Abstract

Vestibular migraine is an under-diagnosed but increasingly recognised neurological condition that causes episodic vertigo, associated with migrainous features. Making a diagnosis of VM relies on a clinical history, including the presence of recurrent episodes of vertigo or dizziness, on a background of migraine headaches, and associated migraine features that accompany the vestibular symptoms. It is the most common cause of spontaneous (non-positional) episodic vertigo, affecting up to 1% of the population, but remains under-diagnosed outside specialist centres, partly due to an absence of diagnostic biomarkers. Its pathophysiology remains poorly understood, and there is a paucity of high-quality treatment trials. Here we review the clinical features of vestibular migraine, highlight current theories that account for vestibular symptoms, and outline treatment guidelines.

Vestibular migraine (VM) is a syndrome of episodic recurrent vertigo1 or dizziness2 in patients with a current or history of migraine. Previously known as migraine-associated vertigo, migraine-associated dizziness, migraine-related vestibulopathy, migrainous vertigo, the term vestibular migraine perhaps best emphasises the prominent vestibular symptoms upon a background of migraine [1]. In 2012, the International Headache Society and the Barany Society representing the international neuro-otological community published a first consensus on diagnostic criteria for VM (Table 1) [1].

VM remains under-recognised outside specialist centres, however – only 2% of patients suspected to have VM by non-specialists whereas 20% were later diagnosed as VM by specialists [2]. In the general population, the lifetime prevalence of definite VM has been estimated to be 0.98% [3]. Another population-based study reported a 1-year prevalence of 2.7% [4].

Whether VM and migraine are distinct entities or whether these are two sides of the same coin remains an area of contention. Dizziness and vertigo may be found in up to 30% of people with migraine but a definite diagnosis of VM can be made in 10-21% of migraineurs [5,6]. VM can occur at any age with mean age of onset in middle age and a reported female to male ratio as high as 5:1 [7,8]. Migraine headaches usually precede the onset of vertigo episodes by some years, and typical migraine attacks may be replaced by vestibular episodes (especially in postmenopausal women) [8]. In children, it has been suggested that benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood is an early manifestation of VM [9].

Pathophysiology

Current models of VM pathophysiology are based on evolving theories of migraine, such as activation and sensitisation of trigeminovascular pathways, as well as brain stem and diencephalic nuclei [10,11]. Based on neurophysiological data, thalamocortical dysrhythmia (TCD) – altered rhythmic activity between thalamus and cortex leading to abnormal information processing – is also considered key to migraine pathophysiology [12,13]. Imaging studies have showed increased activity in the thalamus – known to participate in multimodal sensory sensitisation [14] – during vestibular stimulation in patients with VM [15]. A long-standing hypothesis suggests that VM episodes result from spreading depolarisation [16], akin to ‘visual aura’, but this cannot account for the more prolonged episodes of dizziness or vertigo commonly seen in VM.

From a molecular perspective, descending pathways from the monoaminergic nuclei control the sensory trigeminal unit, and several neuropeptides, such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), have essential roles in the activation mechanisms of the trigeminovascular pathways [17]. A differential proinflammatory signature in VM (namely elevated IL-1β, CCL3, CCL22, and CXCL1 levels) appears to differentiate VM from other vestibular disorders such as Ménière’s disease [18].

VM, similar to migraine headache, is commonly familial and is widely assumed to have a genetic susceptibility, with combined epigenetic, and environmental contributions [19].

Clinical features

Triggers

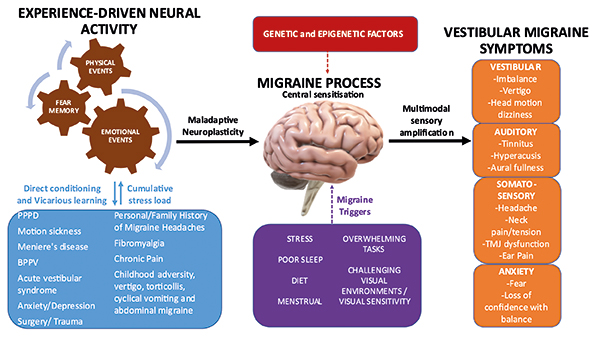

In one of the largest studies to investigate triggers in 1027 migraineurs, the commonest trigger was emotional stress (79.7%) [20]. Others have identified sleep disorders (oversleep, lack of sleep, or change in sleep pattern) to be a trigger in 81% [21], but these studies did not include VM as a specific subgroup. A history of anxiety and depression has also been associated with a significantly increased risk of developing VM [4]. Patients with VM often have a significant past history of adverse experiences. This can include a mental health disorder (anxiety in 70%, depression in 40%) [22], as well as adverse experiences associated with migraine and disorders causing nausea and/or dizziness (Figure 1).

Symptoms

The diagnosis of VM relies on the clinical history. Frequently, patients presenting with vertigo do not volunteer a history of migraine, so it is important to specifically enquire about this.

The duration of vertigo varies widely from seconds to days, with further episodes occurring after days, months or less commonly, years. Nausea and imbalance are frequent associated features. Vertigo may occur as a prodromal aura before a migraine headache occur with the migraine headache or independently. Most episodes have no temporal relationship with the headaches. Susceptibility to motion sickness has found to be enhanced in patients with VM [23] and particular attention should be given to a pre-existing history of motion sickness such as being unable to read in the passenger seat of a car due to nausea [24]. Another prominent feature of VM is visually induced dizziness, where challenging visual inputs (i.e., moving images, shopping aisles) can provoke vertigo or spatial disorientation [25]. Positional vertigo can occur with VM and has been reported in 24% of patients, in contrast to 67% of patients describing spontaneous (non-positional) episodic vertigo [26]. Head motion-induced dizziness has been described as a unique feature of VM [22] but is seen in patients with unilateral and bilateral vestibulopathies also. Persistent, almost constant dizziness has been reported in 51.1% of patients with VM [22], but such patients have more likely transitioned into persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD) – a functional neurological disorder characterised by persistent non-vertiginous dizziness and/or unsteadiness [27].

Audiological symptoms are commonly reported by patients with VM and can include otalgia, tinnitus, aural fullness or pressure and subjective hearing change in more than two-thirds of patients [28]. Hyperacusis [29], and fluctuating hearing loss has also been described [30].

Additional clinical history should include any migraine-specific precipitants of vertigo attacks including menstrual cycle, sleep disturbance, emotional stress, sensory stimuli (e.g. bright lights, intense smells and noise) [31].

Signs

Clinical examination in patients with VM is typically normal, particularly in the inter-ictal phase. Non-specific, non-localising oculomotor deficits have been described in VM inter-ictally, such as smooth pursuit deficits in 48% of patients, spontaneous nystagmus in 10% of patients, and central positional or gaze-evoked nystagmus in 28% of patients [32]. When present, these abnormalities are typically subtle and other central disorders should be excluded when these findings are identified. During an acute episode, spontaneous and positional nystagmus has been recorded in 70% of patients, as well as unsteadiness during the symptomatic period [33]. VM and BPPV can co-occur in the same individual, and VM can mimic BPPV where there may be recurrent episodes of positional nystagmus and vertigo that tend not to resolve with repositioning manoeuvres [34].

Investigations

There is no specific diagnostic test for VM. Vestibular function tests have shown a range of mild abnormalities but there are no consistent trends observed. Mild sensorineural hearing loss has been described especially affecting the lower frequencies, but in such cases Ménière’s disease should be strongly suspected. Central auditory processing deficits are reported in VM with prolonged latencies on auditory brainstem response testing [35], but such findings are not specific for VM.

Management

Management of VM is based on recognised approaches for migraine. A dizziness diary can be useful in assessing an individual’s response to treatment and guide the timing of preventative therapies.

Treatment for acute episode

There is no evidence-based approach for acute treatment of VM, although many specialists will advocate the use of antiemetic medication, particularly for the treatment of accompanying nausea or vomiting. Contrary to migraine, there is inconclusive evidence for triptan use in VM. Zolmitriptan has been shown to have some benefit in a small pilot randomised placebo-controlled trial [36] and Rizatriptan reduces vestibular-induced motion sickness in patients with VM [37]. Where there is an unremitting, prolonged, distressing episode of VM, treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone has been found to be effective [38].

Prophylactic treatments

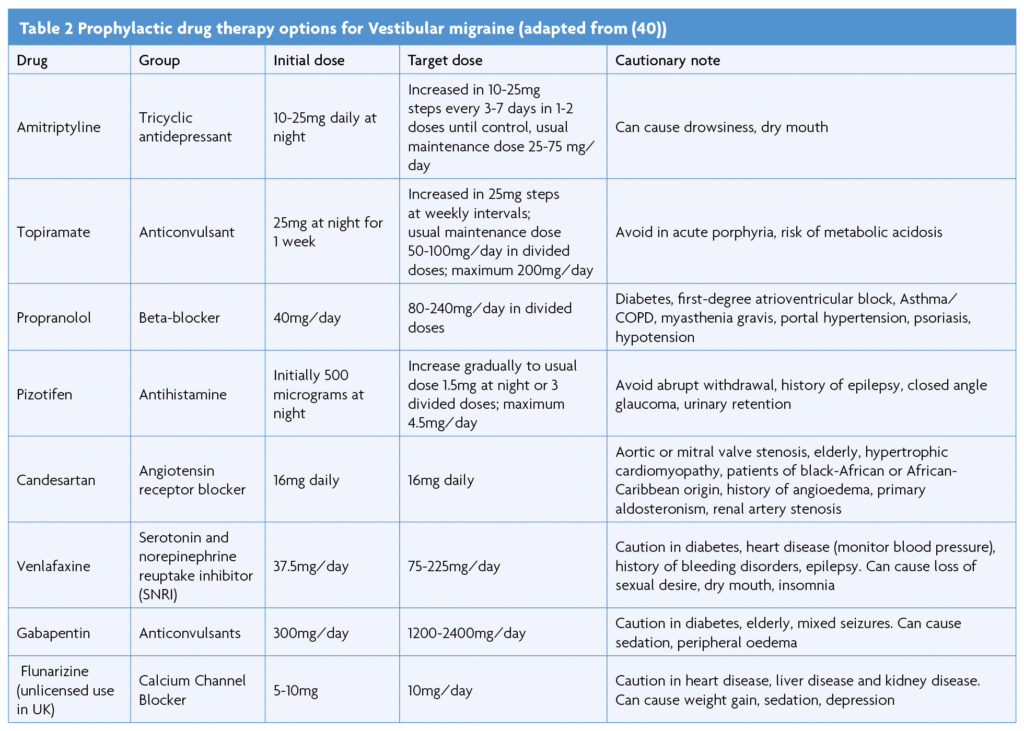

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the efficacy of preventative treatments for VM identified that antiepileptic drugs, calcium channel blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, beta-blockers, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, as well as vestibular rehabilitation demonstrated improvements in outcome parameters [39]. However, due to significant heterogeneity of studies and lack of standardised reporting outcomes a preferred treatment modality could not be determined. A similar conclusion was reached by another prospective multicentre study evaluating acetazolamide, amitriptyline, flunarizine, propranolol or topiramate for VM, finding all similarly reduced symptom severity and frequency [40].

A prospective randomised non-placebo-controlled trial suggested flunarizine is effective in reducing the severity and frequency of vertigo attacks in VM patients [41], with positive patient experiences [42]. Another prospective randomised trial compared the effectiveness of venlafaxine and propranolol in VM patients and found both were effective treating vertiginous symptoms, however venlafaxine was better at controlling depressive symptoms [43], as also shown in another study [44].

Dietary modification with reduction in migraine triggers may be beneficial, and lifestyle modification should be considered where other triggers such as stress and irregular sleep pattern may be contributory. Regular exercise can reduce stress and improve sleep [30] and reduce the intensity and frequency of VM [45]. Given that up to 65% of patients with VM may exhibit anxiety disorder [46] there may also be a role for cognitive behavioural therapy in these patients.

Vestibular rehabilitation is a useful non-medicinal pharmacological approach to treating VM, with a review reporting significant improvement in all outcomes measures, including headaches [47], although good quality randomised controlled trials are lacking.

Conclusion

Vestibular migraine is a common balance disorder with likely genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors contributing to its development. Diagnosis can be challenging due to symptom overlap with other disorders and lack of a specific diagnostic test. A thorough history and examination is essential together with relevant investigations to rule out other neurological or otological disorders. There is growing evidence that the shared pathophysiology involves central sensitisation, maladaptive neuroplasticity, thalamocortical dysrhythmia, abnormal sensory gating, and abnormal functional connectivity with dysmodulation of multimodal sensory processing. Life experiences may drive maladaptive neuroplasticity of large-scale networks involved in sensory, attention and emotion processing.

References

- Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, Waterston J, Seemungal B, Carey J, et al. Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res. 2012;22(4):167-72. https://doi.org/10.3233/VES-2012-0453

- Geser R, Straumann D. Referral and final diagnoses of patients assessed in an academic vertigo center. Front Neurol. 2012;3:169. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2012.00169

- Neuhauser HK. Epidemiology of vertigo. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20(1):40-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0b013e328013f432

- Formeister EJ, Rizk HG, Kohn MA, Sharon JD. The Epidemiology of Vestibular Migraine: A Population-based Survey Study. Otol Neurotol. 2018;39(8):1037-44. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000001900

- Cho SJ, Kim BK, Kim BS, Kim JM, Kim SK, Moon HS, et al. Vestibular migraine in multicenter neurology clinics according to the appendix criteria in the third beta edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia. 2016;36(5):454-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102415597890

- Yollu U, Uluduz DU, Yilmaz M, Yener HM, Akil F, Kuzu B, et al. Vestibular migraine screening in a migraine-diagnosed patient population, and assessment of vestibulocochlear function. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017;42(2):225-33. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.12699

- Power L, Shute W, McOwan B, Murray K, Szmulewicz D. Clinical characteristics and treatment choice in vestibular migraine. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;52:50-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2018.02.020

- Lempert T, Neuhauser H. Epidemiology of vertigo, migraine and vestibular migraine. J Neurol. 2009;256(3):333-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-009-0149-2

- Abu-Arafeh I, Russell G. Paroxysmal vertigo as a migraine equivalent in children: a population-based study. Cephalalgia. 1995;15(1):22-5; discussion 4. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.1501022.x

- Akerman S, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ. Diencephalic and brainstem mechanisms in migraine. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(10):570-84. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3057

- Bernstein C, Burstein R. Sensitization of the trigeminovascular pathway: perspective and implications to migraine pathophysiology. J Clin Neurol. 2012;8(2):89-99. https://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2012.8.2.89

- Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, Hoffmann J, Schankin C, Akerman S. Pathophysiology of Migraine: A Disorder of Sensory Processing. Physiol Rev. 2017;97(2):553-622. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00034.2015

- de Tommaso M, Ambrosini A, Brighina F, Coppola G, Perrotta A, Pierelli F, et al. Altered processing of sensory stimuli in patients with migraine. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(3):144-55. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.14

- Espinosa-Sanchez JM, Lopez-Escamez JA. New insights into pathophysiology of vestibular migraine. Front Neurol. 2015;6:12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2015.00012

- Russo A, Marcelli V, Esposito F, Corvino V, Marcuccio L, Giannone A, et al. Abnormal thalamic function in patients with vestibular migraine. Neurology. 2014;82(23):2120-6. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000496

- Brennan KC, Pietrobon D. A Systems Neuroscience Approach to Migraine. Neuron. 2018;97(5):1004-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.029

- Vecsei L, Tuka B, Tajti J. Role of PACAP in migraine headaches. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 3):650-1. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awu014

- Flook M, Frejo L, Gallego-Martinez A, Martin-Sanz E, Rossi-Izquierdo M, Amor-Dorado JC, et al. Differential Proinflammatory Signature in Vestibular Migraine and Meniere Disease. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01229

- Paz-Tamayo A, Perez-Carpena P, Lopez-Escamez JA. Systematic Review of Prevalence Studies and Familial Aggregation in Vestibular Migraine. Front Genet. 2020;11:954. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.00954

- Kelman L. The triggers or precipitants of the acute migraine attack. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(5):394-402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01303.x

- Fukui PT, Goncalves TR, Strabelli CG, Lucchino NM, Matos FC, Santos JP, et al. Trigger factors in migraine patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008;66(3A):494-9. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0004-282X2008000400011

- Beh SC, Masrour S, Smith SV, Friedman DI. The Spectrum of Vestibular Migraine: Clinical Features, Triggers, and Examination Findings. Headache. 2019;59(5):727-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13484

- Murdin L, Chamberlain F, Cheema S, Arshad Q, Gresty MA, Golding JF, et al. Motion sickness in migraine and vestibular disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(5):585-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2014-308331

- Kaski D. Neurological update: dizziness. J Neurol. 2020;267(6):1864-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09748-w

- Cass SP, Furman JM, Ankerstjerne K, Balaban C, Yetiser S, Aydogan B. Migraine-related vestibulopathy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106(3):182-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348949710600302

- Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern M, Feldmann M, Lezius F, Ziese T, et al. Migrainous vertigo: prevalence and impact on quality of life. Neurology. 2006;67(6):1028-33. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000237539.09942.06

- Popkirov S, Staab JP, Stone J. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): a common, characteristic and treatable cause of chronic dizziness. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(1):5-13. https://doi.org/10.1136/practneurol-2017-001809

- Beh SC. Vestibular Migraine: How to Sort it Out and What to Do About it. J Neuroophthalmol. 2019;39(2):208-19. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNO.0000000000000791

- Takeuti AA, Favero ML, Zaia EH, Gananca FF. Auditory brainstem function in women with vestibular migraine: a controlled study. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1368-5

- Johnson GD. Medical management of migraine-related dizziness and vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(1 Pt 2):1-28. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-199801001-00001

- Lempert T, von Brevern M. Vestibular Migraine. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(4):695-706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2019.06.003

- Zaleski-King A, Monfared A. Vestibular Migraine and Its Comorbidities. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2021;54(5):949-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2021.05.014

- von Brevern M, Zeise D, Neuhauser H, Clarke AH, Lempert T. Acute migrainous vertigo: clinical and oculographic findings. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 2):365-74. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh351

- Mahrous MM. Vestibular migraine and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, close presentation dilemma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020;140(9):741-4. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2020.1770857

- Xue J, Ma X, Lin Y, Shan H, Yu L. Audiological Findings in Patients with Vestibular Migraine and Migraine: History of Migraine May Be a Cause of Low-Tone Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Audiol Neurootol. 2020;25(4):209-14. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506147

- Neuhauser H, Radtke A, von Brevern M, Lempert T. Zolmitriptan for treatment of migrainous vertigo: a pilot randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2003;60(5):882-3. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000049476.40047.A3

- Furman JM, Marcus DA, Balaban CD. Rizatriptan reduces vestibular-induced motion sickness in migraineurs. J Headache Pain. 2011;12(1):81-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-010-0250-z

- Prakash S, Shah ND. Migrainous vertigo responsive to intravenous methylprednisolone: case reports. Headache. 2009;49(8):1235-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01474.x

- Byun YJ, Levy DA, Nguyen SA, Brennan E, Rizk HG. Treatment of Vestibular Migraine: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(1):186-94. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28546

- Dominguez-Duran E, Montilla-Ibanez MA, Alvarez-Morujo de Sande MG, Domenech-Vadillo E, Becares-Martinez C, Gonzalez-Aguado R, et al. Analysis of the effectiveness of the prophylaxis of vestibular migraine depending on the diagnostic category and the prescribed drug. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(4):1013-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-05802-5

- Lepcha A, Amalanathan S, Augustine AM, Tyagi AK, Balraj A. Flunarizine in the prophylaxis of migrainous vertigo: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271(11):2931-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-013-2786-4

- Rashid SMU, Sumaria S, Koohi N, Arshad Q, Kaski D. Patient Experience of Flunarizine for Vestibular Migraine: Single Centre Observational Study. Brain Sciences. 2022;12(4):415. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12040415

- Salviz M, Yuce T, Acar H, Karatas A, Acikalin RM. Propranolol and venlafaxine for vestibular migraine prophylaxis: A randomized controlled trial. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(1):169-74. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25445

- Liu F, Ma T, Che X, Wang Q, Yu S. The Efficacy of Venlafaxine, Flunarizine, and Valproic Acid in the Prophylaxis of Vestibular Migraine. Front Neurol. 2017;8:524. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00524

- Lee YY, Yang YP, Huang PI, Li WC, Huang MC, Kao CL, et al. Exercise suppresses COX-2 pro-inflammatory pathway in vestibular migraine. Brain Res Bull. 2015;116:98-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2015.06.005

- Eckhardt-Henn A, Best C, Bense S, Breuer P, Diener G, Tschan R, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in different organic vertigo syndromes. J Neurol. 2008;255(3):420-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-008-0697-x

- Wrisley DM, Whitney SL, Furman JM. Vestibular rehabilitation outcomes in patients with a history of migraine. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23(4):483-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00129492-200207000-00016

Endnotes

1 the sensation of self-motion when no self-motion is occurring or the sensation of distorted self-motion during an otherwise normal head movement.

2 the sensation of disturbed or impaired spatial orientation without a false or distorted sense of motion.