects (i.e. PD simvastatin clinical trial) prior to submission for approval. 35 This type of collaborative work has led to many successful identification and changes in the NHS and work worldwide, with regards to the way we approach Parkinson’s patient care. One success story of a CRISP-led project has been the development of the King’s Parkinson’s disease Pain Scale (King’s PD Pain Scale), which is now a validated scale.36 See figure 3 for the outline of how CRISP was involved in the making of this scale.

CRISP & Patient awareness video

It is essential to appreciate the difference between the involvement and participation, whereby patient involvement is achieved through PwP represented in CRISP, whilst patient participation is the active partaking in clinical research. CRISP works to promote both aspects through various means (i.e. leaflets, videos).

… there are academics who devote their whole career to understanding a small part of the puzzle, […] e.g. Parkinson’s. If I can be part of that processes, then my future with [PD] looks more positive and the future of my three children without PD looks more certain… Suzanne Pitts (PwP, CRISP)

For research to be beneficial in the real world for patients, it must be trialed and tested to ensure it works. However, due to lack of public awareness and misunderstanding as to what might be expected from the patient, this leads many researchers to have patient recruitment problems.37 This has been addressed by CRISP through the development of a video whereby CRISP members speak about their experience with active and advisory PPI. This video has now become a regular feature on the NIHR TV (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jERbtxASRAI), as well as being displayed in the clinical waiting rooms for patients. Along with the video, there has been a range of positive material such as flyers and letters by CRISP to raise awareness for research in the public.

… CRISP is a good representation of everyone involved in PD… it has helped us understand how research works and the steps involved. It allows for more appreciation of the work done and what needs to be done… Eros Bresolin (PwP, CRISP)

By creating these promotional materials, CRISP has worked to help achieve goals set by research organizations. The NIHR and INVOLVE, both work to promote a multi-disciplinary approach to research whereby clinicians, researchers and senior academics should have PPI implemented in every step of the project. CRISP, since 2011, has established an essential role in fulfilling NIHR, and further the HRA, expectations of an Excellent Research Centre. This has been achieved through the identification of problems that Parkinson’s patients experience and allow research to be tailored to ensure the actual problems are being addressed.

…modern treatments for Parkinson’s only became available after research and testing on [PD] patients. Seems only fair, therefore, that I make my own contribution… you never know, research may lead to treatment beneficial to me…David Charlton (PwP, CRISP)

Future of PPI

Depending on the funder, PPI is becoming a mandatory condition on many applications for researchers. Furthermore, dedicated toolkits and frameworks are now set-up (i.e. Public Involvement Impact Assessment Framework (PiiAF) to aid in assessing PPI impact on projects. However, some funding bodies still do not set PPI as a mandatory requirement, moreover funding for PPI is currently limited. Movement disorder specific PPI are still sparse, and following the success and achievements of CRISP, it is necessary to establish specific PPI in each research center in the UK. This will address the need to improve patient and public knowledge about research participation and involvement.

References

- Hogg CNL. Patient and public involvement: What next for the NHS? Health Expectations. 2007;10(2):129-138.

- Committee, H.o.C.H. Patient and Public Involvement in the NHS, 3rd report. H.o. Commons, Editor. 2007.

- Kelman CW, Bass AJ, Holman CDJ. Research use of linked health data — a best practice protocol. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2002; 26(3):251-255.

- Boaz A, Biri D, McKevitt C. Rethinking the relationship between science and society: Has there been a shift in attitudes to Patient and Public Involvement and Public Engagement in Science in the United Kingdom? Health Expectations. 2016; 19(3):592-601.

- Bastian, H. The Power of Sharing Knowledge. Consumer participation in the Cochrane Collaboration. UK Cochrane Centre, 1994.

- Boote J, Telford R, Cooper C. Consumer involvement in health research: a review and research agenda. Health Policy. 2002;61(2):213-236.

- Entwistle VA, et al. Lay perspectives: advantages for health research. BMJ, 1998;316(7129):463-466.

- Chalmers I. What do I want from health research and researchers when I am a patient? BMJ. 1995;310(6990):1315-1318.

- HRA N. Patient involvement increases public confidence in health research. News 2013 [cited 2016; Available from: http://www.hra.nhs.uk/news/2013/11/22/patient-involvement-increases-public-confidence-health-research/.

- INVOLVE. Impact of public involvement on the ethical aspects of research. H.R. Authority, Editor. 2016.

- INVOLVE, Patient and public involvement in research and research ethics committee review INVOLVE, 2009.

- INVOLVE, Public involvement in research and research ethics committee review, H.R. Authority, Editor. 2016. p. 4.

- NIHR. Five year strategic plan for research delivery: 2012-2017. NIHR Clinical Research Network 2012; Available from: https://www.crn.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/About%20the%20CRN/CRN%20Strategic%20Plan%202012-17.pdf.

- NIHR. Vision/ Mission/ Aims. 2015; Available from: http://www.nihr.ac.uk/about/mission-of-the-nihr.htm.

- INVOLVE. About INVOLVE. 2015 [cited 2016; Available from: http://www.invo.org.uk/about-involve/.

- INVOLVE, Briefing notes for researchers: public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. 2012.

- NIHR. Public Involvement in your research. 2016; Available from: http://www.nihr.ac.uk/funding/public-involvement-in-your-research.htm.

- Staley K. Exploring Impact: Public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research (INVOLVE). NIHR. 2009:116.

- Brett J, et al. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Patient and Public Involvement on Service Users, Researchers and Communities. The Patient – Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2014.;7(4):387-395.

- Shippee ND, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expectations. 2015;18(5):1151-1166.

- Holm KE, et al. Patient Involvement in the Design of a Patient-Centered Clinical Trial to Promote Adherence to Supplemental Oxygen Therapy in COPD. The Patient – Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2016; 9(3):271-279.

- de Wit M. Patient Participation in Rheymatology Research: a four level response evaluation. 2013, University of Bristol.

- Howe A, et al. Public involvement in health research: a case study of one NHS project over 5 years. Health Care Research & Development. 2010;11(1):17-28.

- Pohontsch NJ, et al. The professional perspective on patient involvement in the development of quality indicators: a qualitative analysis using the example of chronic heart failure in the German health care setting. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:151-9.

- Bray, L, Collier S. Research essentials: Developing and designing research through consultation and collaboration with children and young people. Nursing Children and Young People. 2016;28(4):12.

- Kreindler, SA, Struthers A. Assessing the organizational impact of patient involvement: a first STEPP. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2016;29(4):441-53.

- Hyde C, et al. Process and impact of patient involvement in a systematic review of shared decision making in primary care consultations. Health Expect, 2016.

- Pinfold V, et al. Putting lay voices into primary care research : PPI strategies and early steps in the PARTNERS2 study, in School for Primary Care Research conference. 2014, NIHR.

- Robens S. Improving Physical Health and Reducing Substance Use in Severe Mental Illness (IMPaCT) A case study on carer involvement in mental health research. 2013, NIHR.

- Robinson L. Supporting Excellence in End of life care in Dementia – SEED programme. INVOLVE NIHR, 2013.

- Staley K. The Super EDEN Programme – A case study illustrating the impact of service user and carer involvement. NIHR, 2013.

- Staley K. The PRIMROSE programme – A case study illustrating the impact of service user and carer involvement. 2013, NIHR.

- UK, P.s. Number of people with Parkinson’s in the UK is set to rise. 2012; Available from: http://www.parkinsons.org.uk/news/23-january-2012/number-people-parkinsons-uk-set-rise.

- CRISP, CRISP: Terms of reference. 2015, parkinsons-london.co.uk.

- CRISP, CRISP – EUROPAR Patient Group Meeting, T. Chiwera, Editor. 2015.

- Chaudhuri KR, et al. King’s Parkinson’s disease pain scale, the first scale for pain in PD: An international validation. Mov Disord. 2015;30(12):1623-31.

- Chew-Graham, C. Positive reporting? Is there a bias is reporting of patient and public involvement and engagement? Health Expectations. 2016;19(3):499-500.