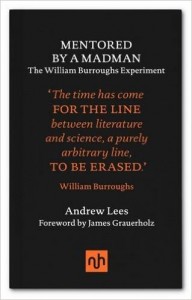

One of the most distinguished British Neurologists of the last 40 years is Andrew Lees, who is recognised as being a world authority on Parkinson’s disease with a publication record to match. Andrew is also well known for the slightly different way he has of seeing the world of research and clinical practice and in his latest book this is revealed in a new, entertaining and apposite way. In this new book Andrew discusses the influences that the late William Burroughs (a well known drug addict that wrote extensively about this in his many books, essays and articles) had on his career. In particular on his quest to find the treatment that would ultimately free patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) from many of their problems and/or complications of their oral dopaminergic treatments. The book therefore interweaves stories and episodes from Andrew’s scientific career with advice from Burroughs, and as such makes for a fascinating read.

First and foremost what comes out of this book is Andrew’s pioneering spirit. This involved him trying out therapies on himself first – selegiline to see if it truly did not evoke a cheese reaction with tyramine stimulation. This led to him being amongst the first to trial MAO-A inhibitors for PD which also led to him establishing the UK PD study group. In addition, he undertook the very first work on apomorphine in PD which began with him trying it in the privacy of his own home having had it specially made at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London. An injection that produced some interesting effects! This work followed on from his research that began in the 1970s on dopamine agonists. All of these treatments he saw through from anecdotal open label studies to mainline therapeutic interventions with an inventiveness and tenacity that is sadly hard to find in the modern day landscape of regulatory oversight. Indeed this is one of the major issues explored in this short book – namely has the research landscape changed for the better with the development of more rigorous review and regulation? He thinks not, as many breakthroughs in medicine come about by careful observation and serendipity, and then judicious experimentation. Andrew has been a great exponent of all this, often observing and noting much that goes unnoticed by others while also looking to find new empirical approaches to treatment that owe as much to intuition and reasoning – a reasoning that does not necessarily come from dry scientific articles, but the writings of others such as William Burroughs.

Overall this is a delightfully refreshing book that shows just how much Andrew has brought to this field over his career – therapies that he has championed and which we take for granted without knowing how they came to be tried in the first place. Side effects that we now all know about but which he first noticed and helped define – most notably the abnormal behaviours with dopamine agonists that he first observed with the initial patients he treated with bromocriptine in 1976! This corpus of work which he has delivered over the years has helped many careers and many patients, and in this new book the inspiration for it is laid bare. In particular this book shows that the way to do pioneering clinical research relies critically on mentors with imagination and the writings of those who may not immediately spring to the standard neurologist’s mind. So when you are next pondering what to do with your research career, read this book and consider carefully where to look for your inspiration!