Abstract

Epilepsy and sleep have a close association and a two way interaction. Recognising this allows for a greater awareness of the importance of good quality sleep in epilepsy patients with potential benefits on seizure control and quality of life. This article reviews this complicated but fascinating area addressing diagnostic issues, the effects of epilepsy and its treatments on sleep, the effects of sleep disorders on epilepsy concluding with some practical advice on assessment.

Introduction

Sleep and epilepsy are intimate bedfellows, having an impact on each other and adversely affecting quality of life and daytime performance.1 Sleep has an important role in memory consolidation.2 Sleep deprivation impairs this process3 and epilepsy can upset this delicate balance.4 Sleep disorders are up to three times as common in epilepsy5 and can be a major contributor to refractory seizures,6 poorer quality of life7 and possibly SUDEP.8 Recognition of the comorbid sleep disorder and successful treatment can lead to significant improvements in seizure control.9 Many patients with epilepsy have seizures in sleep, some exclusively so. Often diagnosis is difficult due to incomplete histories from sleep partners. Even when telemetry facilities are available, data can be difficult to interpret and EEG is not always diagnostic.10 To add to this complexity, epilepsy treatments often have impact on sleep. Understanding this complex relationship can lead to better treatment outcomes for patients. This review will begin with diagnostic issues, moving on to the effects of epilepsy and its treatments on sleep, the effects of sleep disorders on epilepsy and concludes with practical advice on assessment.

Epilepsy syndromes cosely associated with sleep

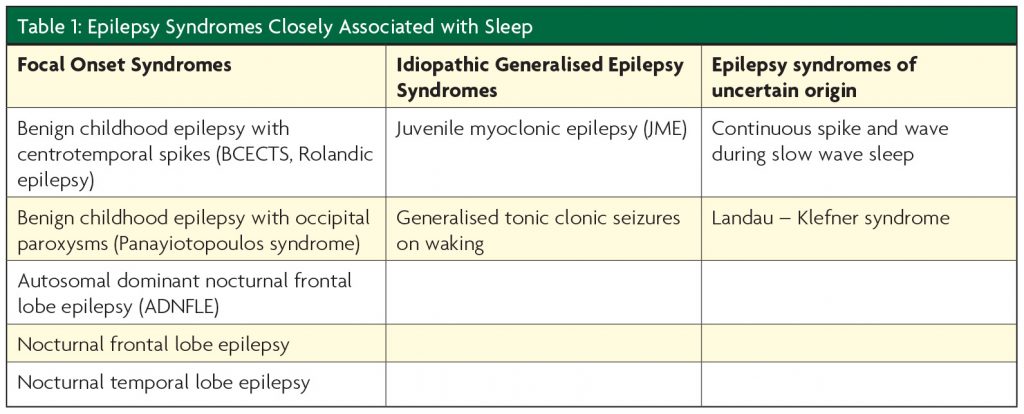

There are a small number of epilepsy syndromes which are predominantly or exclusively associated with sleep (Table 1). Seizures arising from sleep are almost always of focal onset. These include the childhood onset syndromes of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BCECTS, Rolandic epilepsy), benign childhood epilepsy with occipital paroxsysms (Panayiotopoulos syndrome) and the frontal lobe epilepsy syndromes (including autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy ADNFLE). Idiopathic generalised epilepsy syndromes (IGE) such as juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) and generalised tonic clonic seizures on waking arise shortly before or after sleep onset but not from a sleep state.

Diagnosing paroxysmal nocturnal events

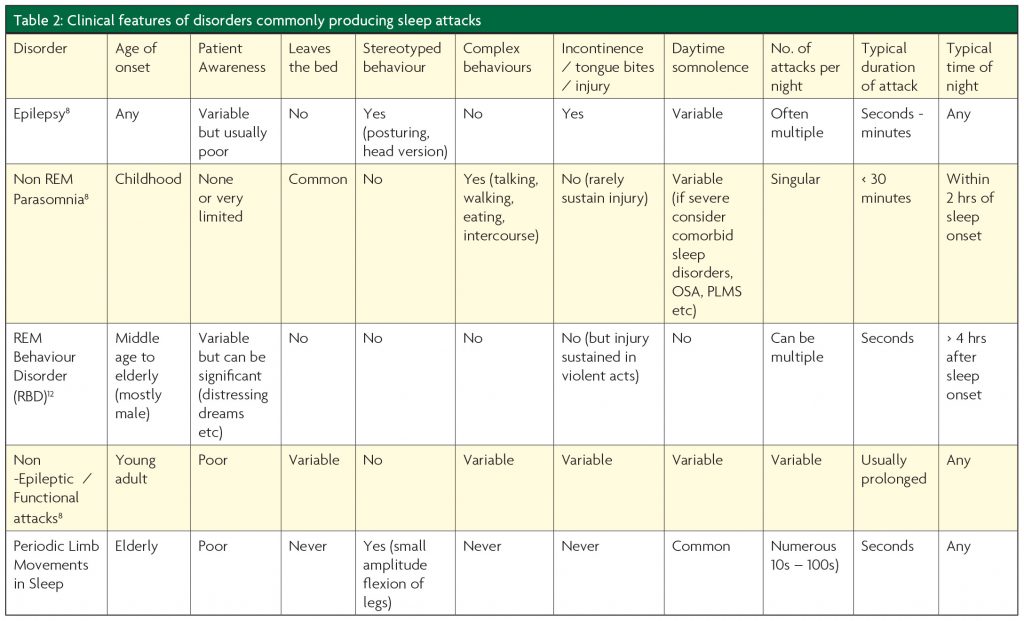

Table 2 summarises clinically important details which help in differentiating epilepsy from other sleep disorders. Derry et al (2006 & 2009) have produced very useful clinical tools to help differentiate nocturnal seizures from other sleep disorders with diagnostic accuracy up to 94%11,12,8 however comorbidity is common13 and an awareness of the characteristic features of the more common conditions enhances the history taking process. During nocturnal seizures patients rarely leave the bed space, episodes are often brief and stereotyped and can cluster throughout the night (Figure 1). Incontinence, tongue trauma and seizures during daytime wakefulness are strong pointers. Postictal symptoms on waking such as generalised aching, headache and amnesia of the preceding day’s events are strongly associated.

Parasomnia episodes are seen in either rapid eye movement (REM) or non-REM (nREM) sleep. REM parasomnia (REM behaviour disorder (RBD) is almost exclusively seen in elderly subjects with a male predominance, often associated with alpha synucleonopathies.14 Dream enactment occurs due to a lack of muscle atonia during REM sleep. Episodes occur late in the sleeping period where a higher concentration of REM sleep is seen. Patients often recall their dreams, behaviour is often violent and episodes are repeated each night. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine suggests RBD is diagnosed with polysomnography (PSG) as it can sometimes be dif cult to differentiate it from epilepsy on the history alone.15

nREM parasomnias generally arise in childhood, they are less frequent and usually singular during the early part of a sleeping period. Patients are more often amnesic to the event however, some recollection of the later stages of events is often reported due to awakening, often in a confused state. Injury is rare, behaviour is often complex and episodes can be prolonged but usually not more than 30 minutes. Excessive daytime somnolence (EDS) is generally not a direct consequence of nREM parasomnias but if severe one should consider comorbid sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS).

Night terrors and confusional arousals

Differentiating between these two types of common nREM parasomnias often causes difficulty. Night terrors are exclusively a paediatric condition and don’t persist into adulthood. Although deeply asleep, the child appears awake and is inconsolably terrified, often screaming loudly. Events can last up to one hour but they are not remembered. Confusional arousals occur in adulthood when an abrupt but incomplete awakening occurs from slow wave sleep (SWS), often associated with distressing dreams which can be recalled, leading to confusion and sometimes injury.16 Diagnostic difficulty can arise when the arousal is due to a short seizure and the confusion due to postictal phenomena.

The effects of epilepsy on sleep

The effects and consequences of epilepsy on the sleep EEG

Objective PSG assessments show that interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs), increase in sleep17 especially in N3 nREM sleep, although seizures seem to predominate in lighter nREM sleep.18 Nocturnal seizures lead to reductions in REM sleep and increases in nREM sleep. These changes are also seen when a wakeful seizure has occurred the previous day.19 Seizure types have differing relationships with sleep with focal epilepsies being more likely to disrupt sleep than IGE. Even in seizure free states, interictal temporal lobe epileptic discharges seem to disrupt sleep when compared with frontal lobe epilepsy (FLE) and IGE. Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) correlates with worse sleep ef ciency and increased stage shifts and awakenings. Despite this, frontal lobe seizures are seen more commonly in sleep than temporal lobe seizures.20 Uncontrolled epilepsy in sleep can lead to memory impairments4 and excessive daytime somnolence (EDS).5

The effect of epilepsy treatments on sleep

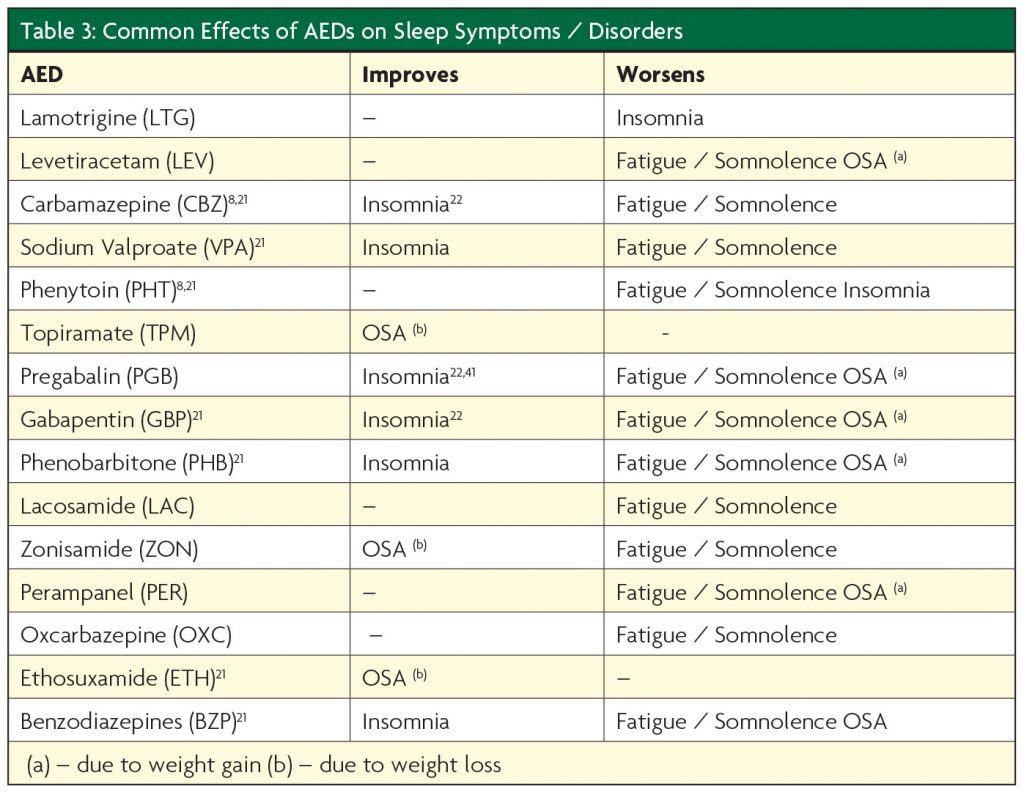

AEDs (Table 3) and epilepsy surgery can affect sleep however the particular effects can be unpredictable.

AEDs

Few studies have been conducted in this complex area. Those which have are limited by short duration and inadequate controls for seizure types and polypharmacy. It appears that AEDs can improve sleep, however it is uncertain if this is due to improved seizure control or independent sleep consolidation.8 Unfortunately, AEDs commonly produce daytime fatigue and at higher doses excessive daytime somnolence (EDS).23 This can be an advantage in patients with insomnia. Some AEDs are associated with significant weight gain which can lead to OSA. Care must be taken when using sedating drugs such as the benzodiazepines (BZPs) in patients who may be prone to sleep disordered breathing as apnoeic episodes may increase.24 Care should be taken when labeling EDS as a side-effect of AEDs as this risks under interpreting the disruptive effects of unrecognised nocturnal seizures or co-morbid sleep disorders. Polysomnography (PSG) may be required to differentiate between the two.

The effects of AED withdrawal on sleep must also not be overlooked. Withdrawal of a sedating drug may lead to reductions in sleep,25 withdrawal of mood stabilising AEDs (i.e. VPA, CBZ, LTG, TPM) may lead to worsening depression and anxiety all of which can precipitate insomnia and nREM parasomnias. Withdrawal of TPM can lead to weight gain which may precipitate OSA.

Chronopharmacology

Chronopharmacology holds great potential when applied to the management of epilepsy; it recognises that circadian rhythms exist in absorption and metabolism of drugs. For example, it has been recognised that without changing the total daily dose of PHT and CBZ in epilepsy patients, serum levels increase and seizure control improves by administering proportionally higher doses at 2000 hrs compared with the morning.26 This suggests that great bene ts can be achieved by prescribing higher doses of AEDs later in the day.

Epilepsy surgery

Resective epilepsy surgery is now widely used to treat refractory epilepsy. However, only one study of 17 patients has evaluated sleep pre and post operatively using PSG. Although no overall benefit was seen, patients who attained better post operative seizure control had greater improvements in total sleep times and arousals.27 Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) has shown increases in SWS and nocturnal sleep latency in a study of 15 children with refractory epilepsy.28 However, in adult populations it can lead to deterioration in sleep disordered breathing in up to 31% of patients29 thus changes in snoring and EDS should be closely monitored post VNS insertion. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is now a recognised epilepsy surgery technique however it may have deleterious effects on sleep as there is a small amount of evidence to suggest that anterior thalamic nucleus DBS has been found to increase electroclinical arousals on average 3.3 times more frequently during stimulation periods compared to non-stimulation periods in a study of 9 patients.30

The effects of sleep disorders on epilepsy

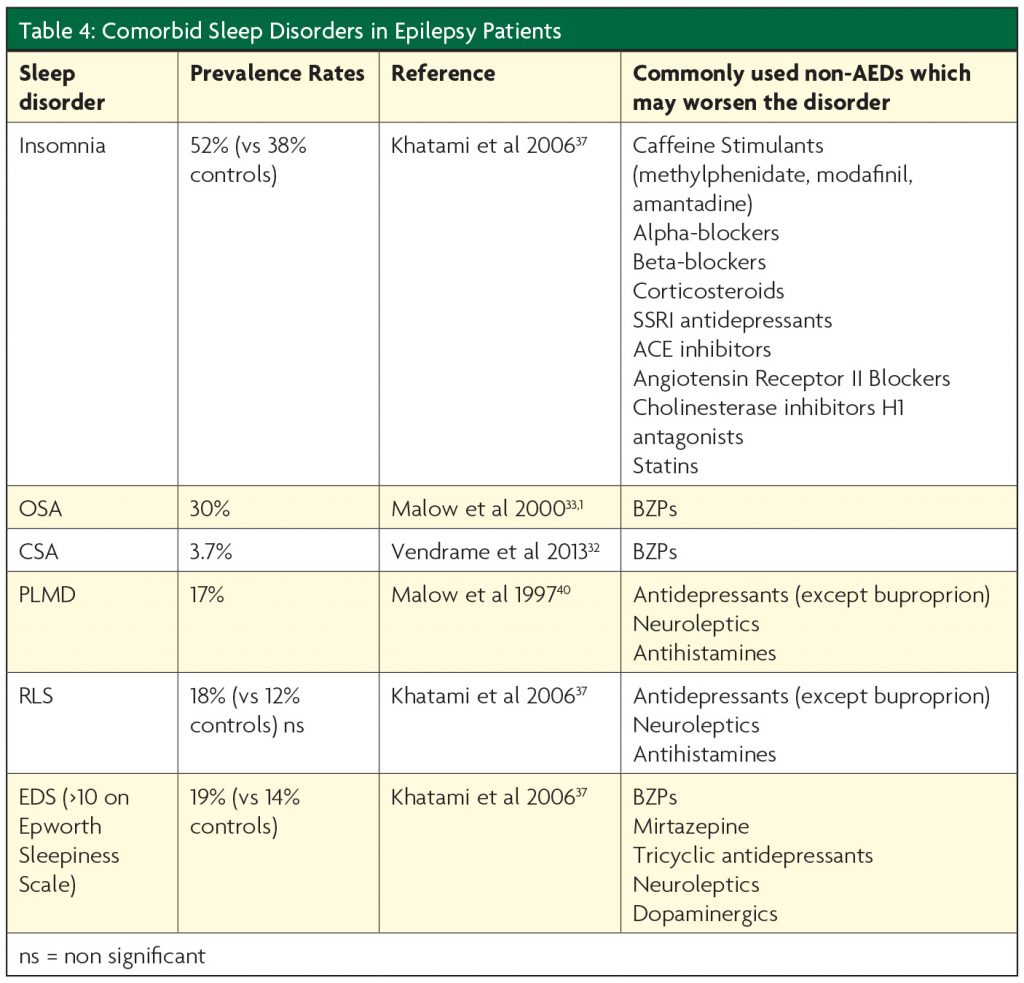

Sleep disorders are up to three times as common in patients with epilepsy compared with controls.5 Sleep deprivation is often associated with an increase in IEDs and poorer epilepsy control31 with 77% of JME patients reporting more seizures when sleep deprived.32 AEDs are associated with weight gain,33 and mental health disorders34 and both of these conditions predispose to sleep disorders. OSA is often caused or worsened by increases in the BMI and is known to have prevalence rates up to 30% in epilepsy populations33 and is associated with worsening seizure control.6 TLE has a greater association with OSA than extra temporal seizures.35 Management of OSA with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) produces improvements in epilepsy control with seizure freedom seen in almost 20% in a randomised controlled trial of 68 using therapeutic vs sham CPAP.7 Impressive responder rates (>50 % seizure reduction) have also been reported in trials of CPAP for OSA in epilepsy subjects (OR 32.2).36 Mood disturbance is also very prevalent in epilepsy patients.34 Sleep disorders are commonly associated with these mental health problems. Concurrent use of antidepressants is common, thus an awareness of the effects of these drugs is required when evaluating sleep complaints in epilepsy patients to ensure their contribution is not overlooked (Table 4), in particular an awareness of the potential for precipitation of RBD, RLS and PLMD. RBD can be mistaken for epilepsy and can be effectively treated with removal of the antidepressant or the use of melatonin. RBD, restless leg syndrome (RLS) and periodic limb move- ment disorder of sleep (PLMD) are also commonly precipitated by antidepressant and neuroleptic drugs however RLS and PLMD occur in a primary form in the absence of pharmacological triggers and can significantly disrupt the quality of sleep although the evidence available suggests they are no more common in epilepsy subjects compared with controls.37,38 There is no published evidence on the impact of treating RLS / PLMD on seizure control however this should be considered good practice.

Conclusions

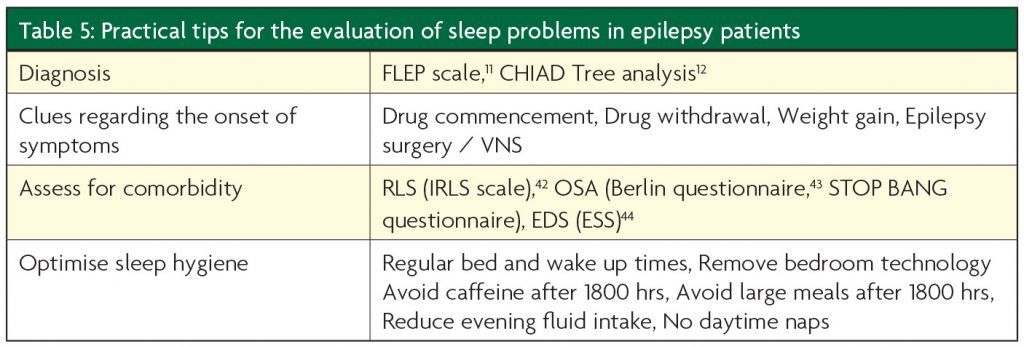

Epilepsy and sleep and its disorders are very closely associated and improvements in the recognition and management of either will have beneficial effects on the other (see Table 5 for practical tips on clinical assessment). Research in this field is still in its infancy compared with other neurological conditions, however greater awareness and investment promises much for epilepsy patients.

References

- Grigg-Damberger MM, Foldvary-Schaefer N. Primary sleep disorders in people with epilepsy: clinical questions and answers. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2015; Jan;24(1):145-76.

- Wamsley EJ, Stickgold R. Memory, Sleep and Dreaming: Experiencing Consolidation. Sleep Med Clin. 2011;1;6(1):97-108.

- Stickgold R, James L, Hobson JA. Visual discrim- ination learning requires sleep after training. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(12):1237-8.

- Urbain C, Di Vincenzo T, Peigneux P, Van Bogaert P. Is sleep-related consolidation impaired in focal idiopathic epilepsies of childhood? A pilot study. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22(2):380-4.

- de Weerd A, de Haas S, Otte A, Trenité DK, van Erp G, Cohen A, de Kam M, van Gerven J. Subjective sleep disturbance in patients with partial epilepsy: a questionnaire-based study on prevalence and impact on quality of life. 2004;45(11):1397-404.

- Chihorek AM, Abou-Khalil B, Malow BA. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with seizure occurrence in older adults with epilepsy. 2007;6;69(19):1823-7.

- Kwan P, Yu E, Leung H, Leon T, Mychaskiw MA. Association of subjective anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance with quality-of-life ratings in adults with epilepsy. 2009;50(5):1059-66.

- Derry CP, Duncan S. Sleep and epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;26(3):394-404.

- Malow BA, Foldvary-Schaefer N, Vaughn BV, Selwa LM, Chervin RD, Weatherwax KJ, Wang L, Song Y. Treating obstructive sleep apnea in adults with epilepsy: a randomized pilot trial. 2008;19;71(8):572-7

- Provini F, Plazzi G, Tinuper P, Vandi S, Lugaresi E, Montagna P. Nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy. A clinical and polygraphic overview of 100 consecutive cases. 1999;122 ( Pt 6):1017-31.

- Derry CP1, Davey M, Johns M, Kron K, Glencross D, Marini C, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF. Distinguishing sleep disorders from seizures: diagnosing bumps in the night. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(5):705-9.

- Derry CP, Harvey AS, Walker MC, Duncan JS, Berkovic SF. NREM arousal parasomnias and their distinction from nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy: a video EEG analysis. 2009;32(12):1637-44.

- Manni R, Terzaghi M. Comorbidity between epilepsy and sleep disorders. Epilepsy Res. 2010;90(3):171-7.

- Iranzo A, Santamaría J, Rye DB, Valldeoriola F, Martí MJ, Muñoz E, Vilaseca I, Tolosa E. Characteristics of idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder and that associated with MSA and PD. 2005;26;65(2):247-52.

- Aurora RN, Zak RS, Maganti RK, Auerbach SH, Casey K, Chowdhuri S, Karippot A, Ramar K, Kristo DA, Morgenthaler TI. Best Practice Guide for the Treatment of REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD) Standards of Practice Committee. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;15; 6(1): 85–95.

- Derry CP, Duncan JS, Berkovic SF. Paroxysmal motor disorders of sleep: the clinical spectrum and differentiation from epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47(11):1775-91.

- Parrino L, Smerieri A, Spaggiari MC, Terzano MG. Cyclic alternating pattern (CAP) and epilepsy during sleep: how a physiological rhythm modulates a pathological event. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111 Suppl 2:S39-46.

- Herman ST, Walczak TS, Bazil CW. Distribution of partial seizures during the sleep-wake cycle: differences by seizure onset site. Neurology. 2001;12;56(11):1453-9.

- Bazil CW, Castro LH, Walczak TS. Reduction of rapid eye movement sleep by diurnal and nocturnal seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(3):363-8.

- Crespel A, Coubes P, Baldy-Moulinier M. Sleep in uence on seizures and epilepsy effects on sleep in partial frontal and temporal lobe epilepsies. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111 Suppl 2:S54-9.

- Sammaritano M, Sherwin A. Effect of anticonvul- sants on sleep. Neurology. 2000;54(5 Suppl 1): S16-24.

- Jain SV, Glauser TA. Effects of epilepsy treatments on sleep architecture and daytime sleepiness: an evidence-based review of objective sleep metrics. Epilepsia. 2014;55(1):26-37.

- Foldvary-Schaefer N, Grigg-Damberger M. Sleep and epilepsy. Semin Neurol. 2009;29(4):419-28.

- Guilleminault C. Benzodiazepines, breathing, and sleep. Am J Med. 1990;2;88(3A):25S-28S.

- Schmitt B, Martin F, Critelli H, Molinari L, Jenni OG. Effects of valproic acid on sleep in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50(8):1860-7.

- Yegnanarayan R, Mahesh SD, Sangle S. Chronotherapeutic dose schedule of phenytoin and carbamazepine in epileptic patients. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(5):1035-46.

- Zanzmera P, Shukla G, Gupta A, Goyal V, Srivastava A, Garg A, Bal CS, Suri A, Behari M. Effect of successful epilepsy surgery on subjective and objective sleep parameters–a prospective study. Sleep Med. 2013;14(4):333-8.

- Hallböök T, Lundgren J, Köhler S, Blennow G, Strömblad LG, Rosén I. Bene cial effects on sleep of vagus nerve stimulation in children with therapy resistant epilepsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2005;9(6):399-407.

- Marzec M1, Edwards J, Sagher O, Fromes G, Malow BA. Effects of vagus nerve stimulation on sleep-related breathing in epilepsy patients. Epilepsia. 2003;44(7):930-5.

- Voges BR, Schmitt FC, Hamel W, House PM, Kluge C, Moll CK, Stodieck SR. Deep brain stimulation of anterior nucleus of thalami disrupts sleep in epilepsy patients. Epilepsia. 2015;56(8):e99-e103.

- Eriksson SH. Epilepsy and sleep. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24(2):171-6.

- da Silva Sousa P, Lin K, Garzon E, Sakamoto AC, Yacubian EM. Self- perception of factors that precipitate or inhibit seizures in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Seizure. 2005;14(5):340-6.

- Malow BA, Levy K, Maturen K, Bowes R. Obstructive sleep apnea is common in medically refractory epilepsy patients. Neurology. 2000;10;55(7):1002-7.

- FDA U Antiepileptic drugs and suicidality. 2008. Available from http:// http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/08/brie ng/2008-4372b1-01-FDA.pdf.

- Yildiz FG, Tezer FI, Saygi S. Temporal lobe epilepsy is a predisposing factor for sleep apnea: A questionnaire study in video-EEG monitoring unit. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;48:1-3.

- Pornsriniyom D, Kim Hw, Bena J, Andrews ND, Moul D, Foldvary- Schaefer N. Effect of positive airway pressure therapy on seizure control in patients with epilepsy and obstructive sleep apnea. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;37:270-5.

- Khatami R, Zutter D, Siegel A, Mathis J, Donati F, Bassetti CL. Sleep-wake habits and disorders in a series of 100 adult epilepsy patients–a prospective study. Seizure. 2006;15(5):299-306.

- Malow BA, Bowes RJ, Lin X. Predictors of sleepiness in epilepsy patients. Sleep. 1997;20(12):1105-10.

- Vendrame M, Jackson S, Syed S, Kothare SV, Auerbach SH. Central sleep apnea and complex sleep apnea in patients with epilepsy. Sleep Breath. 2014;18(1):119-24.

- Malow BA, Fromes GA, Aldrich MS. Usefulness of polysomnography in epilepsy patients. Neurology. 1997;48(5):1389-94.

- Roth T, Arnold LM, Garcia-Borreguero D, Resnick M, Clair AG. A review of the effects of pregabalin on sleep disturbance across multiple clinical conditions. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(3):261-71.

- Wunderlich GR, Evans KR, Sills T, Pollentier S, Reess J, Allen RP, Hening W, Walters AS. International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. An item response analysis of the international restless legs syndrome study group rating scale for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2005;6(2):131-9.

- Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, Chung SA, Vairavanathan S, Islam S, Khajehdehi A, Shapiro CM. Validation of the Berlin questionnaire and American Society of Anesthesiologists checklist as screening tools for obstructive sleep apnea in surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):822-30.

- Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540-5.