Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly had a sizeable impact on the health and day and night time behaviours of populations around the world. In the UK, lockdown and social distancing measures vastly reduced mobility as citizens worked from home and the clinically vulnerable begun shielding indoors. Compared to pandemics of old, large datasets now exist which give fascinating insight into pandemic-related behavioural change. This paper investigates how publicly available data from technology companies can be examined to build up a picture of how sleep and circadian rhythm changes in locked down populations.

Introduction

The social distancing measures introduced by governments around the world in response to the covid-19 pandemic has brought about sudden and massive change to the lives of entire populations.1 The lockdown has inevitably had an effect on the behaviours and quality of life of the general public, from employment rates to mental health.2 A symptom of this change was seen in late March when media giants Netflix and YouTube reduced the quality of their streaming services to cope with increased demand.3,4 In response to the coronavirus pandemic, Netflix experienced 15 million new subscribers, and Spotify 6 million new Premium users.5

Few physiological processes are as influenced by our behaviour as sleep. Given the sudden and extreme rift in the behaviour of society, it is reasonable to assume that the lockdown has had some impact on how the population is now sleeping. This paper examines ways in which big data can be used to understand shifts in behaviour and sleeping patterns.

The role of structure in entraining the circadian rhythm

The circadian rhythm, in the absence of zeitgebers (light, food, temperature) usually spans longer than 24 hours. When light is received by the retina, a signal travels to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) causing the pineal gland to stop releasing melatonin, encouraging the sleeper to wake and entraining the rhythm to 24-hours.6 This negative feedback loop is also triggered by artificial light from phones and TV screens.7 The social zeitgeber theory proposes that social changes also act as zeitgebers, with disruption negatively affecting circadian synchronicity, disrupting biological processes and predisposing individuals to insomnia and depression.8 Combined with the effect of artificial light on sleep times, circadian disruption is therefore likely in a pandemic.9

What the Big Data Giants tell us about behavioural change

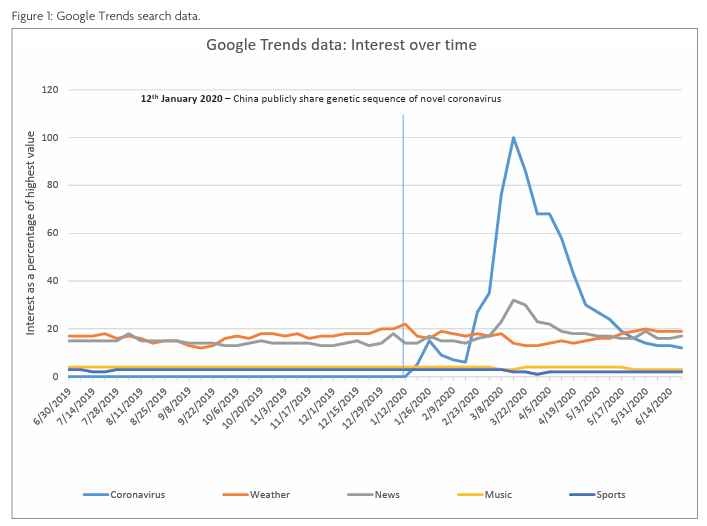

Google Trends (figure 1) shows a sharp increase in ‘coronavirus’ searches over the course of the pandemic.

Spotify

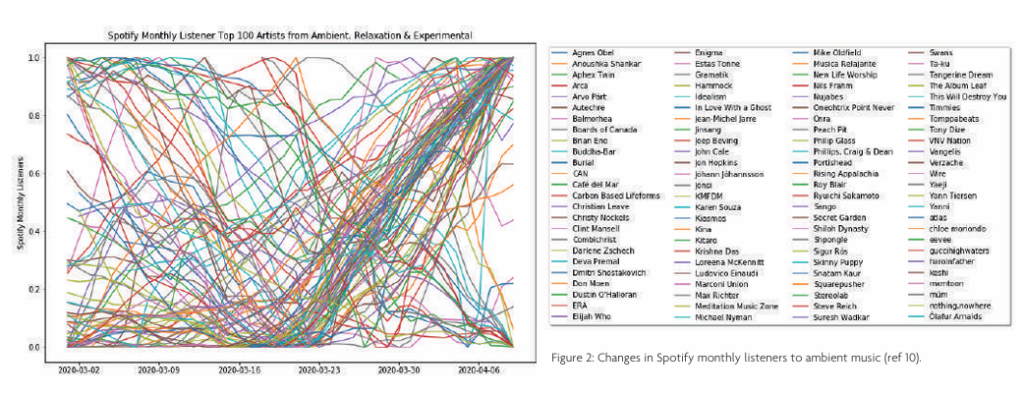

The music streaming giant commented “morning routines have changed significantly. Every day now looks like a weekend.” Streaming via mobile devices decreased, whilst streaming via static devices increased by over 50%, indicating more from home listening. ‘Chill’ and ‘ambient’ genres were sought after whilst rap and rock music were less so (figure 2).10 This may indicate listeners were streaming music for calming effect, including managing anxiety and insomnia.

Sleep Analytics

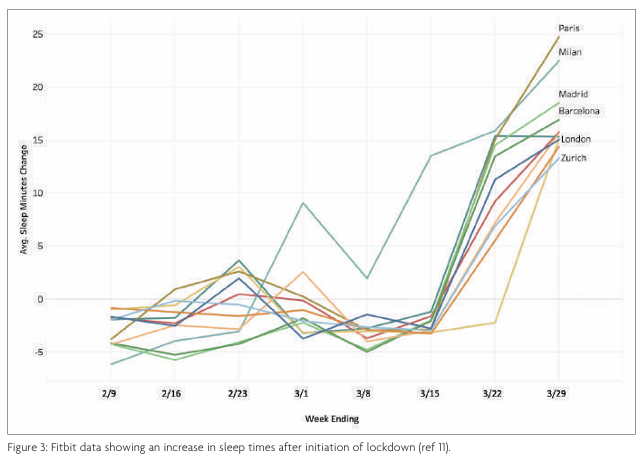

European data from Fitbit (figure 3) showed an increase in the average number of minutes slept per night since the lockdown took place in each city.11

Internet traffic

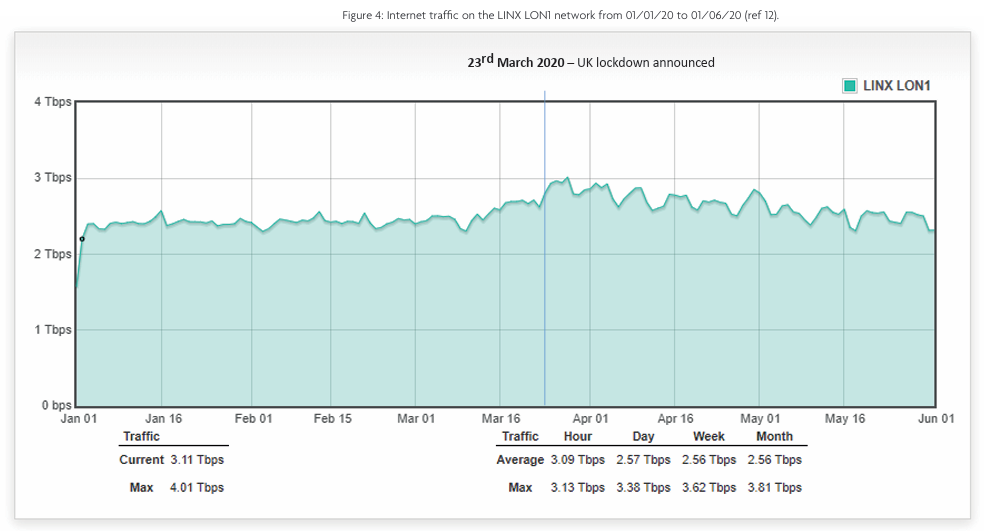

The London INternet eXchange (LINX) is a network of internet routers in London.12 Although this data is not representative of total UK internet usage, it is likely to shadow national usage.

A significant change was seen in the LINX LON1 internet traffic throughout 2020. In the 10 days preceding the lockdown, a rise in the baseline of internet traffic can be seen. The structure of internet traffic over time changes too, with clear troughs in total daily traffic at weekends, and daily consumption higher on weekdays (figure 4). This may indicate those in lockdown working from home and turning to streaming services for entertainment.

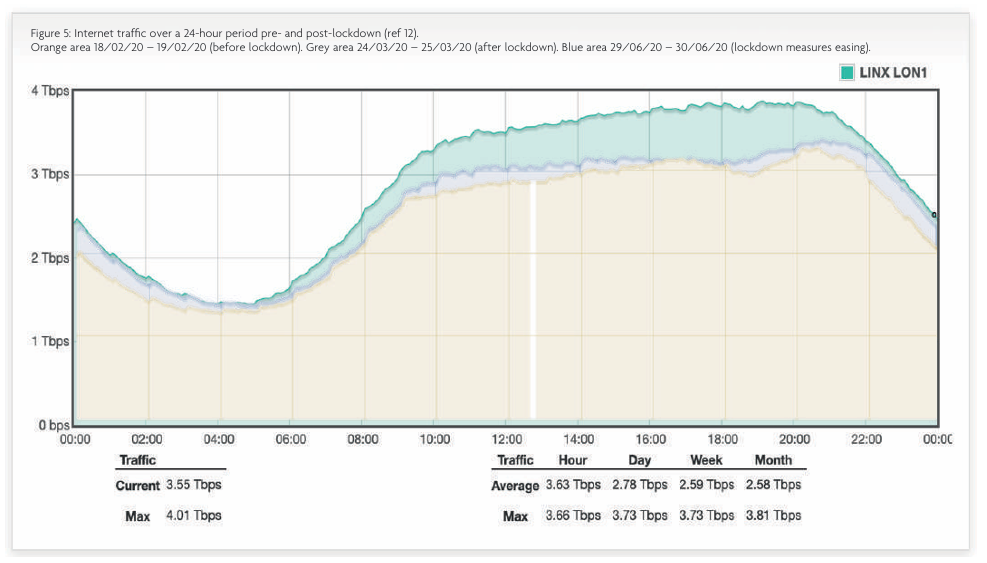

The network traffic has a circadian-like cycle, peaking in the day and dropping to nadir overnight (figure 5). Comparing an average 24-hour period before lockdown versus one immediately after (controlling for weekday), greater traffic can be seen at every hour of the 24hour period following lockdown. Three months later as lockdown measures ease, internet traffic throughout the day resembles more the pre-lockdown figures, whilst late night and small-hours traffic remains almost exactly the same.

Orange area 18/02/20 – 19/02/20 (before lockdown)

Grey area 24/03/20 – 25/03/20 (after lockdown)

Blue area 29/06/20 – 30/06/20 (lockdown measures easing)

At around midnight each night, traffic falls below 2Tbps until around 7:30am the following day. Using this as an estimate for the sleep and wake times of the population, changes to internet traffic may indicate changes to circadian rhythms.

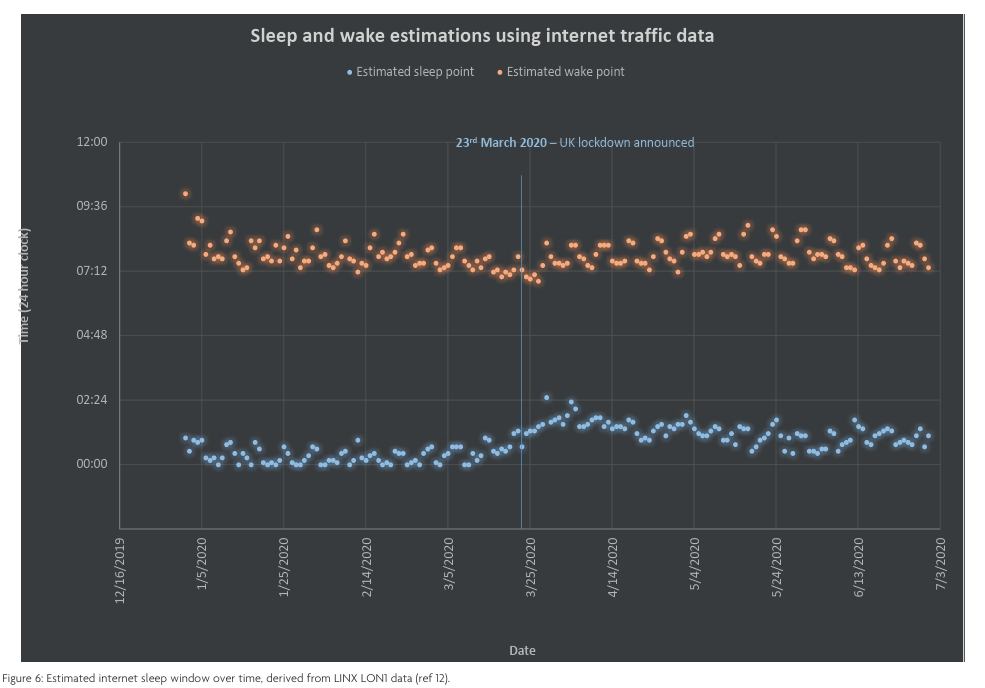

The data was extracted from each 24-hour period of LINX LON1 network data at points where the internet traffic falls below 2Tbps (estimated population sleep point) and rises above 2Tbps (estimated population wake point) for the time period 01/01/20 – 30/06/20 (Figure 6).

A clear change can be seen around the time of the lockdown. Greater traffic post-lockdown indicates increased use of technology until later into the night, and likely a later bedtime by an extra 1-2 hours.

A small delay (~30 minutes) was seen in the increase in morning traffic post-lockdown, indicating that people are sleeping in for longer. Overall total sleep time has reduced. This contrasts with Fitbit data presented earlier in this article. Those using Fitbit may be more sleep aware and capitalise on extra sleep opportunities in lockdown.

Post-lockdown a clearer distinction is evident between weekdays and weeknights: every five weekdays is followed by two later weekend points. This would suggest that the population are treating their evenings more like weekends and staying up later, yet waking at a similar time to pre-lockdown (possibly due to working from home), and experiencing greater social jetlag at weekends because of this self-inflicted sleep compression.

Conclusion

This paper highlights the potential to derive inferences about population level circadian rhythm from big data. Internet traffic data is identified as an indicator for population level sleep disturbances. Lockdown has caused a transient shift in sleeping patterns, delaying the circadian phase of the population through loss of circadian entrainment as daily routines have dissolved. Whilst staying at home and saving lives, the UK population went to bed later, woke slightly later on weekdays and later still on weekends suggesting that paradoxically, social distancing increased social jetlag. Perhaps rather than a month of Sundays, lockdown has created a month of Saturday nights followed by Monday mornings.

References

- Elmer T, Mepham K, Stadtfeld C. Students under lockdown: Assessing change in students’ social networks and mental health during the COVID-19 crisis 2020. doi:10.31234/osf.io/ua6tq.

- Cellini N, Canale N, Mioni G, Costa S. Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J Sleep Res. e13074. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13074

- Gold H. Netflix, YouTube slow down streaming in Europe [Internet]. CTVNews. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.ctvnews.ca/entertainment/netflix-youtube-slow-down-streaming-in-europe-1.4861059

- Netflix to slow Europe transmissions to avoid broadband overload [Internet]. the Guardian. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 30]. Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/media/2020/mar/19/netflix-to-slow-europe-transmissions-to-avoid-broadband-overload

- Spotify Technology S.A. Announces Financial Results for First Quarter 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 30]. Available from: https://investors.spotify.com/financials/press-release-details/2020/Spotify-Technology-SA-Announces-Financial-Results-for-First-Quarter-2020/default.aspx

- Arendt J, Broadway J. Light and Melatonin as Zeitgebers in Man. Chronobiol Int. 1987 Jan 1;4(2):273–82.

- Stevens RG, Zhu Y. Electric light, particularly at night, disrupts human circadian rhythmicity: is that a problem? Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2015 May 5;370(1667).

- Ehlers CL, Frank E, Kupfer DJ. Social Zeitgebers and Biological Rhythms: A Unified Approach to Understanding the Etiology of Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988 Oct 1;45(10):948–52.

- Erren TC, Lewis P. SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 and physical distancing: risk for circadian rhythm dysregulation, advice to alleviate it, and natural experiment research opportunities. Chronobiol Int. 2020 Jun 5;0(0):1–4.

- Joven J, Rosenborg RA, Seekhao N, Yuen M. COVID-19’s Effect on the Global Music Business, Part 1: Genre [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 30]. Available from: https://blog.chartmetric.com/covid-19-effect-on-the-global-music-business-part-1-genre/

- The Impact Of COVID-19 On Global Sleep Patterns [Internet]. Fitbit Blog. 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 30]. Available from: https://blog.fitbit.com/covid-19-sleep-patterns/

- LANs Flow | LINX Portal [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 30]. Available from: https://portal.linx.net/lans_flows