Abstract

Lies are like sleeping pills. You should only use them when you absolutely have to. They spoil everything if you make a habit of them.

Daniel Quinn

Introduction

Scarcely a day goes by without sleep being in the news. One long-running strand concerns media coverage of sleep medicines, particularly the Z-drugs (i.e. Zopiclone and Zolpidem), which have tended over time to receive a bad press. Rising prescription numbers, escalating costs to the NHS, and raised mortality risks all hint at an epidemic of “misprescribing”, creating new anxieties for our patients with insomnia to keep them awake at night.

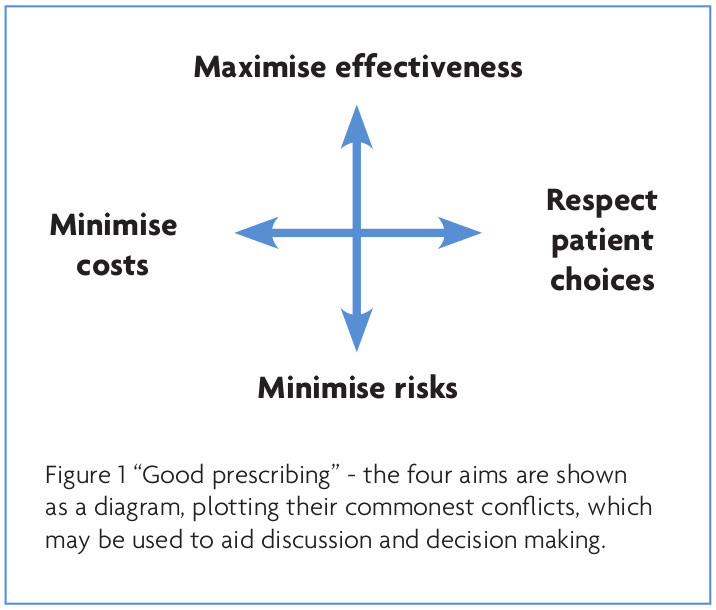

Conversely though, there is a paucity of information available on what constitutes “good” Z-drug prescribing. What is more, various guidelines tend to imply that the right answer exists, rather than recognising the complex trade-offs that often have to be made. One model of good prescribing brings together the traditional balance of benefits and risks, with the need to reduce costs, and the right of patients to make treatment choices1 (see Figure 1). Using this model, I explore how to avoid misprescribing Z-drugs.

Maximising effectiveness

Z-drugs are licensed for the treatment of insomnia, and so the first step in maximising effectiveness is to ensure that one’s sleep diagnosis is correct!

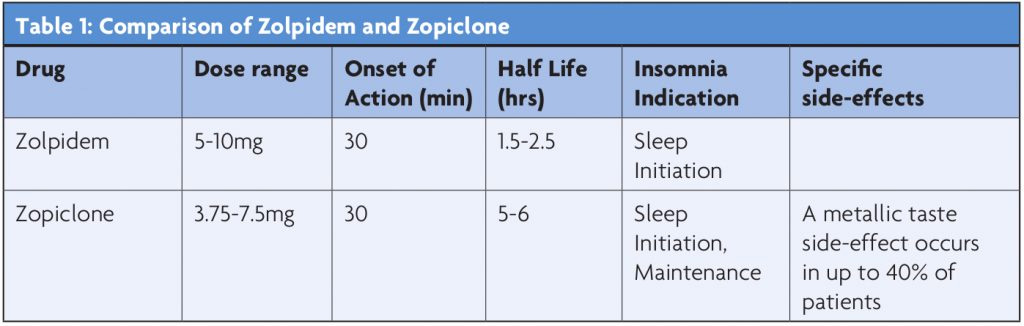

Choosing between Zopiclone and Zolpidem will then largely be dependent on which period of the night one wants to cover (see Table 1).

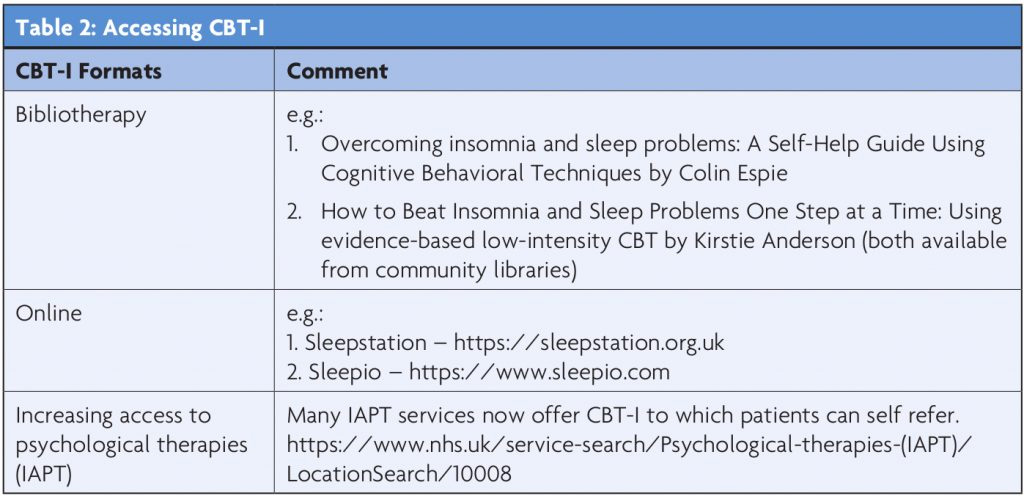

Hypnotics are not general anaesthetics, and work best when the sleep-wake cycle is optimised. The best way to achieve this is via Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I). Therefore, whenever one reaches for the prescription pad, CBT-I should also be discussed and commenced. CBT-I includes a combination of behavioural and cognitive techniques in order to change maladaptive sleep habits, to lower sleep-disrupting arousal (cognitive or physiological) and to alter sleep-related misconceptions and thought patterns. Whilst it seems logical to advise good sleep hygiene for patients with insomnia, there is no evidence that this is a successful intervention on its own.2 Access to CBT-I has been cited as a difficulty,3 but there are a variety of evidenced bibliotherapy and online resources which help to circumnavigate this4,5 (Table 2).

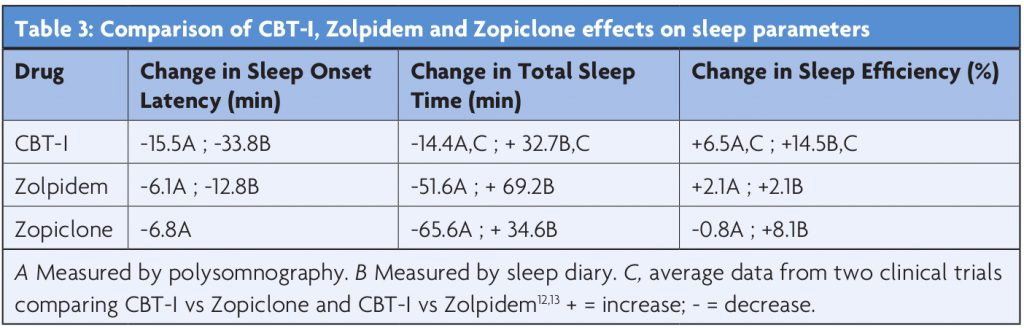

CBT-I shows longer-term benefits than pharmacotherapy,6 has few physical side-effects (fatigue can be troublesome in the initial stages of therapy), and is preferred by patients.7 The American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s task-force report concluded that CBT-I in uncomplicated cases is associated with an improvement in 70% of patients, and is maintained for at least six months post-treatment.8 Table 3 compares the efficacy of CBT-I to the Z-drugs in changing sleep parameters. Combination therapy using Zolpidem with CBT-I was better than either treatment alone in one randomised controlled trial.9 Z-drugs are licensed for short-term use in the UK (i.e. up to four weeks), and are probably ideally used as a stepping-stone until a patient can access or has completed CBT-I. Up to 85% of patients are able to successfully stop their hypnotics following CBT-I, as opposed to 14-28% who are advised by their clinician to do so.10,11

Minimising risks

Various adverse events resulting from, or associated with Z-drug use have been extensively reported. Among these, motor vehicle accidents, falls in older adults, and the risk of dementia have attracted the most attention.

A pooled analysis of four studies on Zopiclone’s potential for residual sedation contributing to driving risk demonstrated that impairment lasted up to 11 hours post-dosing, and was not dependent on age or sex.14 Studies on Zolpidem in healthy adults, did not demonstrate any driving impairment with early or middle of the night dosing e.g. (ref 15). However, for adults aged 55-65, deviations in alertness and speed have been reported.16 The International Council on Alcohol, Drugs and Traffic Safety (ICADTS) has ranked various medications based on their potential for causing impaired driving (I = presumed safe, II = minor to moderate impairment, III = severe impairment), with Zopiclone ranked at III and Zolpidem ranked at II.17 Younger drivers, those new to the Z-drugs, sleep deprivation and combination with alcohol and other sedative medications all increase the risk. It is therefore important to warn patients of this potential risk when commencing Z-drugs.

The literature on Z-drug associated falls in older adults has yet to reach a consensus. For every study that demonstrates an association, there is another which refutes it e.g. (ref 18). Moreover, insomnia on its own confers a risk of falls in this age group.19 The risk is certainly increased, when older adults are prescribed a Z-drug which is ineffective for them. Being awake and mobile in the night with a Z-drug on board will increase the risk of falls. Therefore, if the Z-drug is ineffective, it should be stopped. Higher Z-drug doses, psychotropic poly-pharmacy and poor mobility all increase the risk of falls and subsequent bone fractures.

Dementia of any type remains one of the most feared disease states, and any association with Z-drugs is a common worry for patients with insomnia. For many patients, Z-drugs certainly cause acute and reversible cognitive dysfunction (e.g. amnesia, slurred speech etc). However, whether or not they cause progressive neurodengerative disease has yet to be elucidated. The evidence relating to Z-drugs being associated with dementia is scant, and is mostly dependent on a few sub-analyses of wider benzodiazepine studies e.g. (ref 20). One single Taiwanese case–control study reported an increased risk of dementia with Zolpidem compared with for non-users.21 However, sleep disturbance is a common early symptom of dementia, and whether these patients were already on a dementing trajectory remains unknown. For now, clear evidence of a drug-induced neuropathological mechanism has not been demonstrated, and the criteria required to substantiate a causal relationship has not been fulfilled.

Z-drugs are associated with NREM Parasomnias (e.g. sleepwalking, sleep driving), with Zolpidem being the most strongly associated.22 Whilst sleepwalking is generally innocuous, it can result in injury to the sleep-walker and to others.23,24 The product information for Zolpidem cautions that sleepwalking may occur when Zolpidem is combined with alcohol, other CNS depressants, and when used at doses greater than 10mg (i.e. the maximum recommended dose). It would appear that the incidence of sleepwalking is not dependent on age, sleepwalking history or medical history. However, higher rates are seen in patients taking Zolpidem combined with other psychotropics (e.g. antidepressants and antipsychotics).22 When prescribing Z-drugs, it is therefore important to warn all patients of the potential risk of NREM Parasomnias, to monitor for them, and to consider an alternate hypnotic if they occur.

The risk of fatality from Z-drug mono-overdose via respiratory or nervous system depression appears non-existent.25 It is their combination with other suppressants, such as alcohol, opioids and muscle relaxants which increase the risk. As for the other newer safety concerns regarding Z-drugs e.g. risk of cancer, infection, pancreatitis and increased mortality etc, no studies demonstrating causation have been published. As one is innocent until proven guilty, epidemiological association does not equate to causation.

Minimising costs

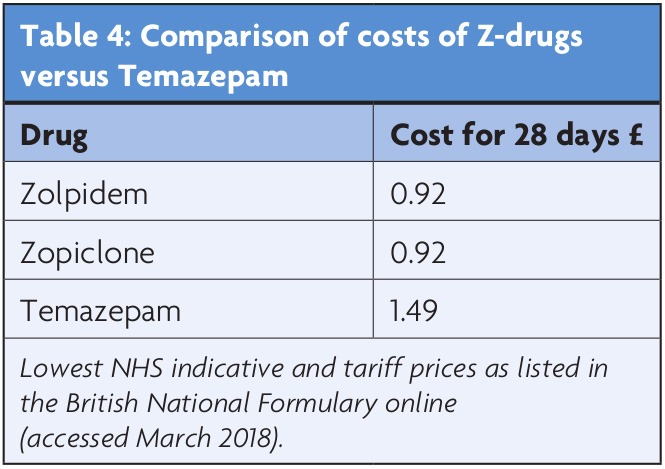

Insomnia is estimated to cost the US economy $63-90bn a year.26,27 These costs include direct treatment costs, such as physician encounters and prescriptions, as well as indirect costs, such as consumption of medical services, increased accident risk, and lost workplace productivity. One study suggested the latter is accountable for up to 76% of the economic burden.28 There are no comparable figures for the UK, though one study estimated insufficient sleep (characterised as sleeping less than six hours per night) as costing the UK $50bn a year.29 The manufacturers of the Z-drugs submitted economic models to the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) which concluded that any additional acquisition costs (over and above traditional benzodiazepines) would be reduced by lower consumption of other healthcare resources and/or lead to an improvement in health outcomes as a result of decreased dependence or reduced residual effects.30 NICE rejected their economic models, based on the “lack of compelling evidence on any clinically useful differences between the Z-drugs and the shorter-acting benzodiazepine hypnotics”, and concluded that the lowest cost drug should be used.30 As Table 4 highlights, their advice would currently be in favour of the Z-drugs. Despite any arguments made, there is currently a paucity of published economic evidence to support NHS decision making in this area. Economic evaluations alongside randomised clinical trials would need to be conducted in order to build a clinical and economic evidence base to inform decision making.

Respecting patient choice

Despite guidelines advocating the short-term use of Z-drugs, many of us will have patients who require them for longer than the licensed maximum period of four weeks. Sadly, these patients are often made to feel like drug-seeking pariahs.31 The associated anxiety and guilt they feel from requesting additional prescriptions, often compounds the torture of the night; another perpetuating factor to drive their insomnia.

Insomnia is a real and frequently chronic condition. Its associated adverse quality of life effects (akin to significant depression32), and the risks it poses to mental health, are often minimised by health care professionals.31 Z-drugs offer one potential treatment solution, and whilst every effort should be made to encourage patients to engage in a non-medication alternative i.e. CBT-I, there will be a proportion for whom this treatment is not desirable, suitable, or effective. Many patients are happy with their Z-drug treatment, and show no signs of drug misuse or of developing tolerance or dependency – in their eyes, if it’s not broken why fix it? In 2005, the FDA approved two Z-drugs (Eszopiclone and Zolpidem extended release; both unavailable in the UK) without placing restrictions on their therapeutic time-line. Perhaps as our knowledge of the safety profile of these hypnotics increases, so too will our confidence to question current guidelines.

Despite media scaremongering of a Z-drug epidemic, one UK study showed that 0.69% of 18 to 80 year-olds were taking benzodiazepines and Z-drugs for more than one year.33 When applied to nationwide patient numbers, the British Medical Association equated this to between 265-295,000 patients using long term benzodiazepines and Z-Drugs.34 As a comparison, in 2015, it was estimated that 6% of the UK population (which was extrapolated to 950,500 people) had been using over-the-counter painkillers for more than a year.35

As with any other medication, once a Z-drug is initiated it should be regularly reviewed, and monitored for signs of emerging misuse, tolerance or dependency. Prescribing higher than the maximum recommended dose of a Z-drug is not advised. If a Z-drug at the maximum dose looses efficacy, then a re-assessment (including for co-morbid sleep, physical and mental health disorders) is warranted. The Z-drug should be withdrawn slowly (as to avoid rebound insomnia), and replaced (if appropriate) with an alternative hypnotic. These alternatives are often low-dose sedative anti-depressants or anxiolytics, where there are parallels in our knowledge deficits regarding their long-term use and safety.36

Several authors have suggested that Z-drugs have a lower risk and misuse potential when compared to benzodiazepines.37,38 It has been postulated that this is because of their lower affinity for the alpha-2 subtype. However, careful consideration should be given before initiating Z- drugs to patients with a past history of alcohol or drug misuse or dependency, as this may increase the risk. In monitoring for potential misuse, using a Z-drug for purposes other than insomnia (e.g. as an anxiolytic), and seeking more before a prescription has expired should raise concern. In relation to the latter, it is advisable that there is only one prescription source, and it is often safer that this is undertaken by the GP, who will have more regular patient contact, as well as a more holistic over-view of their health and social difficulties.

Future directions

Rather than scaremongering and media dictates, long-term efficacy, safety, quality of life and economic studies are needed to guide our prescribing of Z-drugs for insomnia. Moreover, these studies should include “special populations”, such as the elderly, and those with chronic medical and psychiatric co-morbidities. Such studies will be challenging, but they should be approached with an open mind; lies may not be like sleeping pills.

References

- Barber N. What constitutes good prescribing? BMJ 1995;310:923-5

- Stepanski EJ and Wyatt JK. Use of sleep hygiene in the treatment of insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2003;7:215-25.

- Lamberg L. Despite effectiveness, behavioural therapy for chronic insomnia still under used. JAMA 2008;300:2474- 75.

- van Straten A and Cuijpers P. Self-help therapy for insomnia: A meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2009;13:61-71.

- Espie CA, Kyle SD, Williams C et al. A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Insomnia Disorder Delivered via an Automated Media-Rich Web Application. Sleep 2012;35:769-81.

- Jacobs GD, Pace-Schott EF, Stickgold R et al. Cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy for insomnia; a randomized controlled trial and direct comparison. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004;164:1888-96.

- Vincent N. and Lionberg C. Treatment preference and patient satisfaction in chronic insomnia. Sleep 2001;11:488-96.

- Riemann D, Perlis ML. The treatments of chronic insomnia: a review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioural therapies. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:205-14.

- Morin CM, Colecchi C, Stone J, et al. Behavioral and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1999;281:991-9.

- Gorgels WJ, Oude Voshaar RC, Mol AJ et al. Discontinuation of long-term benzodiazepine use by sending a letter to users in family practice: a prospective controlled intervention study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;78:49-56.

- Voshaar RC, Wim JM, Gorgels WJ et al. Tapering off longterm benzodiazepine use with or without group cognitive − behavioural therapy: three-condition, randomised controlled trial. BJP 2003;182:498-504.

- Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults. JAMA 2006;295:2851-8.

- Mitchell MD, Gehrman P, Perlis M et al. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:40.

- Leufkens TRM and Vermeeren A. Zopiclone’s residual effects on actual driving performance in a standardized test: a pooled analysis of age and sex effects in 4 placebo-controlled studies. Clin Ther 2014;36:141-50.

- Vermeeren A, Vuurman EFPM, Leufkens TRM, et al. Residual effects of low-dose sublingual zolpidem on highway driving performance the morning after middle-ofthe- night use. Sleep 2014;37:489-96.

- Bocca M-L, Marie S, Lelong-Boulouard V, et al. Zolpidem and zopiclone impair similarly monotonous driving performance after a single nighttime intake in aged subjects. Psychopharmacology 2011;214(3):699-706.

- ICADTS. ICADTS drug list–July 2007. 2007:1–15. http://www.icadts.nl/reports/medicinaldrugs2.pdf

- Glass J, Lanctôt KL, Hermann N et al. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ 2205;331:1169.

- Avidan AY, Fries BE, James ML, et al. Insomnia and hypnotic use, recorded in the minimum data set, as predictors of falls and hip fractures in Michigan nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:955-62.

- Chen PL, Lee WJ, Sun WZ et al. Risk of Dementia in Patients with Insomnia and Long-term Use of Hypnotics: A Population-based Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e49113.

- Shih HI, Lin CC, Tu YF et al. An increased risk of reversible dementia may occur after zolpidem derivative use in the elderly population: a population-based case–control study. Medicine 2015;94:e809.

- Stallman HM, Kohler M and White J. Medication induced sleepwalking: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2018;37:105-13.

- The Times. News in brief: £1.3m for window fall sleepwalker. London:The Times; Nov 14, 2000.p8.

- Poceta JS. Zolpidem ingestion, Automatisms, and Sleep Driving: A Clinical and Legal Case Series. J Clin Sleep Med 2011;7(6):632-8.

- Ben Tsutaoka P. Chapter 31. Benzodiazepines. In: Olson KR, editor. Poisoning and drug overdose, 6e. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Walsh JK, Engelhardt CL. The direct economic costs of insomnia in the United States for 1995. Sleep1999;22:S386-93.

- Stoller MK. Economic effects of insomnia. Clin Ther 1994;16:873-97.

- Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M et al. The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep 2009;32:55-64.

- Hafner MS, Stepanek M, Taylor J, et al. Why sleep matters – the economic costs of insufficient sleep: A cross-country comparative analysis. RAND Corporation 2016. https://www.rand.org/ pubs/research_reports/RR1791.html.

- https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta77/chapter/ 4-Evidence-and-interpretation#cost-effectiveness

- Days JV, Apekey TA, Tilling M, et al. Patients’ and clinicians’ experiences of consultations in primary care for sleep problems and insomnia: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e180-e200.

- Idzikowski C. Impact of Insomnia on Health-Related Quality of Life. PharmacoEconomics 1996;10:15.

- Davies J, Rae TC and Montagu L. Long-term benzodiazepine and Z-drugs use in the UK: a survey of general research. British Journal of General Practice 2017;67:e:609-e613.

- https://www.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/ policy-and-research/public-and-population-health/ prescribed-drugs-dependence-and-withdrawal

- http://prescribeddrug.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/ Opioid_painkiller_dependency_final_report_Sept_201.pdf

- Roth T. Use of low-dose sedating antidepressants versus benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics in treating insomnia. Medscape Internal Medicine 2005;7(2) https:// http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/508820https:// http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/508820

- Shahid A, Chung SA, Phillipson R et al. An approach to long-term sedative-hypnotic use. Nature and Science of Sleep 2012;4:53-61.

- Kramer M. Hypnotic medication in the treatment of chronic insomnia: non nocere! Doesn’t anyone care? Sleep Med Rev 2000;4:529-41.