Abstract

Evidence demonstrates that the prevalence of hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury (TBI) is higher than previously anticipated and leads to significant morbidity. Given the prevalence of TBI, there may be a significant pool of patients with undiagnosed hypopituitarism. This places an emphasis on screening to detect the disease and treat it accordingly, as highlighted in guidance published in 2017. The review discusses hypopituitarism following TBI and analyses the potential impact of limited patient education and resources and how current working practice may impact on screening.

Summary

- Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is common and associated with significant health and social care costs

- Post traumatic hypopituitarism (PTHP) occurs in approximately a quarter of all patients with TBI and may be a transient phenomenon

- New guidance published in 2017 recommend that all persons admitted to hospital for more than forty-eight hours with TBI should have a pituitary screen three to six months following injury

- All patients admitted with TBI should be screened if symptomatic in any phase post injury

- Limited patient education and resources, problems with the primary and secondary care interface and the challenges of providing integrated care may impact access to screening for PTHP.

Introduction

The incidence of traumatic brain injury (TBI) is variable worldwide. This is most likely due to population based characteristics, fluctuations in methodological reporting and inclusion criteria but it is likely to be within the region of 200 to 235/100 000 per year based on systematic reviews of European and North American populations.1,2 In England and Wales, approximately 1.4 million patients per year attend hospital following head injury and it is the most common cause of death under the age of 40 years.3 The sequela of TBI is wide ranging and includes long-term physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments with associated disability.5 Furthermore, TBI is associated with a significant health and social care cost.6,7 Due to its impact on society it is imperative that morbidity associated with TBI is recognised and treated to reduce the burden of this common and often life changing condition.5

In recent years, there has been an increasing emphasis on hypopituitarism complicating the presentation of TBI.8,9 It is noteworthy that there is marked disparity in reporting the incidence of post-traumatic hypopituitarism (PTHP). This is, again, due to methodological variance, the use of different screening methods including static and dynamic tests and alternating interpretations of results.10 This means that the true prevalence is difficult to determine, however systematic reviews and meta-analyses have purported the figure to be in the region of 26% to 28%.10,11 Furthermore, PTHP can present years after injury underscoring the importance of effective screening.12 In 2017, the British Neurotrauma Group introduced welcome guidance regarding screening for PTHP in persons with TBI.13

Classification

The classification of PTHP can be described in accordance with anatomical definitions and in time. Firstly, anterior and posterior pituitary dysfunction has been depicted. Secondly, the temporal relationship to the initial TBI has been described.13 Presentations of PTHP can occur in the acute setting, which is most commonly considered as less than one month (but usually within seven days) after injury. The chronic phase represents the time period after four weeks.13 Isolated hormone insufficiencies are more prevalent than multiple co-existing endocrinopathies.14

Considering anterior pituitary dysfunction somatotropin and gonadotropin deficiencies are most common, followed by corticotropin and thyrotropin deficiency. The potentially life threatening nature of inadequate corticotrophins and impending adrenal insufficiency highlight the clinical relevance of screening. However, it is not only acute life threatening complications that impact on function and quality of life.14,15

With respect to posterior dysfunction, the presentation of diabetes insipidus is most common, often transient and can be challenging to diagnose. Again, there is wide variability in the reported prevalence reflecting variations in screening and the difficulties of establishing a diagnosis in the acute phase.16,17 However, the presentation is associated with other pituitary deficits16,18 and diagnosis in the early recovery phase post TBI may alert clinicians to be mindful of symptomatology consistent with anterior pituitary dysfunction presenting at a later stage in recovery.

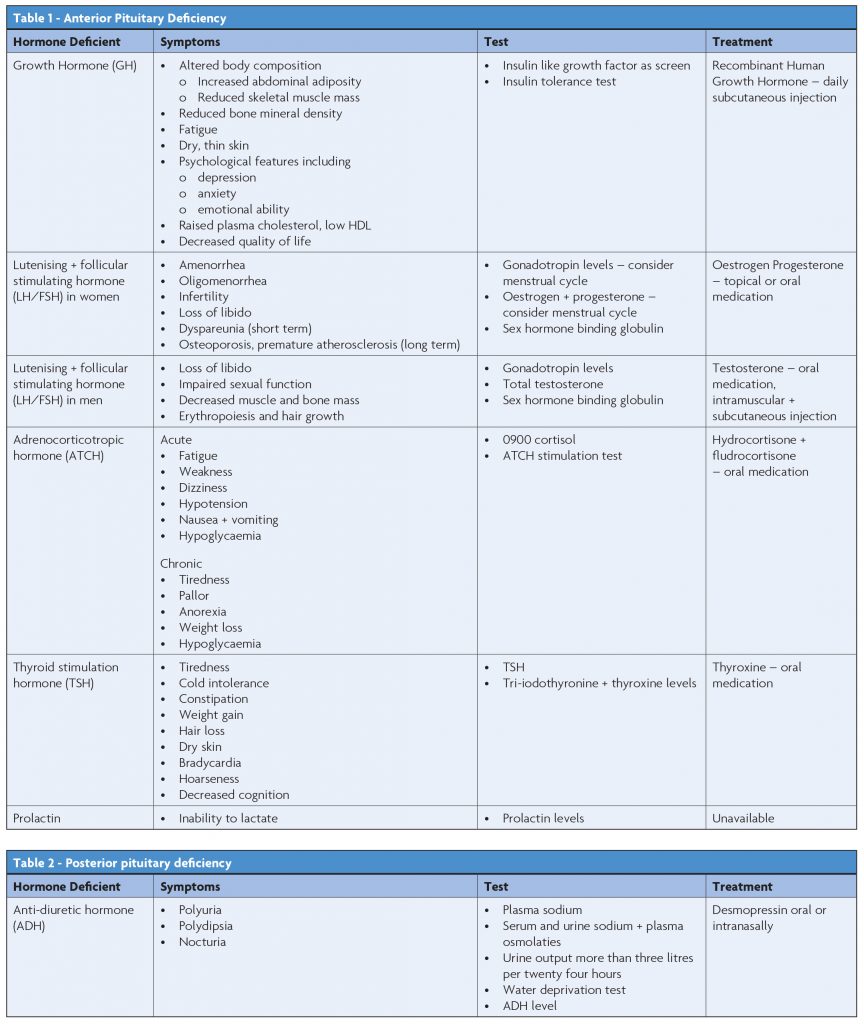

Symptoms, appropriate investigations and treatments are outlined in Table 1 and Table 2.20

Risk factors

Numerous factors are implicated as risk factors for PTHP. These include the severity of the brain injury according to the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS),20 the mechanism of injury and associated findings on cerebral imaging, pathological changes such as raised intracranial pressure and patient demographics including age and comorbidities. However, the results of analyses of these factors are variable and the evidence is inconclusive. This impacts on identifying appropriate populations to screen and research. It is noteworthy that the numbers included in studies of such populations is relatively small compared to the number of patients sustaining TBI, compounding the difficulties in interpreting results and risk factors.1-7

British Neurotrauma Group Guidance (BNGG) 2017

The BNGG provides a comprehensive review of this important topic and the recommendations seek a uniform approach to practice. Algorithms for screening in the acute and chronic phase are clear and concise.

In summary, all persons admitted to hospital with TBI, whose admission time is greater than forty eight hours should be screened for pituitary dysfunction at three to six months post injury.13 Blood tests including thyroid function tests (TFTs), 0900 cortisol, urea, creatinine, electrolytes, luteinizing hormone and follicular stimulating hormone, testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin and oestrodiol as age/sex appropriate should be performed. Due to the challenges of growth hormone testing, a referral to the Endocrinology team is proposed to assist in the diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency.13 Any person, regardless of their presenting history of TBI should be screened in the acute and chronic phase if they are symptomatic13 (see Table 1 and Table 2 for common symptoms).

Discussion in the context of current literature

It is clear from the BNGG guidance that persons appropriate for screening will present and have their care coordinated by numerous departments and specialty teams.21.22 Thus, screening will require co-ordination and appropriate communication in primary and secondary care settings. It can be anticipated that the known concerns23,24 regarding this interface will impact on screening uptake. It follows that the drive for appropriate screening in this population will need to be multi-faceted. The logistical challenge of screening all eligible patients is significant; while BNGG is targeted primarily at neurosurgeons it is relevant to all clinicians and allied heath professionals managing persons with TBI.13

International health literature highlights the importance of integrated care to deliver excellent health outcomes including in screening for and preventing disease.25,26 Here it is note-worthy that the BNGG guidance targets clinicians only. Despite this, it is plausible to argue that an integrated approach, involving allied health professionals and patients and their families/ carers, will be vital in achieving screening to diagnose PTHP.

Beyond the scope of the BNGG but arguably equally important is considering education regarding pituitary screening with respect to the patient and/or their family and carers. Recent literature has highlighted the importance of patient centred care.27,28 It could be presented that guidance aimed only at doctors’ counters this important agenda. In addition, if patients and families are educated and activated as to the importance of screening then they have the potential to drive screening uptake and the diagnosis of PTHP.29-32 Of note, in commonly searched web based resources containing information designed for patients and families experiencing TBI advice regarding the possibility of PTHP is limited. Synapse33 and The Brain Injury Association of America34 contain very finite information regarding endocrine disorders post traumatic brain injury. Only the UK based Headway website35 dedicates a whole page to PTHP. However, other sources such as the Brain Trauma Foundation36 and Brain injury Australia37 had no identifiable resources after searching the terms such as ‘endocrine’, ‘pituitary’ and ‘hormones’. In addition, only the information available on the Headway35 website referenced discussing any symptoms with a medical practitioner and stated the possibility of testing. This emphasises the importance of developing appropriate literature and resources with patients and families in mind to empower them to request screening should they experience symptoms associated with PTHP.

It is also important to consider the service implications of screening. Referrals to Endocrinology services may increase affecting overall service capacity. The BNGG recommends that Endocrinology departments should guide investigations for the diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency. This is especially pertinent when considering the presentation of growth hormone deficiency which includes fatigue and psychological disorders. Both of these are very common sequelae of TBI.38-41

Given that most common hormone deficits post TBI relate to sex and growth hormones it is prudent to examine the impact of these deficiencies on patients and consider whether a patient will meet the criteria for treatment when contemplating screening. Concerning growth hormone, which has previously been identified as improving outcomes with respect to quality of life and cognition post TBI,42-44 patients may not be eligible for treatment depending on Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) uptake of NICE guidance.45

Sexual dysfunction following traumatic brain injury is common. However, research pertaining to the medical management of this condition tends to focus on male sexual dysfunction rather than issues related to female gender. With respect to pituitary deficiency testosterone replacement should be considered,46 but akin to the situation with growth hormone access to testosterone treatment depends on eligibility.47 Thus screening may highlight deficiencies that clinicians have a limited capacity to treat.

Conclusion

The BNGG have provided commendable and welcome guidance regarding PTHP, however the practicalities of implementing screening have yet to be realised. The BNGG highlights, beyond doubt, the importance of PTHP and its detection in the recovery phase post TBI. It is now the responsibility of everyone involved in the management of TBI to implement the guidance to diagnose and manage this important condition.

References

- Tagliaferri F, Compagnone C, Korsic M. A systematic review of brain injury epidemiology in Europe. Acta Neurochir. 2006;148:255–68.

- Bruns J, Allen Hauser WE. The epidemiology of traumatic of brain injury: A review. Epilepsia. 2003;44Suppl(10):2–10,200.

- Harrison JE. (2008) Hospital separations due to traumatic brain injury, Australia 2004-05. Injury research and statistics series No 45, Cat No INJCAT 116, Adelaide.

- Ponsford J, Sloan S, Snow P. Traumatic brain injury: Rehabilitation for everyday adaptive living. Hove, UK Psychology Press, 2012.

- Australian Trauma Quality Improvement Program. ‘Australian Safety and Quality Goals for Health Care – Consultation Paper’. AusTQIP.Feb 2012. Available at: https://www. safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/National-Goals-consultation-Submission-53-National-Trauma-Research-Institute-10-Feb-2012.pdf

- Stochetti N, Zanier ER. Chronic impact of traumatic brain injury on outcome and quality of life: a narrative review. Critical Care. 2016:20 :148

- Humphreys I, Wood RL, Philips CJ. The costs of traumatic brain injury: a literature review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res: 2013;5:281-287.

- Masel BE, Urban R. Chronic endocrinopathies in traumatic brain injury disease. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1902–10.

- Tenriverdi F, Kelestimur C. Pituitary dysfunction following traumatic brain injury: clinical perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11: 1835–1843.

- Klose M, Feldt-Rasmussen U. Hypopituitarism in Traumatic Brain Injury—A Critical Note. J Clin Med. 2015;Jul; 4(7):1480–1497.

- Schneider HJ, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I, Ghigo E. Hypothalamopituitary dysfunction following traumatic brain injury and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:1429–1438.

- Yang W, Chen P, Wang T. Endocrine dysfunction following traumatic brain injury: a 5-year follow-up nationwide-based study. Scientific Reports. 2016. 6, Article number: 32987

- Tan CK, Alavi SA, Baldeweg SE. The screening and management of pituitary dysfunc-tion following traumatic brain injury in adults: British Neurotrauma Group guidance. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery and psychiatry. Available at: http://jnnp.bmj.com/ content/88/11/971.long

- Bondanelli M, Ambrosio MR, Zatelli MC. Hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005:May;152(5):679-91.

- Masel BE, Urban R. Chronic endocrinopathies in traumatic brain injury disease. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1902–10.

- Hannon MJ, Crowley RK, Behan LA. Acute glucocorticoid deficiency and diabetes insipidus are common after acute traumatic brain injury and predict mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3229–37.

- Agha A, Thornton E, O’Kelly P. Posterior pituitary dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5987–92.

- Glynn N, Agha A. Which patient requires neuroendocrine assessment following traumatic brain injury, when and how? Clin Endocrinol. 2013;78:17–20.

- Kim SY. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypopituitarism. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2015 Dec;30(4):443–455. Available at: 10.3803/EnM.2015.30.4.443

- Fernandez-Rodriguez E, Bernabau I, Castro AI. Hypopituitarism Following Traumatic Brain Injury: Determining Factors for Diagnosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2011;2:25.

- Recker A, Putt R, Broome E. Factors Impacting Discharge Destination From Acute Care for Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. Journal of Acute Care Physical Therapy. Jan 2018; Vol 9: Issue 1; 35-45.

- Zarshenas S, Tam L, Colantonio A. Predictors of discharge destination from acute care in patients with traumatic brain injury. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016694. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016694

- Sampson R, Cooper J, Barbour R, Patients’ perspectives on the medical primary–secondary care interface: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ. Open 2015;5:e008708. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008708

- Kvamme OJ, Olesen F, Samuelsson M. Improving the interface between primary and secondary care: a statement from the European Working Party on Quality in Family Practice (EQuiP). BMJ Quality & Safety 2001;10:33-39.

- World Health Organisation. Integrated Care Models: an overview. Oct 2016. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/322475/Integrated-care-models-overview.pdf

- Australian Government. Productivity Comission: Integrated Care. Supporting paper no. 5: Aug 2017. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/322475/ Integrated-care-models-overview.pdf

- The Australian Commission on safety and quality in health care; Patient Centred Care: Improving quality and safety through partnerships with patients and consumers: 2011. Available at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/PCC_ Paper_August.pdf

- The health foundation. Personal care made simple. Oct 2014. Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/PersonCentredCareMadeSimple.pdfhttps://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/PersonCentredCareMadeSimple.pdf

- Richmond group of charities: ’From Vision to Action: Making patient–centred care a reality’. King’s Fund, 2012; Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/ field_publication_file/Richmond-group-from-vision-to-action-april-2012-1.pdf

- Fischer M, Ereaut G. When doctors and patients talk: making sense of the consultation. The Health Foundation; June, 2012: Available at: http://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/ files/WhenDoctorsAndPatientsTalkMakingSenseOfTheConsultation.pdf

- Newbonner L, Chamberlain R, Borthwick R. Sustaining and spreading self management support. The Health Foundation; Sept 2013; Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/sites/ default/files/SustainingAndSpreadingSelfManagementSupport.pdf

- Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Affairs. 2013 Feb;32;2: 207-14

- Synapse; Website copyright 2018; Getting the facts. Available at: http://synapse.org.au/ information-services/some-of-the-main-difficulties-that-can-affect-people-after-brain-in-jury.aspxhttp://synapse.org.au/ information-services/some-of-the-main-difficulties-that-can-affect-people-after-brain-in-jury.aspx

- Brain Injury Association of America; Website copyright 2018. Adults and Brain Injury: Impact on health. Available at: https://www.biausa.org/brain-injury/about-brain-injury/ adults-what-to-expect/adults-brain-injury-impact-on-healthhttps://www.biausa.org/brain-injury/about-brain-injury/ adults-what-to-expect/adults-brain-injury-impact-on-health

- Headway: The Brain Injury Association. Hormonal Imbalances After Brain Injury. Website copyright 2018: Available at: https://www.headway.org.uk/about-brain-injury/individuals/ effects-of-brain-injury/hormonal-imbalances/

- The Brain Trauma Foundation. Website copyright 2018: Available at: https://www. braintrauma.org/about

- Brain Injury Australia: Website copyright 2016: Available at: https://www.braininjuryaustralia.org.au

- Cantor J, Ashman T, Gordon,W. Fatigue After Traumatic Brain Injury and Its Impact on Participation and Quality of Life. Journal: Jan-Feb 2008; Vol 23; Iss 1; pg 41–51.

- Mollayeva T, Kendzerska T, Mollayeva S. A systematic review of fatigue in patients with traumatic brain injury: the course, predictors and consequences. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014 Nov;47:684-716.

- Morton MV, Wehman P. Psychosocial and emotional sequelae of individuals with traumatic brain injury: a literature review and recommendations. Brain Injury. Vol 8;1995: Issue 1; 81-92.

- Mcallister TW. Neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury: evaluation and management. World Psychiatry. 2008 Feb;7(1):3–10.

- Walter M, High Jr, Briones-Galang M, Clark JA. Effect of Growth Hormone Replacement Therapy on Cognition after Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010;Vol 27;No 9.

- Moreau OK, Cortet-Rudelli C, Yolli E, Merlen E. Growth Hormone Replacement in Patients After Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013 Jun 1;30(11):998-1006.

- Kelly DF, Levin H, Swimmer S Dusick JR. Neurobehavioural and quality of live changes associated with growth hormone insufficiency after complicated mild, moderate or severe traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2006;Vol.23, No.6.

- National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Human growth hormone (somatropin) in adults with growth hormone deficiency: TA64. Published 2003: Available at: https://www.nice. org.uk/guidance/ta64/chapter/1-Guidance

- PM&R Knowledge NOW. Sexual dysfunction in acquired brain injury. American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; Copyright 2018; Available at: https://now.aapmr. org/sexual-dysfunction-in-acquired-brain-injury-abi/

- British Society for Sexual Medicine. BSSM guideline on adult testosterone deficiency. Published Jan 2018: Available at: https://www.guidelines.co.uk/mens-health/bssm-guide-line-on-adult-testosterone-deficiency/453888.article